Abstract

Fossil sloths are regarded as obligate herbivores for reasons including peculiarities of their craniodental morphology and that all living sloths feed exclusively on plants. We challenge this view based on isotopic analyses of nitrogen of specific amino acids, which show that Darwin’s ground sloth Mylodon darwinii was an opportunistic omnivore. This direct evidence of omnivory in an ancient sloth requires reevaluation of the ecological structure of South American Cenozoic mammalian communities, as sloths represented a major component of these ecosystems across the past 34 Myr. Furthermore, by analyzing modern mammals with known diets, we provide a basis for reliable interpretation of nitrogen isotopes of amino acids of fossils. We argue that a widely used equation to determine trophic position is unnecessary, and that the relative isotopic values of the amino acids glutamate and phenylalanine alone permit reliable reconstructions of trophic positions of extant and extinct mammals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Home to more than half of Earth’s land biota, South America contains the highest diversity of extant terrestrial mammals of any continent1. Little is known, however, about the ecological structure of mammalian communities before the megafaunal extinctions of the last Pleistocene ice age, when more than 80% of mammals above 40 kg became extinct2. Characterizing the paleoecology of South American (SA) fossil mammals is particularly challenging, because those communities bear little resemblance to modern or fossil guilds from other continents due to marked taxonomic and phylogenetic disparities and unusually large numbers of entirely extinct clades3. Another aspect of this perceived uniqueness is the depauperate abundance and diversity of mammalian carnivores throughout the Cenozoic. Lack of placental mammalian carnivores is particularly puzzling for the Pleistocene because all large marsupials (e.g., borhyaenoids) and non-mammalian predators such as terrestrial crocodiles (i.e., sebecids) and large flightless “terror birds” (i.e., phorusrhacids), which likely maintained terrestrial food web energy transfer balances in the Tertiary, were already extinct by this epoch. Allometric functions relating population densities to body mass indicate that Pleistocene SA mammalian communities were ecologically imbalanced because the herbivore biomass markedly surpassed the energetic requirements of carnivores4. It has been further suggested that Pleistocene ecosystems could not have supported the plant biomass demands of all the presumed large herbivores, which implies that secondary consumers disguised as herbivores must exist in the fossil record but have not been recognized as such4. Because of their high taxonomic diversity and simple yet potentially functionally versatile dentitions, fossil sloths (Xenarthra, Folivora) have been identified as the most likely candidates to have occupied scavenger niches4,5. All modern sloth species, however, are obligate tropical arboreal herbivores, with extreme feeding specializations involving the exploitation of food of low nutritional quality, with the extra physiological challenges entailed by the poor digestibility of plant allelochemicals6. The traditional consensus that fossil sloths were also obligate herbivores like their modern relatives is based mostly on craniodental morphology analyses and a presumption of shared, phylogenetically conserved dietary adaptation across the group. Dental structures and jaw biomechanics of sloths, however, do not preclude the ingestion of foods that require little or no preparation, as in certain kinds of scavenging (e.g., ingestion of animal soft tissues where minimal or no chewing is involved). Furthermore, their extremely high diversity and incredibly broad range of body sizes, geographic distributions, and inferred habitats, including even a marine sloth7, suggest that some of the hundreds of known species of fossil sloths may have been much more versatile ecologically than traditionally thought. Sloths (together with other xenarthrans, such as anteaters, armadillos, and extinct close relatives) comprised a substantial proportion of South American mammalian diversity until as recently as 10,000 years ago8. Reliably determining the trophic relationships of xenarthrans is thus crucial for understanding the evolution of Neotropical mammalian biodiversity, as well as the interplay between resource availability, ecological functions among xenarthrans, and competition within and across mammalian clades in South America over the Cenozoic.

Trophic inferences using stable isotopic composition

Isotopic analyses are now widely applied in ecological and paleoecological studies. These techniques rely on two underlying premises. First, that isotopic values of any given chemical element differ across diverse reservoirs in the biosphere, yielding isotopically varied foods and waters. Second, because an organism’s body tissues are synthesized from the food and water they ingest, they are isotopically linked to those sources in a predictable way9. Stable isotope analyses therefore offer a rare route to directly document the consumed diet itself, rather than relying on indirect inferences based on morphological proxies, representing a particularly useful and potentially more reliable method to be applied to fossils. Traditionally, nitrogen stable isotope analyses (δ15N) of bulk tissue are used to evaluate trophic levels due to an empirically documented increase of 3–5‰ in δ15N values per trophic level change10,11. However, substantial variation in δ15N values has also been observed within trophic guilds11,12, indicating that the use of δ15N values alone can be a misleading proxy to identify trophic levels. Indeed, interpretation of bulk tissue δ15N values often fails to acknowledge variations in baseline δ15N values within an ecosystem13, which can greatly differ depending on the isotopically different types of inorganic nitrogen sources available for the primary producers (e.g., N2, NH3, NO−314), the way nitrogen was obtained (direct uptake of nitrogen from soil or through symbiotic microbes), and where nitrogen was assimilated by the plant (e.g., root, shoot).

