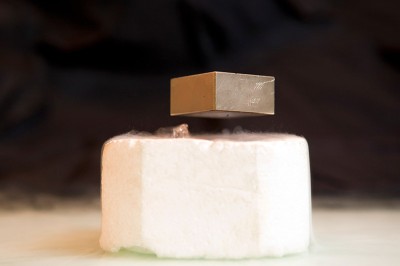

Pure crystals of LK-99, synthesized by a team at the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research in Stuttgart, Germany.Credit: Pascal Puphal

Researchers seem to have solved the puzzle of LK-99. Scientific detective work has unearthed evidence that the material is not a superconductor, and clarified its actual properties.

The conclusion dashes hopes that LK-99 — a compound of copper, lead, phosphorus and oxygen — would prove to be the first superconductor that works at room temperature and ambient pressure. Instead, studies have shown that impurities in the material — in particular, copper sulfide — were responsible for sharp drops in its electrical resistivity and a display of partial levitation over a magnet, properties similar to those exhibited by superconductors.

“I think things are pretty decisively settled at this point,” says Inna Vishik, a condensed-matter experimentalist at the University of California, Davis.

Claimed superconductor LK-99 is an online sensation — but replication efforts fall short

The LK-99 saga began in late July, when a team led by Sukbae Lee and Ji-Hoon Kim at the Quantum Energy Research Centre, a start-up firm in Seoul, published preprints1,2 claiming that LK-99 is a superconductor at normal pressure, and at temperatures up to at least 127 ºC (400 kelvin). All previously confirmed superconductors function only at very low temperatures and extreme pressures.

The extraordinary claim quickly grabbed the attention of the science-interested public and researchers, some of whom tried to replicate LK-99. Initial attempts did not find signs of room-temperature superconductivity, but were not conclusive. Now, after dozens of replication efforts, many specialists are confidently saying that the evidence shows LK-99 is not a room-temperature superconductor. (Lee and Kim’s team did not respond to Nature’s request for comment.)

Accumulating evidence

The South Korean team based its claim on two of LK-99’s properties: levitation above a magnet and abrupt drops in resistivity. But separate teams at Peking University3 and the Chinese Academy of Sciences4 (CAS), both in Beijing, found mundane explanations for these phenomena.

Another study5, by researchers in the United States and Europe, combined experimental and theoretical evidence to demonstrate how LK-99’s structure made superconductivity infeasible. And other experimenters synthesized and studied pure samples6 of LK-99, erasing doubts about the material’s structure and confirming that it is not a superconductor, but an insulator.

The only further confirmation would come from the South Korean team sharing its samples, says Michael Fuhrer, a physicist at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. “The burden’s on them to convince everybody else,” he says.

Perhaps the most striking evidence for LK-99’s superconductivity was a video taken by the South Korean team that showed a coin-shaped sample of silvery material wobbling over a magnet. The researchers said that the sample was levitating because of the Meissner effect — a hallmark of superconductivity in which a material expels magnetic fields. Multiple unverified videos of LK-99 levitating subsequently circulated on social media, but none of the researchers who initially tried to replicate the findings observed any levitation.

Half-baked levitation

Several red flags popped out to Derrick VanGennep, a former condensed-matter researcher at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who now works in finance but was intrigued by LK-99. In the video, one edge of the sample seemed to stick to the magnet, and it seemed delicately balanced. By contrast, superconductors that levitate over magnets can be spun and even held upside down. “None of those behaviours look like what we see in the LK-99 videos,” VanGennep says.

He thought LK-99’s properties were more likely to be the result of ferromagnetism. So he constructed a pellet of compressed graphite shavings with iron filings glued to it. A video made by VanGennep shows that his disc — made of non-superconducting, ferromagnetic materials — mimicked LK-99’s behaviour.

On 7 August, the Peking University team reported3 that this “half-levitation” appeared in its own LK-99 samples because of ferromagnetism. “It’s exactly like an iron-filing experiment,” says team member Yuan Li, a condensed-matter physicist. The pellet experiences a lifting force, but it’s not enough for it to levitate — only for it to balance on one end.

Li and his colleagues measured their sample’s resistivity, and found no sign of superconductivity. But they couldn’t explain the sharp resistivity drop seen by the South Korean team.

Impure samples

The South Korean authors noted one particular temperature at which LK-99 showed a tenfold drop in resistivity, from about 0.02 ohm-centimetres to 0.002 Ω cm. “They were very precise about it: 104.8 ºC,” says Prashant Jain, a chemist at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. “I was like, wait a minute, I know this temperature.”

The reaction that synthesizes LK-99 uses an unbalanced recipe. For every one part that it makes of copper-doped lead phosphate crystal — pure LK-99 — it produces 17 parts copper and 5 parts sulfur. These leftovers lead to numerous impurities — especially copper sulfide (Cu2S), which the South Korean team reported finding in its sample.

