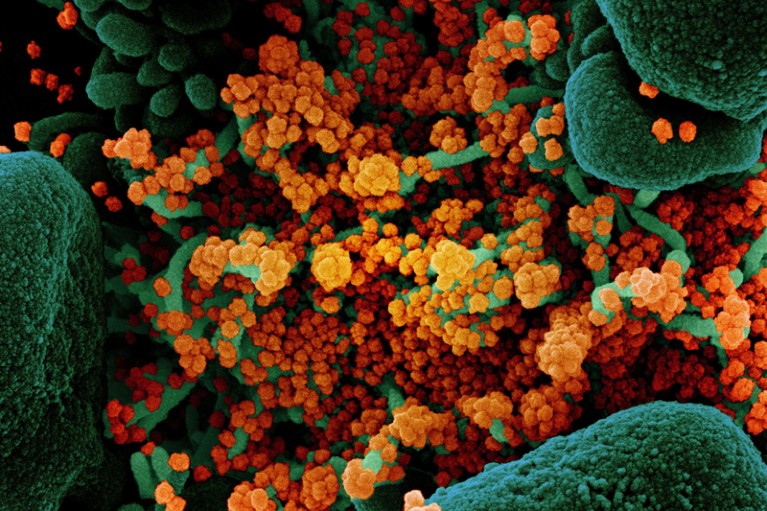

A virus is born: scanning electron micrograph of a dying cell (green) heavily infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus particles (orange), isolated from a patient sample.Credit: NIAID (CC BY 4.0)

Editorials represent Nature’s collective voice on the week’s news, providing a commentary on a range of topics, from research discoveries to major world events involving science. And although 2020 has been dominated by just one topic, we’ve aimed to stay on top of other important developments, too.

January: environmental ‘super-year’ ahead

Nature’s first editorial of 2020 marked the beginning of what was expected to be a super-year for the environment and sustainable development, with world leaders poised to meet to update their commitments in these areas. Most of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which were established by the United Nations in 2015, were not on track even before the coronavirus pandemic, and global targets to tackle climate change and reduce biodiversity loss were also behind schedule. We urged nations to consider mandatory reporting of their progress towards the SDGs, as most do for economic data. Research published in Nature from a joint US–China team provided the outlines for such a reporting framework1.

Nature’s 10: ten people who helped shape science in 2020

Throughout the year, Nature continued to publish research and commentary on the SDGs. This included a landmark study showing that, although almost 90% of children are expected to be completing primary school by 2030, only 61% of young adults will be finishing secondary education2. We also called for the global development goals to be decoupled from economic growth targets. And we marked the launch of Nature Food with a tribute to the late Donella Meadows, one of the early pioneers of the thinking that led to the SDGs .

February: stop the virus

Nature’s first editorial on the coronavirus appeared on 21 January. By the first week of February, more than 400 people had died and worldwide case numbers had reached 20,000. In two papers in Nature, teams led by researchers in China — one group at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, the other at Fudan University in Shanghai — confirmed that the virus is similar to the one that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and reported evidence that it originated in bats. The Wuhan team analysed virus samples from a small number of people, most of whom had worked at the animal market where the first cases were reported to have come from3. The Fudan team sequenced a sample from one infected market worker4.

Nature and its publisher, Springer Nature, signed a joint statement with other publishers, funders and scientific societies to ensure the rapid sharing of research data and findings relevant to the coronavirus. And we called for international donors to prioritize funding for the least developed countries as nations prepared to tackle the virus.

March: locusts and lockdowns

While all eyes were on the coronavirus outbreak, an under-reported emergency was threatening food, health and jobs in a swathe of countries. Crops in East Africa, the Middle East and south Asia had been devoured by vast swarms of the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria. A potential food crisis loomed for some 20 million people, and we backed a UN appeal for US$138 million in urgent funding — some of which was earmarked to lease aircraft that could drop chemicals to curb the insects’ spread. Later in the year, research helped to illuminate how locusts are able to congregate in swarms so quickly5.