In contrast, amino acid compound-specific isotope analysis (AACSIA), a more recent technique that measures and evaluates the δ15N values of specific amino acids, overcomes the issue of unknown or variable baseline δ15N values because it records both baseline (i.e., that for the overall primary producer community) and trophic information in the same organism15,16,17,18. Indeed, studies have shown that certain amino acids (AAs) experience little change in their δ15N values from ingested diet to consumer body tissues, whereas others differ significantly15. The explanation behind this observation relies on whether or not the metabolic pathways of amino acids are engaged in transamination or deamination reactions (involving the breakdown of C-N bonds) and the extent to which amino acids exchange their amino-nitrogen with the overall metabolic pool of nitrogen19. Amino acids that readily exchange their amino-nitrogen, thereby experiencing large isotopic fractionations, have been termed “trophic” amino acids, whereas those implicated in metabolic processes that involve little or no breakdown or formation of C-N bonds, and thus are similar to baseline δ15N values, are known as “source” amino acids17,19. The higher the trophic level of an organism, the more metabolic cycles their amino-nitrogen will be involved in, and therefore the difference between the δ15N values of trophic versus source amino acids will progressively increase. Among “trophic” AAs, glutamic acid (Glx, analyzed as glutamate) usually experiences a large increase in its δ15N values with each trophic level transfer20, as its central role in nitrogen metabolism of heterotrophs involves transamination reactions19,21. In contrast, among source amino acids, phenylalanine (Phe) has been observed to experience minimal increase in its δ15N values per each trophic level, as its main initial metabolic step, the formation of tyrosine, does not involve breaking C–N bonds20,21,22. Constancy of these distinct patterns between Glx and Phe across organisms makes them the two canonical “trophic” and “source” amino acids15,16,17,23. Indeed, the most popular equation 20 to calculate trophic positions (hereafter referred to as “TP Eq”) uses the δ15N values of those two amino acids, although a few studies have instead proposed a combination of multiple trophic and source amino acids to calculate trophic levels14,24,25.

Although widely applied in archaeological, anthropological, and paleontological research (e.g., to evaluate dietary practices of ancient humans and other hominoid species (e.g.,23,26), application of the AACSIA TP Eq is not without caveats, as this equation relies on constants (β value and trophic discrimination factor [TDF]) that have not been thoroughly evaluated in terrestrial ecosystems. Indeed, the equation relies on the assumption that the β value (isotopic differences between glutamate and phenylalanine [“big delta” Δ] in primary producers) and the TDF (15N-enrichment of glutamate relative to phenylalanine per trophic level change [ΔGlx − ΔPhe]) are both constant across all organisms within an ecosystem. For terrestrial ecosystems, β values of − 8.4‰ and − 0.4‰ are considered representative of C3 and C4 plant-dominated ecosystems, respectively20,27; however, a recent meta-analysis of β values, demonstrated considerably more variation than currently acknowledged28. On the other hand, a standard TDF value of 7.6‰ has been used to calculate trophic positions of all consumers, whether terrestrial or aquatic, modern or extinct, vertebrate or invertebrate, yet its assumption of constancy has only been tested on marine invertebrates, fishes, birds, insects, and heterotrophic bacteria, where it is also known to vary16,20,29,30,31. The only prior controlled experimental study we are aware of on a terrestrial mammal, Bos taurus32, showed different β (− 4.5‰) and TDF (4‰) values than those used in the TP Eq, suggesting that these “universal” values cannot be applied uniformly across food webs and ecosystems.

For these reasons, we posit that the TP Eq cannot be used to confidently calculate the trophic position of mammals (also see33). We argue instead that this equation is not necessary in any case, and that the δ15N values of glutamate (δ15NGlx) and phenylalanine (δ15NPhe) alone permit reliable determinations of trophic positions of mammals. To document this, we first tested the predictive power of this relationship in modern mammalian species under different, known feeding regimes or diets (in both controlled and wild environments), to provide a basis for reliable interpretation of δ15N AACSIA of fossil samples. We then used this proxy to test the hypothesis of carnivory and consumption of proteins of animal origin in the targeted fossil sloths, Mylodon darwinii and Nothrotheriops shastensis.

Results

δ15N of Glx and Phe

The seven xenarthran species included in this study (sloths [extant and extinct] and anteaters) display substantial intra- and inter-specific variation in their δ15NPhe values (> 15‰ across individuals, Table 1, Table S1), with the spectrum of δ15NPhe variation being bracketed by the two fossil sloth species, Mylodon darwinii (median δ15NPhe = 2.5‰) and Nothrotheriops shastensis (δ15NPhe = 17.7‰). The greatest intraspecific δ15NPhe variation (8.4‰ span) is observed in Choloepus (fed an omnivorous diet in the zoo, SI), with hair keratin δ15NPhe values ranging from 3.2 to 11.6‰. Intraspecific variation in δ15NGlx values is smaller than that for δ15NPhe, with Choloepus and Mylodon showing the greatest variation among individuals (2.5‰). Inter-specific variation in δ15NGlx spans 14‰, with the extreme values also bracketed by the fossil sloths Mylodon (median δ15NGlx = 5.6‰) and Nothrotheriops (δ15NGlx = 19.6‰).

The δ15N values of bulk dietary samples for zoo specimens are bracketed by the results for the two living sloth species, the mixed plant/animal diet of Choloepus (δ15NPhe = 4.5‰, δ15NGlx = 5.3‰) and the rubber plant Ficus elastica, Bradypus’s monospecific diet (δ15NPhe = 18.6‰, δ15NGlx = 11‰; Table S2). The offset between the δ15N values of glutamic acid and phenylalanine (β value) for Ficus elastica is − 7.6‰ (Table S3). Mixed component (“omnivorous”) zoo diets show similar offsets in their δ15NGlx-δ15NPhe values (Δ), ranging from − 1‰ for the diet of the pygmy anteater Cyclopes to 0.8‰ for that of Choloepus. The dietary Δδ15NGlx − δ15NPhe result for Myrmecophaga and Tamandua (both species fed the same diet at the zoo) was − 0.4‰ (Table S3).