Jain, a copper-sulfide specialist, remembered 104 ºC as the temperature at which Cu2S undergoes a phase transition. Below that temperature, the resistivity of air-exposed Cu2S drops dramatically — a signal almost identical to LK-99’s purported superconducting phase transition. “I was almost in disbelief that they missed it,” says Jain, who published a preprint7 on the important confounding effect.

On 8 August, the CAS team reported4 on the effects of Cu2S impurities in LK-99. “Different contents of Cu2S can be synthesized using different processes,” says team member Jianlin Luo, a CAS physicist. The researchers tested two samples — the first heated in a vacuum, which resulted in 5% Cu2S content, and the second in air, which gave 70% Cu2S content.

The first sample’s resistivity increased smoothly as it cooled, as did samples from other replication attempts. But the second sample’s resistivity plunged near 112 ºC (385 K) — closely matching the South Korean team’s observations.

“That was the moment where I said, ‘Well, obviously, that’s what made them think this was a superconductor,’” says Fuhrer. “The nail in the coffin was this copper sulfide thing.”

Making conclusive statements about LK-99’s properties is difficult, because the material is unpredictable and samples contain varying impurities. “Even from our own growth, different batches will be slightly different,” says Li. But he argues that samples that are close enough to the original are sufficient for checking whether LK-99 is a superconductor in ambient conditions.

Crystal clear

With strong explanations for the resistivity drop and the half-levitation, many in the community were convinced that LK-99 was not a room-temperature superconductor. But mysteries lingered — namely, what were the material’s actual properties?

Initial theoretical attempts using an approach called density functional theory (DFT) to predict LK-99’s structure had hinted at interesting electronic signatures known as flat bands. These are areas where the electrons move slowly and can be strongly correlated. In some cases, this behaviour leads to superconductivity. But these calculations were based on unverified assumptions about LK-99’s structure.

To better understand the material, the US–European group5 performed precision X-ray imaging of its samples to calculate LK-99’s structure. Crucially, the imaging allowed the team to make rigorous calculations that clarified the situation of the flat bands, showing that they were not conducive to superconductivity. Instead, the flat bands in LK-99 came from strongly localized electrons, which cannot ‘hop’ in the way that a superconductor requires.

On 14 August, a separate team at the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research in Stuttgart, Germany, reported6 synthesizing pure, single crystals of LK-99. Unlike previous synthesis attempts, which had relied on crucibles, this one used a technique called floating-zone crystal growth. This enabled the researchers to avoid introducing sulfur into the reaction, thereby eliminating the Cu2S impurities.

The result was a transparent purple crystal — pure LK-99, or Pb8.8Cu1.2P6O25. Separated from impurities, LK-99 is not a superconductor, but an insulator with a resistance in the millions of ohms — too high for a standard conductivity test to be run. It shows minor ferromagnetism and diamagnetism, but not enough for even partial levitation. “We therefore rule out the presence of superconductivity,” the team concluded.

The team suggests that the hints of superconductivity seen in LK-99 were caused by Cu2S impurities, which are absent from their crystal. “This story is exactly showing why we need single crystals,” says Pascal Puphal, a specialist in crystal growth and the Max Planck physicist who led the study. “When we have single crystals, we can clearly study the intrinsic properties of a system.”

Lessons learnt

Many researchers are reflecting on what they’ve learnt from the summer’s superconductivity sensation.

For Leslie Schoop, a solid-state chemist at Princeton University in New Jersey, who co-authored the flat-bands study, the lesson about premature calculations is clear. “Even before LK-99, I have been giving talks about how you need to be careful with DFT, and now I have the best story ever for my next summer school,” she says.

Jain points to the importance of old, often overlooked data — the crucial measurements that he relied on for the resistivity of Cu2S were published in 1951.

Although some commentators have pointed to the LK-99 saga as a model for reproducibility in science, others say that it involved an unusually swift resolution of a high-profile puzzle. “Often these things die this very slow death, where it’s just the rumours and nobody can reproduce it,” says Fuhrer.

When copper oxide superconductors were discovered in 1986, researchers leapt to probe their properties. But nearly four decades later, there is still debate over the materials’ superconducting mechanism, says Vishik. Efforts to explain LK-99 came readily. “The detective work that wraps up all of the pieces of the original observation — I think that’s really fantastic,” she says. “And it’s relatively rare.”

Claimed superconductor LK-99 is an online sensation — but replication efforts fall short

Claimed superconductor LK-99 is an online sensation — but replication efforts fall short

Surprise graphene discovery could unlock secrets of superconductivity

Surprise graphene discovery could unlock secrets of superconductivity