In Kenya, a farmer’s daughter tries to chase swarms of desert locusts away from crops. This year’s crisis has been the worse some regions have seen in 70 years.Credit: Ben Curtis/AP/Shutterstock

On 11 March, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, to be a pandemic. By that point, the virus had reached more than 100 countries and infected some 120,000 people. More than 4,000 had died. Italy had declared a nationwide lockdown. But, worryingly, there were few signs that world leaders were willing to cooperate in efforts to bring the virus to heel. The United States and many European countries were not following the WHO’s advice to aggressively test, track and isolate as many cases of COVID-19 as possible. Moreover, the administration of US President Donald Trump had chosen to sideline the nation’s public-health agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, seeking instead to centralize its pandemic response.

Nature urged government science advisers around the world to publish the evidence on which policy decisions were being based, so that data could be scrutinized and policies improved — and so that all nations could defeat the virus on the basis of the best shared evidence.

April: not the time to turn against the WHO

As the virus continued on its destructive path, it became clear that the pandemic was also fuelling racism and discrimination against people of Asian descent around the world. This, we said, had to stop.

Stop the coronavirus stigma now

And, once again, Nature urged world leaders to reach out and cooperate, as tens of thousands in the research community were doing, lending time, ideas, expertise, equipment and money to the emergency public-health effort. But such calls were dealt a hammer blow when Trump announced that the United States, the WHO’s largest donor, would freeze its funding for the agency.

In early March, WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus had appealed to the world to follow the agency’s recommendations, saying, “You can’t fight a virus if you don’t know where it is. That means robust surveillance to find, isolate, test and treat every case, to break the chains of transmission.” But the Trump administration took the view that the agency had acted too slowly and was being too deferential to China — which faced questions about whether it could have acted more quickly to contain the virus, and been more transparent about the disease’s early spread.

Withholding funding from the World Health Organization is wrong and dangerous, and must be reversed

Defunding the world’s health agency amid the biggest global health crisis in a century was unthinkable, we said, and not straightforward to implement. It would be especially dangerous for those low-income countries in which the agency’s work is crucial to maintaining standards of public-health infrastructure and tackling killer diseases.

May: misinformation and vaccine hesitancy

The month coincided with an expansion of misleading claims about COVID-19. The misinformation and disinformation, most of which was circulating online, concerned subjects ranging from unproven treatments to scepticism about the safety of the vaccines being developed against COVID-19 because of the speed at which this research and development was moving. Among other things, Nature urged transparency. We recommended that researchers and companies involved in vaccine development explain what is and isn’t known about the virus, and how vaccines are made and work, and warned against over-promising or overselling their products.

June: Black Lives Matter

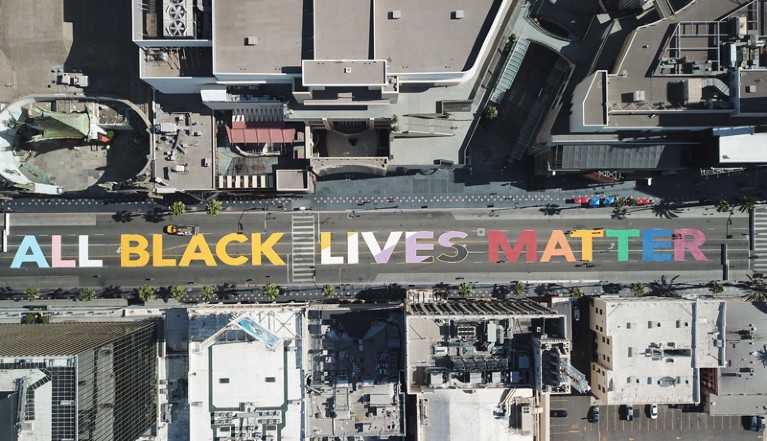

The killing of Black people in the United States, most notably that of George Floyd at the hands of the Minneapolis Police Department in Minnesota in late May, and Trump’s crushing of subsequent protests, angered the world. On 10 June, Nature joined #ShutDownSTEM #ShutDownAcademia #Strike4BlackLives, an initiative of STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) academics and organizations pausing their normal daily activities to focus on ways to eliminate anti-Black racism.

Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles, California, ahead of a march between the LGBTQ+ and Black Lives Matter communities in June.Credit: Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty

We acknowledged that Nature is among the institutions responsible for the racial bias that exists in research and scholarship, and that we must do more to correct those injustices, amplify marginalized voices, and be held accountable for these actions. We also committed to producing a special issue of the journal, working with guest editors, to explore systemic racism in research, research policy and publishing, and the part Nature has played in that.