Because baseline δ15NPhe and δ15NGlx values can vary across ecosystems, what is actually informative for trophic position inferences is how δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe values compare to each other in the animal under study (e.g., the absolute difference [“big delta” Δ] or as reflected in linear regression models, Fig. 1). Significant differences in the Δδ15NGlx − δ15NPhe are observed among species in distinct dietary categories (p < 0.001, Fig. 1, Table 2, Table S4, S5). The median Δδ15NGlx − δ15NPhe of herbivores is significantly lower (− 0.7‰, n = 15) than that of omnivores (4.6‰, n = 21; including zoo animals fed mixed-diets [plant/animal], t(21.9) = − 10.2, p < 0.001) and marine consumers (15.5‰, n = 17, p < 0.001) (Table 2, Table S4, S5). Among herbivores, the range of variation in Δδ15NGlx − δ15NPhe (2.7‰) is bracketed by two artiodactyls, the buffalo Syncerus caffer (− 2.3‰) and sheep Ovis aries (0.4‰, Table S6). The range of variation in Δδ15NGlx − δ15NPhe among omnivores is large (9.5‰), bracketed by humans with high plant content in their diets (1.2‰; C4 consumers sensu34) and the common genet Genetta genetta (10.7‰). The range of variation in Δδ15NGlx − δ15NPhe in marine consumers also is large (11.6‰), ranging from 12.1‰ in a population of Homo sapiens from South Africa to 23.7‰ in the fish-eating bat Myotis vivesi. The ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe values in marine consumers are significantly higher (p-value < 0.001) than for any terrestrial feeding guild (i.e., herbivores and omnivores). Data for terrestrial carnivores is limited to three species with ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe values lower than for all marine consumers: the hyena Crocuta crocuta (∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe = 11.2‰), the fringe-lipped bat Trachops cirrhosus (∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe = 10.2‰), and the spectral bat Vampyrum spectrum (∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe = 11.5‰). Fossil sloths were not placed in any dietary category a priori. The Δδ15NGlx − δ15NPhe values for Mylodon overlap those of taxa within the omnivore category (median = 2.7‰) while Nothrotheriops best fit values in the herbivore category (median = 1.9‰, Fig. 1, Table S5).

Scatter plot of δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe (A) and ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe (B) for mammals, separated by feeding ecology categories. (A) Regression lines plotted for: modern herbivores (n = 15, solid green line, R2 = 0.96, p < 0.001); modern herbivores + fossil Nothrotheriops (dashed green line, R2 = 0.96, p < 0.001); modern wild omnivores (i.e., excluding zoo anteaters, n = 18) (solid brown line, R2 = 0.28, p = 0.03), modern omnivores + both fossil sloth species (dashed brown line, R2 = 0.68, p < 0.001), modern omnivores + fossil Mylodon (while excluding the two outliers of this regression Nothrotheriops and Genetta [determined by robust regression and diagnostic analyses], dotted brown line, R2 = 0.71, p < 0.001). Grey shading is the standard error, including Mylodon with omnivores and Nothrotheriops with herbivores. Yellow lines represent theoretical trophic levels from the TP equations by20. Notice that except for primary consumers (TP = 2), the theoretical trophic levels obtained from those equations do not match the known feeding ecologies for mammals in higher trophic levels. Data used for this figure comes from this study and a thorough literature compilation (Table S6). (B) M = Mylodon, N = Nothrotheriops.

Ordinary least square (OLS) analyses of δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe for 59 mammalian species yielded strong correlations between these two AAs for herbivores (R2 = 0.96, p-value < 0.001, SE = 0.7 on 13 degrees of freedom [df]), marine consumers (R2 = 0.52, p-value = 0.002, SE = 3.6 on 13 df), and wild omnivores (R2 = 0.28, p-value = 0.03, SE = 2.3 on 16 df) (Fig. 1, Table 2, Table S5). The ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe values in modern mammals increase per trophic level change (Fig. 1, Table S5). Values for herbivores and omnivores are notably different and do not overlap (Fig. 1, Table S5), when excluding the zoo anteaters (removed because of their artificial dietary components differing markedly from their specialized insectivore diet in the wild, see SI). Analysis of covariance was used to assess the effect of dietary classification (herbivores, omnivores, and marine consumers) on the δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe interaction (i.e., statistical differences in slopes and intercepts among regression lines, with δ15NGlx modelled as the dependent variable). Our results show that there is a significant effect of diet on δ15NPhe, but no significant interaction (i.e., the slopes are not significantly different; F(1, 43) = 0.36, p = 0.78; Table S4). In contrast, diet has a significant effect on δ15NGlx, observed as differences in intercepts among the regression lines (F(3, 46) = 116.5, p < 0.01; Table S4).

Additional ordinary least square (OLS) analyses and robust regressions were carried out classifying fossil sloths either as herbivores or as omnivores, to evaluate the best dietary category fit for these species relative to known dietary correlations in extant taxa (Fig. 1). Fossil sloths were not placed a priori in any dietary category in the initial analyses that included only living taxa. When the OLS analysis was run with both fossil sloths classified as herbivores, the correlation between δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe remained strong (p < 0.001), but R2 decreased from 0.96 to 0.86. When only Nothrotheriops is considered as an herbivore, however, the correlation between δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe for herbivores is as strong (R2 = 0.96, p < 0.001) as when only modern taxa are analyzed (Fig. 1, Table S5). When both fossil sloths were classified as omnivores, the correlation between δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe for this dietary category is strong (R2 = 0.7, p < 0.001). However, results from robust regression and diagnostic analyses of fossil and extant taxa together identified Nothrotheriops (along with Genetta) as influential outliers for the omnivorous correlation (Cook’s D > 4/n). The exclusion of these two outliers, and inclusion of Mylodon as an omnivore, greatly improved the strength of the omnivore correlation (R2 = 0.71, p < 0.001, Fig. 1, Table S5).

Discussion

Our results document that we can accurately reconstruct the trophic position of mammal species from δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe values alone (both the ∆ value and correlations between the two amino acids), which are therefore preferable to relying on an equation with poorly constrained constants introducing uncertainties. Indeed, the TP Eq often failed to place captive and wild mammalian omnivores in their correct trophic positions (as was also observed in other mammalian33 and non-mammalian organisms35,36, Table S6). Misidentification of many mammalian omnivores using the TP Eq might be associated with the consumption of dietary items of mixed origin (C3, C4, marine, or a combination of those), which introduces uncertainties that are not accounted for when using single constant β and TDF factors (see discussion of predictive power of the TP Eq for mammals in SI). Low ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe values for the captive anteaters (− 2.2 and − 0.3 for Tamandua and Cyclopes respectively) are likely due to the fact that these individuals are fed diets containing protein supplements with higher δ15NPhe values than expected for secondary consumers, consequently blurring the ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe values naturally observed in other species in that trophic level. The weaker correlation between δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe for wild omnivores compared to herbivores or marine consumers is likely due to the fact that this feeding category includes mammals incorporating widely different proportions of distinct source foods (e.g., fruits/plants, invertebrates, and vertebrates) in their diets.

Based on the OLS analysis and their ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe values (Fig. 1), the two fossil sloths, Mylodon and Nothrotheriops, occupy distinct trophic positions, but in contrast to what might be interpreted from bulk δ15N values (Fig. 2, Table S7), Mylodon is in a higher trophic position than Nothrotheriops. Indeed, Mylodon better fits the omnivore linear regression and its ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe values (2.6 to 3.1) match those of modern omnivores, such as the American marten. In contrast, although the ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe value obtained for the fossil sloth Nothrotheriops (1.9) fit that of some low-meat consuming omnivores (e.g., Homo sapiens consuming C4 plant resources), it was found as an outlier in the omnivore regression and thus is conservatively interpreted as an herbivore (Table S5). There is no evidence for consumption of items of marine origin in either sloth species, which is not surprising for Nothrotheriops, mostly known from continental interior desert habitats in the southwestern U.S., but rules out potential dietary incorporation of available marine resources for Mylodon, which lived near coastal areas. The remarkably high AA and bulk δ15N values of Nothrotheriops (the δ15NPhe value is higher than any other mammal analyzed, terrestrial or marine) is likely due to the arid conditions in which this animal lived, as plant δ15N values increase with decreasing water availability37,38 and the taxonomic composition of the plants identified in its diet (from dung) consistently correspond to desert taxa still present in the area39,40.

Nitrogen isotope values of individual amino acids and bulk hair for the two fossil sloth species Mylodon darwinii and Nothrotheriops shastensis. S = source AAs, T = trophic AAs, M = metabolic AA. Variation in bulk δ15N reflect variations in hair sections as described in main text (also see Fig S1).

The offset between δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe values (i.e., β value) is significantly different in plants performing C3 (~ − 8.4‰) versus C4 (~ 0.4‰) photosynthesis20, although substantial variation also exists among C3 plants (e.g., ranging from − 2.6‰ in Urtica doica to − 12.2‰ in Sambucus nigra) depending on the degree of vascularization28 and amount of lignin produced by the plant species27. Mammalian herbivores, whether feeding on C3 or C4 resources, however, do not differ significantly in ∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe values (p-value = 0.77, SI Dataset). Thus, the almost 1:1 correlation between these two amino acids in terrestrial herbivores is independent of the type of plant consumed (Fig. 1), and therefore also independent of ecosystem. This observation gives an undeniable power to the δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe correlation to predict herbivory. This also implies that C3- and C4-consuming herbivores have disparate patterns of amino acid δ15N discrimination, with significantly large 15N enrichment in the Glx of C3 herbivores versus minimal enrichment in C4 herbivores. Data on controlled-diet zoo mammals feeding on a single plant species (e.g., the three-toed sloth Bradypus feeding on Ficus elastica [this study] and the cow Bos taurus feeding on Lolium perenne32) and data on wild mammals feeding on C3 or C4 plants (SI Dataset) both corroborate this observation.

Assessing the results of all analyses together (∆δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe and linear relationships between δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe in extant mammals) suggests that while the Shasta ground sloth Nothrotheriops shastensis was likely an obligate herbivore, Darwin’s sloth Mylodon darwinii was not, instead occupying a higher trophic position. AA δ15N values indicates that the feeding ecology of the fossil sloth Mylodon darwinii best fits within the mixed-feeder/omnivore dietary category, with a degree of meat-eating omnivory comparable to that of the extant American marten. Further, the strength of the correlation between δ15NGlx − δ15NPhe for modern herbivores, regardless of its ecosystem (specimens analyzed live in a wide array of ecosystems) or the type of vegetation consumed (C3/C4, woody/non-woody plants) makes it extremely unlikely for Mylodon to have been an obligate herbivore.

Comparison of δ15N AACSIA results to interpretations from other proxies

Macroscopic analysis and DNA sequences extracted from Nothrotheriops shastensis coprolites (from Rampart and Gypsum Caves in the US39,41), revealed a variety of plant species but no evidence for a non-herbivorous diet. Mylodon darwinii dung has been subject to ancient DNA studies aimed to explore evolutionary relationships of this species42,43, but only one study attempted to characterize its diet from dung44. This macro- and micromorphological study of dung content found Mylodon’s diet to be composed mostly of grasses and sedges, concluding that it most likely was a grazer44, in contrast to morphological interpretations45. The absence of hardly digestible material (e.g., bones) in any Mylodon’s coprolites shows that this species could not have been a strict carnivore (or a hyena-type scavenger) but does not exclude an opportunistic omnivore behavior because other animal protein-rich dietary items (e.g., meat, eggs) are rapidly assimilated after ingestion. In this case, fecal components will be biased towards plant dietary items because cellulose is difficult to digest. Indeed, macro- and micromorphological analyses of feces do not allow precise identification of an animal’s full dietary composition, as has been exhaustively demonstrated in archaeological studies of human coprolites46.

Anatomical studies on modern herbivores, on the other hand, showed a strong correlation of dental occlusal surface area (OSA) with efficiency and capacity of food processing, digestive physiology, and food quality47. Hindgut fermenting grazers, such as horses, have greater relative OSAs than do cows (ruminant foregut fermenters); by being more efficient at orally reducing the particle size of the ingested food, horses compensate for shorter digesta retention times than ruminants48. Compared to modern herbivores, fossil sloths (with the sole exception of Megatherium americanum) had smaller occlusal areas than expected for their body masses49, indicating that they had a lower capacity for food processing than do extant herbivores of similar sizes.