COVID and 2020: An extraordinary year for science

One example of such embedded inequities is the story of Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman who died of an aggressive cervical cancer in the United States in 1951. While diagnosing and treating Lacks, doctors took samples of her tumour without her knowledge or consent. When these cells, which were named HeLa, were cultured in the laboratory, they exhibited an extraordinary capacity to survive and reproduce, and they are now widely used in the biological sciences.

In an editorial commemorating the centenary of Lacks’s birth, we urged the relevant authorities to put stronger rules in place to govern the use of these precious specimens. And we called for consent to be obtained from anyone who has had biological specimens taken before the samples are used in research.

The Lacks family was also keen for people to know about Lacks as a person. To Alfred Lacks Carter, one of her grandsons, the most important thing about HeLa cells is the contributions they have made to cancer research. “They were taken in a bad way but they are doing good for the world,” he told Nature.

July: mitochondria and missions to Mars

As funding agencies reassessed their priorities, a Nature paper gave a much-needed boost to the value of foundational research. Researchers at the University of Washington in Seattle and their colleagues detailed their use of an exceptional enzyme to edit the genomes of energy-generating cell structures called mitochondria6. That the team had embarked on the work with an entirely different goal in mind added to the significance of the achievement.

And, amid the coronavirus pandemic and raging geopolitical tensions, three long-planned Mars missions finally got off the ground. The latest US rover, and orbiters designed by China and the United Arab Emirates — the first Arab nation to launch an interplanetary mission — offered a powerful symbol of how efforts to explore other worlds give nations the opportunity to transcend their Earthly woes, we wrote.

August: an anti-nuclear dawn

August marks an inauspicious anniversary for science, that of the first — and, so far, only — deployment of nuclear weapons in war. But 75 years on from the bombing of Japan on 6 and 9 August 1945, a new international treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons was on the table (this is set to become international law in January 2021). The treaty’s architects, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, urged more scientists to play a part in helping it to succeed — a call that Nature supported.

Researchers: help free the world of nuclear weapons

A formal scientific advisory mechanism is yet to be established for the treaty, so setting up a global network of researchers with knowledge of various aspects of nuclear science and technology is an urgent outstanding task. The world’s nuclear arsenal is alarmingly large, comprising an estimated 1,335 tonnes of highly enriched uranium and 13,410 warheads. Some 90% of these are in the United States and Russia.

September: postdocs in crisis

Nature’s first-ever survey of postdoctoral researchers showed the extent to which the pandemic is hurting science’s workforce. Half of the 7,670 respondents — a self-selecting sample, based mostly in Europe and North America, and covering 19 disciplines — revealed that they were considering leaving academic research because of work-related mental-health concerns. Funders responded to coronavirus-related laboratory shutdowns by extending research-project deadlines, but there were few offers of extra funding.

Postdocs in crisis: science cannot risk losing the next generation

In two editorials, Nature called for postdocs to be funded through deadline extensions, because many have no other source of income. Some funders said that universities could step in to support postdocs — despite the fact that institutions in many countries are not being given additional funds to deal with the pandemic. It spells trouble for knowledge, discovery and invention if so many people are concluding that they have no future in academic research.