Of all fossil sloth species analyzed, mylodontids (the clade including Mylodon darwinii) had the lowest relative OSA values, reflecting poor oral food processing efficiency. These results were interpreted as likely due to lower energetic requirements of fossil sloths, suggesting in turn that fossil sloths might have required lower food intake than other mammals of similar sizes49. Although low basal metabolic rates might partially account for these seemingly incongruent digestive physiology inferences, there is no compelling evidence for unusually low metabolic rates in fossil sloth species. McNab50 proposed that Mylodon and Nothrotheriops would have had basal metabolic rates of 50% of that expected from their body mass. Those estimations are not convincing, however, because they were based on the length of hair strands and fur thickness, while energy transfer along hairs also depends on other traits such as hair diameter and number and arrangement of hair in the fur51. Even assuming those estimations were roughly correct, Mylodon is thought to have faced ambient temperatures well below its thermoneutrality50, and therefore it would have needed to increase its metabolism to maintain a constant body temperature in cooler conditions. Furthermore, a fact considered crucial in explaining the low metabolic rates in modern xenarthrans is their food preferences, including plant items with extremely low energy content and allelochemical defenses against herbivory50.

That fossil sloths were foregut fermenters is highly likely because extant sloths, phylogenetically bracketing almost the entire diversity of fossil sloths, are foregut fermenters6. Assuming that their digestive efficiencies were at least comparable to that of modern ruminants, however, poses a physiological and anatomical problem because Plio-Pleistocene sloths reached larger body masses than the largest extant foregut fermenter, the hippo (considered to have attained the upper body size limit for non-ruminant foregut fermenters52). Foregut fermenters tend to have smaller large intestines (namely, the colon descendens) than hindgut fermenters, which results in reduced colonic water reabsorption52. The foregut of Mylodon would have represented ~ 20%− 24% of its body weight (calculation based on the reticulorumen equation of52, assuming a body mass of 1500–2000 kg, SI) which is comparable to that observed in modern hippos. However, high water loss resulting from a reduced caecum and colon in the hippos is hypothetically overcome by their amphibious lifestyles52. An amphibious lifestyle for Mylodon, however, has never been proposed, nor would one be consistent with habitats in which they are known to have lived in. For other mylodontids, such as the giant ground sloth Lestodon (estimated weight > 4 tons), the issue of colonic water reabsorption is even more extreme because their foregut would have represented almost 40% of their total weight (even assuming that these were browsers, and not grazers as suggested by craniodental morphology studies45; calculations the same as above]).

An alternative explanation for these results on fossil sloths, and Mylodon in particular, would be ingestion of a higher quality of food. Indeed, if Mylodon was an opportunistic scavenger and incorporated, even if only sporadically, meat or other animal dietary elements, then its relatively small oral food processing capacity would be more congruent with the apparent physiological constraints imposed by its body mass and foregut fermentation strategy. The energetic requirements of Mylodon, with its need for higher metabolic rates due to air temperatures below its thermoneutrality, also are more consistent with omnivory than obligate herbivory. Our δ15N AACSIA results support this interpretation, as they clearly indicate that Mylodon was not an obligate herbivore, but instead was an omnivore showing consumption of animal proteins in proportions comparable to the American marten and other mixed feeders.

Conclusions and implications

Increased sampling and a new analytical framework for AACSIA data document the high predictive power of relationships between δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe values in modern mammals with known diets, and from distinct ecosystems, digestive physiologies, and phylogenetic relationships. These relationships indicate that analyses of δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe alone are preferable to inferences of trophic position using an equation (TP Eq) with inaccurate or poorly documented assumptions, and permit reliable reconstruction of diets in fossil taxa from terrestrial ecosystems. More δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe data on modern secondary consumers may permit differentiation of insect-eating from meat-eating omnivores, as well as from terrestrial hypercarnivores, by teasing apart patterns of interspecific variation in δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe relative to particular food sources for omnivores.

The newly established relationships between dietary category and δ15NGlx and δ15NPhe, enable us to conclude that while Nothrotheriops was likely an obligate herbivore, Mylodon was not. Our data, from direct isotopic evidence of the food consumed, clearly indicate that Mylodon was not an exclusive herbivore, as commonly presumed, but rather that its feeding behavior better fits that of an omnivore, consuming plant material but sometimes also incorporating items of animal origin in its diet. Although the craniodental and skeletal morphology of sloths does not support them being active predators, an opportunistic scavenging behavior for Mylodon would be in agreement with our results obtained via AACSIA. Our conclusions, from direct isotopic evidence of the food consumed, are also supported by studies on masticatory muscle structure reconstructions, biomechanics, and morphogeometry for Mylodon, indicating that it would have been inefficient at processing food and at a disadvantage (in terms of resource competition) relative to other mammalian herbivores49.

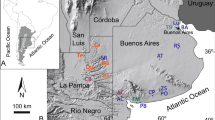

These results, providing the first direct evidence of omnivory in an ancient sloth species, demands reevaluation of the entire ecological structure of mammalian communities in Cenozoic South America, as sloths represented a major component of these ecosystems across the past 34 million years. For instance, in the well-studied Pleistocene Lujanian fauna in Argentina, xenarthrans would have represented almost half of the mammalian herbivore guild, with sloths alone representing almost 20%53. Furthermore, as large herbivores greatly impact the vegetation structure, soil moisture, and the carbon cycle of an ecosystem54, removal of some fossil ground sloth taxa from the continental herbivore guild would change previous estimations of the net primary production required to sustain a given number of megaherbivores, as well as the type of vegetation dominating the biome floor (e.g., grass-dominated versus moss/shrub-dominated55). This would be the case in particular if, in addition to Mylodon, other fossil sloth species also had more versatile feeding behaviors than traditionally thought and would help explain the perplexing and long-assumed paucity of mammalian secondary consumers during the Cenozoic in South America.

Materials and methods

We analyzed hair samples of 15 mammal species: two fossil sloths, five modern xenarthran species under controlled feeding conditions (i.e., zoo specimens, Table 1), and eight wild omnivore species (Table 2, Dataset SI). Diet samples for the zoo specimens also were analyzed directly (Table S3). All amino acid compound specific (AACSIA) data for other mammals available in the literature (45 taxa) were also included, among these: 14 terrestrial primary consumers, 16 terrestrial secondary consumers, and 15 marine consumers. Statistical tests were two-tailed, and analyses were conducted with both parametric (two-sample t-test, ANOVA) and nonparametric (Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis) tests for significance. Groups do not have equal variances (Levene’s test p = 0.005), likely because the omnivore and marine consumers categories both include a broad range of diets (see main text), but differences between groups also were significant under an unequal variance t-test (Welch t test, Table S4).

Sampling and analyses

All samples were analyzed for bulk and amino acid compound specific (AACSIA) δ15N at the Department of Earth Sciences, University of Hawaii at Manoa. To evaluate the temporal homogeneity (or heterogeneity) of the isotopic signal recorded in the modern sloth with a monospecific diet (i.e., Bradypus) and in the fossil species (Mylodon and Nothrotheriops) with unknown diets, hair strands for these three species were sectioned in 0.5 or 1 cm and analyzed for bulk δ15N prior to AACSIA (Fig. 2, Table S7). If significant differences were found among the bulk δ15N of the different hair sections, these were analyzed separately for AACSIA δ15N; otherwise, sections were homogenized. For the fossil samples, hair strands of one individual per species were sectioned in 1 cm increments and analyzed for δ15N and molar C:N ratio (Fig. S1, Table S7). For all the zoo species (except Cyclopes), the proximal 1 cm (expected to more closely record the diets sampled than distal sections, as this represents the most recently formed part of the hair) were homogenized and analyzed for δ15N (bulk and for AACSIA). For Cyclopes, possessing very thin and short hair, entire hair strands were homogenized for both bulk and AACSIA δ15N. Dietary items for the species with mixed diets were isolated and analyzed for bulk δ15N. Mixed diets were homogenized in the proportion of each individual dietary item given to the individual animals at the zoo and then analyzed for δ15N AACSIA. Variability of the isotopic values for the two modern sloths’ diets in the zoo was accounted for by analyzing samples on a weekly, monthly, and yearly basis (Tables S8–S10).

Bulk δ15N values of hair keratin and C:N ratios for the fossil species

The δ15N value of the proximal first centimeter was higher than the remaining length of the hair for both species, so this first centimeter was conservatively excluded for AACSIA (Fig. S1, Table S7). Significant differences (p-value < 0.01) were found between Mylodon darwinii’s hair segments 3–4 plus 7–10 (mean = 2‰ ± 0.1), and segments 2 plus 5–6 (mean = 3.5‰ ± 0.6). Therefore, we homogenized segments 3–4 plus 7–10, and 2 plus 5–6, and analyzed those for AACSIA δ15N (Fig. S1). In contrast, after excluding the first centimeter (δ15N = 17.5‰), the δ15N values of the remaining hair segments of Nothrotheriops are extremely consistent and do not differ significantly from each other (mean = 16‰ ± 0.1, Fig. 2).

Nitrogen isotope analyses of amino acids

Amino acids were chemically isolated and purified from sample material prior to derivatization and esterification in preparation for GC-IRMS analysis, as described in56. Samples were then analyzed using a Thermo Scientific Delta V Plus mass spectrometer interfaced with a Thermo Finnigan Trace GC gas chromatograph via a Thermo Finnigan GC-C III. Amino acids measured using this technique include alanine (Ala), glycine (Gly), isoleucine (Iso), leucine (Leu), lysine (Lys), methionine (Met), phenylalanine (Phe), proline (Pro), serine (Ser), threonine (Thr), tyrosine (Tyr), and valine (Val). Additionally, the terminal amide groups in glutamine (Gln) and aspartamine (Asn) are cleaved during the chemical isolation of amino acids, the result being the conversion of these amino acids to glutamic acid (Glu) and aspartic acid (Asp), respectively. Thus, we measured the isotope values of combined Glu + Gln (termed Glx) and Asn + Asp (termed Asx). Internal reference compounds, L-2-Aminoadipic acid (AAA) and L-(+)-Norleucine (Nor) of known nitrogen isotopic composition, were co-injected with samples and used to determine accuracy and precision. Between triplicate runs of each sample, a suite of these 14 amino acids of known isotopic composition were analyzed; AAA and Nor were also co-injected with these amino acids. For isotopic correction of unknown amino acids, a linear correction is derived from the amino acid suites run immediately before and after the triplicate sample analysis and applied to measured isotope ratios. All amino acids were analyzed in triplicate and isotopic values are reported in δ-notation relative to atmospheric N2.

Ethics

The protocols used to collect hair samples from museum/zoo specimens conform to the legal requirements and institutional guidelines of the Peruvian and US Governments (permit # 003150-SERFOR, PE1620, PE1621, USFWS NY2039715). All applicable international, national, and/or institutional sampling methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. When appropriate, this research adheres to the ARRIVE guidelines.

References

Voss, R. S. & Emmons, L. H. Mammalian diversity in Neotropical lowland rainforests: A preliminary assessment. Bull. Am. Museum Nat. Hist. 230, 1–115 (1996).

Barnosky, A. D. et al. Variable impact of late-Quaternary megafaunal extinction in causing ecological state shifts in North and South America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 856–861 (2016).

Croft, D. A., Engelman, R. K., Dolgushina, T. & Wesley, G. Diversity and disparity of sparassodonts (Metatheria) reveal non-analogue nature of ancient South American mammalian carnivore guilds. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20172012 (2018).