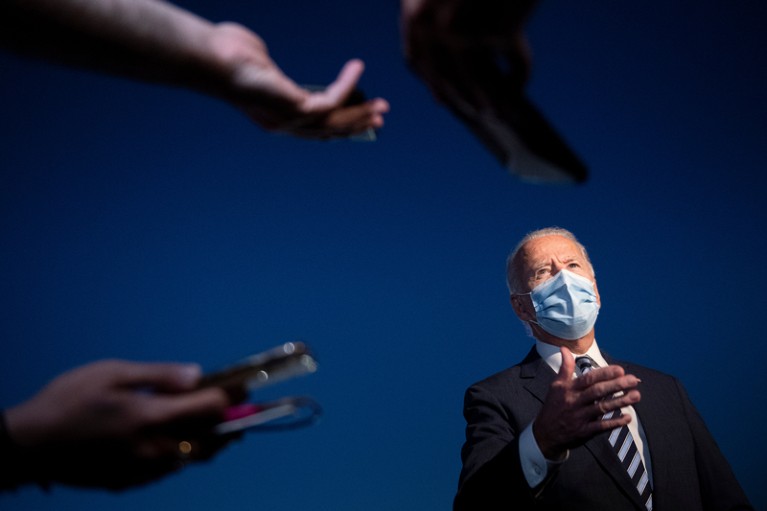

October: it has to be Biden

“We cannot stand by and let science be undermined. Joe Biden’s trust in truth, evidence, science and democracy make him the only choice in the US election.” So began Nature’s editorial less than three weeks before the presidential election of 3 November. Nature, along with colleagues across science and research publishing, endorsed Biden. Since the election, we have urged the incoming administration to follow through on Biden’s promises to restore science and evidence to policymaking, starting with rebuilding the Environmental Protection Agency.

US presidential candidate Joe Biden talking to reporters in October, ahead of the November election.Credit: Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty

Following the Trump administration’s relentless and high-profile attacks on science — and the politicization of the pandemic and threats to scholarly autonomy around the world — the journal pledged to cover more politics news, commentary and primary research.

November: the ethics of facial recognition

Nature reported, in a series of Features, the increasing concerns of researchers in the field of facial-recognition technology about how the technology is being used, for example by governments and law-enforcement agencies. Some researchers, as our editorial highlighted, are rightly joining campaigners in calling for greater regulation and transparency, as well as for communities that are being monitored by cameras to be consulted — and for use of the technology to be suspended until lawmakers have reconsidered where and how it should be used. There might well be benefits to the technology, but these must be assessed against the risks, making proper regulation essential, we argued.

December: vaccines are coming

COVID-19 vaccine roll-outs began in the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States after the first emergency-use authorizations were granted in these countries. Vaccines are in use in Russia and China, too — and China is also supplying other countries. But global coordination is still lacking, with countries conducting approvals according to different criteria, and with the wealthiest procuring the majority of early orders.

A health worker prepares to inoculate a trial volunteer with a COVID-19 vaccine produced by the Chinese company Sinopharm.Credit: Ernesto Benavides/AFP/Getty

We revived the long-standing question of how the harmonization of vaccine regulation might be accelerated. A review of the regulatory landscape established that, across 24 countries, there are at least 51 pathways to various types of accelerated vaccine approval7.

Greater harmonization offers many benefits, we argued, but would also require companies to allow the creation of — or help to create — a secure means of sharing data for regulators, many of whom are not currently permitted to do this. If regulators all had access to the same data, it would be easier for them to compare their findings and analyses with those of others. Their decisions would be more robust and that, in turn, would shore up public confidence in immunization.

One year after the first known case of coronavirus infection, this pandemic, which has killed more than 1.7 million people, could, we hope, be coming to an end at last.

Nature’s 10: ten people who helped shape science in 2020

Nature’s 10: ten people who helped shape science in 2020

COVID and 2020: An extraordinary year for science

COVID and 2020: An extraordinary year for science

2020 beyond COVID: the other science events that shaped the year

2020 beyond COVID: the other science events that shaped the year

The best science images of 2020

The best science images of 2020

Get the Sustainable Development Goals back on track

Get the Sustainable Development Goals back on track

Calling all coronavirus researchers: keep sharing, stay open

Calling all coronavirus researchers: keep sharing, stay open

A lack of locust preparedness will cost lives

A lack of locust preparedness will cost lives

Stop the coronavirus stigma now

Stop the coronavirus stigma now

Withholding funding from the World Health Organization is wrong and dangerous, and must be reversed

Withholding funding from the World Health Organization is wrong and dangerous, and must be reversed

COVID vaccine confidence requires radical transparency

COVID vaccine confidence requires radical transparency

Systemic racism: science must listen, learn and change

Systemic racism: science must listen, learn and change

How to reach another planet when a pandemic is hobbling yours

How to reach another planet when a pandemic is hobbling yours

Researchers: help free the world of nuclear weapons

Researchers: help free the world of nuclear weapons

Postdocs in crisis: science cannot risk losing the next generation

Postdocs in crisis: science cannot risk losing the next generation

Why Nature supports Joe Biden for US president

Why Nature supports Joe Biden for US president

Facial-recognition research needs an ethical reckoning

Facial-recognition research needs an ethical reckoning

COVID vaccines: the world’s medical regulators need access to open data

COVID vaccines: the world’s medical regulators need access to open data