Fariña, R. A. Trophic relationships among Lujanian mammals. Evol. Theory 11, 125–134 (1996).

Fariña, R. A. & Blanco, R. E. Megatherium the Stabber. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 263, 1725–1729 (2006).

Tejada-Lara, J. V. et al. Body mass predicts isotope enrichment in herbivorous mammals. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285, 20181020 (2018).

de Muizon, C. & McDonald, H. G. An aquatic sloth from the Pliocene of Peru. Nature 375, 224–227 (1995).

Croft, D. A. The middle Miocene (Laventan) Quebrada Honda Fauna, southern Bolivia and a description of its notoungulates. Palaeontology 50, 277–303 (2007).

Boecklen, W. J., Yarnes, C. T., Cook, B. A. & James, A. C. On the use of stable isotopes in trophic ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 42, 411–440 (2011).

Lee-Thorp, J. J., Sealy, J. J. C. & van der Merwe, N. J. N. Stable carbon isotope ratio differences between bone collagen and bone apatite, and their relationship to diet. J. Archaeol. Sci. 32, 1459–1470 (1989).

Clementz, M. T., Fox-Dobbs, K., Wheatley, P. V., Koch, P. L. & Doak, D. F. Revisiting old bones: Coupled carbon isotope analysis of bioapatite and collagen as an ecological and palaeoecological tool. Geol. J. 44, 605–620 (2009).

Tejada, J. V. et al. Comparative isotope ecology of western Amazonian rainforest mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007440117 (2020).

Robinson, D. δ15N as an integrator of the nitrogen cycle. Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 153–162 (2001).

McMahon, K. W. & McCarthy, M. D. Embracing variability in amino acid δ15N fractionation: Mechanisms, implications, and applications for trophic ecology. Ecosphere 7, 1–26 (2016).

McClelland, J. W. & Montoya, J. P. Trophic relationships and the nitrogen isotopic composition of amino acids in plankton. Ecology 83, 2173–2180 (2002).

Chikaraishi, Y., Ogawa, N. O., Doi, H. & Ohkouchi, N. 15N/14N ratios of amino acids as a tool for studying terrestrial food webs: A case study of terrestrial insects (bees, wasps, and hornets ). Ecol. Res. 26, 835–844 (2011).

Popp, B. N. et al. Insight into the trophic ecology of yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, from compound- specific nitrogen isotope analysis of proteinaceous amino acids. In Stable Isotopes as Indicators of Ecological Change (eds Dawson, T. E. & Siegwolf, R. T. W.) 173–190 (Elsevier Inc., 2007).

Naito, Y. I., Honch, N. V., Chikaraishi, Y., Ohkouchi, N. & Yoneda, M. Quantitative evaluation of marine protein contribution in ancient diets based on nitrogen isotope ratios of individual amino acids in bone collagen: An investigation at the Kitakogane Jomon Site. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 143, 31–40 (2010).

O’Connell, T. C. ‘Trophic’ and ‘source’ amino acids in trophic estimation: A likely metabolic explanation. Oecologia 184, 317–326 (2017).

Chikaraishi, Y., Ogawa, N. O. & Ohkouchi, N. Further evaluation of the trophic level estimation based on nitrogen isotopic composition of amino acids. In Earth, Life, and Isotopes (eds Ohkouchi, N. et al.) 37–51 (Kyoto Universy Press, 2010).

Steffan, S. A. et al. Trophic hierarchies illuminated via amino acid isotopic analysis. PLoS ONE 8, 1–10 (2013).

Chikaraishi, Y., Kashiyama, Y., Ogawa, N. O., Kitazato, H. & Ohkouchi, N. Metabolic control of nitrogen isotope composition of amino acids in macroalgae and gastropods: Implications for aquatic food web studies. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 342, 85–90 (2007).

Naito, Y. I. et al. Ecological niche of Neanderthals from Spy Cave revealed by nitrogen isotopes of individual amino acids in collagen. J. Hum. Evol. 93, 82–90 (2016).

Nielsen, J. M., Popp, B. N. & Winder, M. Meta-analysis of amino acid stable nitrogen isotope ratios for estimating trophic position in marine organisms. Oecologia https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-015-3305-7 (2015).

Décima, M., Landry, M. R. & Popp, B. N. Environmental perturbation effects on baseline δ15N values and zooplankton trophic flexibility in the southern California current ecosystem. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 624–634 (2013).

Jarman, C. L. et al. Diet of the prehistoric population of Rapa Nui (Easter Island, Chile) shows environmental adaptation and resilience. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23273 (2017).

Kendall, I. P. et al. Compound-specific δ15N values express differences in amino acid metabolism in plants of varying lignin content. Phytochemistry 161, 130–138 (2019).

Ramirez, M. D., Besser, A. C., Newsome, S. D. & McMahon, K. W. Meta-analysis of primary producer amino acid δ15N values and their influence on trophic position estimation. Methods Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13678 (2021).

Hebert, C. E., Popp, B. N., Fernie, K. J., Rattner, B. A. & Wallsgrove, N. Amino acid specific stable nitrogen isotope values in avian tissues: Insights from captive American kestrels and wild herring gulls. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 12928–12937 (2016).

Chikaraishi, Y. et al. Determination of aquatic food-web structure based on compound-specific nitrogen isotopic composition of amino acids. Limnol. Oceanogr. 7, 740–750 (2009).

Steffan, S. A. et al. Microbes are trophic analogs of animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 15119–15124 (2015).

Kendall, I. P., Lee, M. R. F. & Evershed, R. P. The effect of trophic level on individual amino acid δ15N values in a terrestrial ruminant food web. Sci. Technol. Archaeol. Res. 3, 135–145 (2017).

Matthews, C. J. D., Ruiz-Cooley, R. I., Pomerleau, C. & Ferguson, S. H. Amino acid δ15N underestimation of cetacean trophic positions highlights limited understanding of isotopic fractionation in higher marine consumers. Ecol. Evol. 10, 3450–3462 (2020).

Styring, A. K., Sealy, J. C. & Evershed, R. P. Resolving the bulk δ15N values of ancient human and animal bone collagen via compound-specific nitrogen isotope analysis of constituent amino acids. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 241–251 (2010).

Lorrain, A. et al. Nitrogen and carbon isotope values of individual amino acids: A tool to study foraging ecology of penguins in the Southern Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 391, 293–306 (2009).

Lorrain, A. et al. Nitrogen isotopic baselines and implications for estimating foraging habitat and trophic position of yellowfin tuna in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Deep. Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 113, 188–198 (2015).

Hartman, G. Are elevated δ15N values in herbivores in hot and arid environments caused by diet or animal physiology?. Funct. Ecol. 25, 122–131 (2011).

Hartman, G. & Danin, A. Isotopic values of plants in relation to water availability in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Oecologia 162, 837–852 (2010).

Hansen, R. M. Shasta ground sloth food habits, Rampart Cave, Arizona. Paleobiology 4, 302–319 (1978).

McDonald, H. G. & Morgan, G. S. Ground Sloths of New Mexico. Foss. Rec. 3 New. Mex. Museum Nat. Hist. Sci. Bull. 53, 652–663 (2011).

Poinar, H. N. Molecular coproscopy: Dung and diet of the extinct ground sloth Nothrotheriops shastensis. Science 281, 402–406 (1998).

Clack, A. A., MacPhee, R. D. E. & Poinar, H. N. Mylodon darwinii DNA sequences from ancient fecal hair shafts. Ann. Anat. 194, 26–30 (2012).

Höss, M., Dilling, A., Currant, A. & Pääbo, S. Molecular phylogeny of the extinct ground sloth Mylodon darwinii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 181–185 (1996).

Moore, D. M. Post-glacial vegetation in the South Patagonian territory of the giant ground sloth, Mylodon. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 77, 177–202 (1978).

Bargo, M. S., Toledo, N. & Vizcaino, S. F. Muzzle of South American Pleistocene ground sloths (Xenarthra, Tardigrada). J. Morphol. 267, 248–263 (2006).

Rasmussen, M. et al. Response to comment by Goldberg et al. on ‘DNA from Pre-Clovis human coprolites in Oregon, North America’. Science 325, 148 (2009).

Janis, C. M. Correlations between craniodental anatomy and feeding in ungulates: Reciprocal illumination between living and fossil taxa. In Functional Morphology in Vertebrate Paleontology (ed. Thomason, J.) 76–98 (Cambridge U Press, 1995).

Clauss, M., Nunn, C., Fritz, J. & Hummel, J. Evidence for a tradeoff between retention time and chewing efficiency in large mammalian herbivores. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 154, 376–382 (2009).

Vizcaino, S. F., Bargo, M. S. & Cassini, G. H. Dental occlusal surface area in relation to body mass, food habits and other biologic features in fossil xenarthrans. Ameghiniana 43, 11–26 (2006).

McNab, B. K. Energetics, population biology, and distribution of xenarthrans, living and extinct. In The Ecology of Arboreal Folivores 219–232 (Smithsonian Press, 1985).

Davis, L. B. & Birkbak, R. C. On the transfer of energy in layers of fur. Biophys. J. 14, 249–268 (1974).

Clauss, M. et al. The maximum attainable body size of herbivorous mammals: Morphophysiological constraints on foregut, and adaptations of hindgut fermenters. Oecologia 136, 14–27 (2003).

Fariña, R. A., Czerwonogora, A. & Di Giacomo, M. Splendid oddness: Revisiting the curious trophic relationships of South American Pleistocene mammals and their abundance. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 86, 311–331 (2014).

Zhu, D. et al. The large mean body size of mammalian herbivores explains the productivity paradox during the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 640–649 (2018).

Zimov, S. A., Zimov, N. S., Tikhonov, A. N. & Chapin, I. S. Mammoth steppe: A high-productivity phenomenon. Quat. Sci. Rev. 57, 26–45 (2012).

Hannides, C. C. S., Popp, B. N., Landry, M. R. & Graham, B. S. Quantification of zooplankton trophic position in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre using stable nitrogen isotopes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 50–61 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Enrique Cabrejo and all the Huachipa Zoo staff for help during sample collection, C. Mehling, A. Gishlick, and N. Duncan at the American Museum of Natural History, and J. Reichelderfer for support during research in residence in Hawaii. We thank the handling editor, Przemyslaw Gorzelak, and two anonymous reviewers. This is the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology contribution number 11392.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.V.T. and B.N.P. designed research and interpreted data. J.V.T., B.N.P., and N.W. conducted analyses. R.M., T.C., L.B. and C.C. provided samples and/or data. J.V.T., J.J.F., and B.N.P. provided financial support. J.V.T., B.N.P., J.J.F., R.M., and T.O.C. discussed the results. J.V.T. wrote the paper with contributions from co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tejada, J.V., Flynn, J.J., MacPhee, R. et al. Isotope data from amino acids indicate Darwin’s ground sloth was not an herbivore. Sci Rep 11, 18944 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97996-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97996-9

This article is cited by

-

Xenarthrans of the collection of Santiago Roth from the Pampean Region of Argentina (Pleistocene), in Zurich, Switzerland

Swiss Journal of Palaeontology (2023)

-

Description of a fetal skeleton of the extinct sloth Nothrotherium maquinense (Xenarthra, Folivora): Ontogenetic and palaeoecological interpretations

Journal of Mammalian Evolution (2023)

-

Occurrence of the ground sloth Nothrotheriops (Xenarthra, Folivora) in the Late Pleistocene of Uruguay: new information on its dietary and habitat preferences based on stable isotope analysis

Journal of Mammalian Evolution (2023)

-

Spinal fracture reveals an accident episode in Eremotherium laurillardi shedding light on the formation of a fossil assemblage

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.