Medics tend to a patient at the Life Care Center of Kirkland, a long-term care facility linked to several of Washington state’s confirmed coronavirus cases.Credit: David Ryder/Reuters

Seattle, Washington

Rohit Shankar left the virology laboratory at 2 a.m. on Wednesday, and was back at the lab bench by 7 a.m. the same day. “It’s okay,” he says, “I had a doughnut and a coffee.”

Shankar, a medical scientist, and his colleagues at the University of Washington in Seattle are poised to exponentially drive up the number of confirmed cases of the coronavirus disease COVID-19 around the city, in western Washington state. That’s because this week, they began analysing a mountain of nose and throat swabs collected from hospitals in the region. Already, the researchers are seeing clear signs that the virus has infected vastly more people than have been formally detected.

Scientists fear coronavirus spread in countries least able to contain it

Washington state has become the United States’ ground zero for COVID-19, which has now spread to more than 90 countries worldwide in what seems to be a new and dangerous phase of the outbreak. Washington has declared a state emergency, and ten people there have died from the disease. But the number of confirmed cases in Washington — 70 — is still an underestimate resulting from a lack of testing, researchers agree. A genomic analysis posted online on 29 February suggested that hundreds of people in western Washington might already be infected. Academic scientists have mostly been prevented from measuring the extent of the US outbreak because of federal rules restricting the number of labs qualified to run diagnostic tests. But that is changing now, and helps account for why the state's caseload jumped from 10 to 70 this week.

Dozens of virologists and genomicists have now kicked into high gear in Seattle, dropping or adapting projects to devote resources to the outbreak. Researchers are working around the clock to find out how many people have the disease in the area. Others are analysing genomes to reveal how the virus is transmitted or developing new therapies. The scientists are racing to help Washington avoid the fate of Hubei province in China, where more than 2,900 people have died of COVID-19 so far. The coronavirus emerged in the province’s city Wuhan in December, and the initial response from officials was slow.

“We are past the point of containment,” says Helen Chu, an infectious-disease specialist at the University of Washington School of Medicine (UW Medicine) in Seattle. “So now we need to keep the people who are vulnerable from getting sick.”

Helen Chu, an infectious-disease specialist at the University of Washington School of Medicine, is working on several coronavirus research projects.Credit: Julie Nimmergut

Working in shifts

“I remembered to eat around 10 p.m. last night,” says Keith Jerome, director of the clinical virology department at UW Medicine, nodding to an empty pizza box on a conference-room table. In January, his group quickly adapted a PCR test described by the World Health Organization that identifies snippets of the virus’s genome sequence.

But when COVID-19 reached the United States, his team couldn’t check the accuracy of its test — done by analysing samples from people known to have the disease — because of US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations intended to ensure that tests are accurate before clinics rely on them. But researchers became impatient with the pace of the processes as the outbreak hit home. On 29 February, the FDA announced that it would allow certain academic labs to test people for the disease — opening Jerome’s lab to a flood of samples.

Calling all coronavirus researchers: keep sharing, stay open

The lab is now helping hospitals and the state to clinically diagnose cases of COVID-19. Jerome estimates that with its high-throughput molecular-biology equipment, the group can currently screen around 1,000 samples per day — roughly 5 times as many as the state department of health’s lab. “That’s why it’s such a problem to not have labs like this involved in the early days of an outbreak,” Jerome says. Now that they’re rolling, the researchers have plans to bulk up their capacity to 4,000 samples daily. Jerome says they’re quadrupling their equipment with university funds, asking other labs in the city to lend them PCR machines, and adding more researchers to their ranks. “We’re making plans for different shifts around the clock so that we don’t burn people out,” he says.

Because the test is still new, the lab sends positive samples to the state lab for official confirmation. Then the state alerts the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which is responsible for official US case counts.

Undetected spread

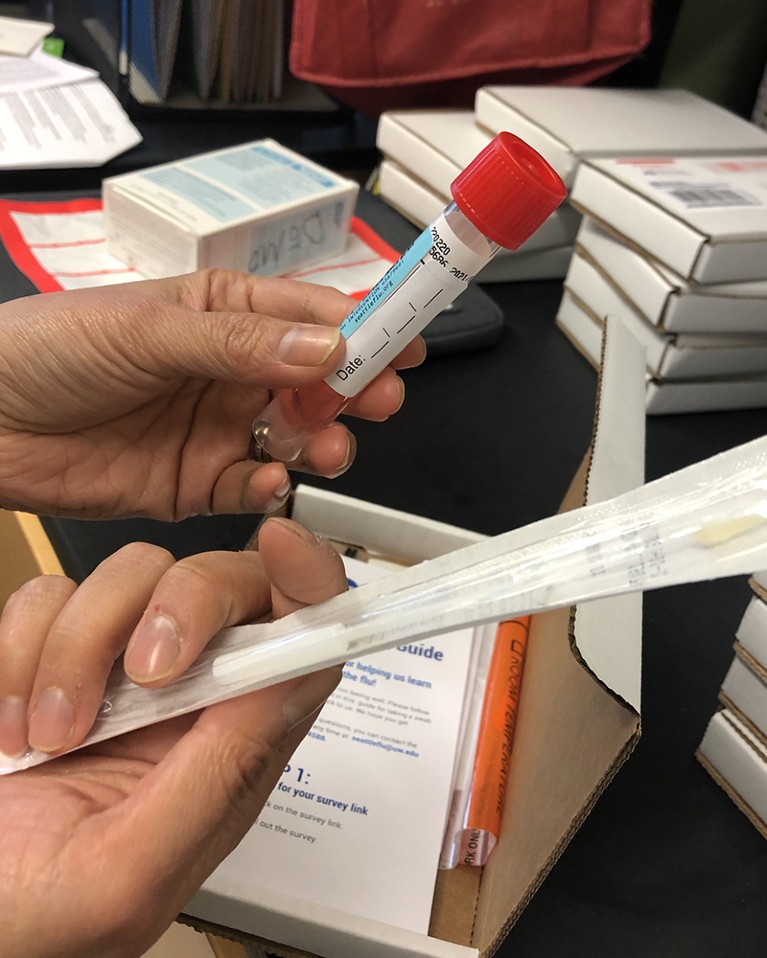

Meanwhile, in Chu’s lab, boxes containing swab kits balance precariously on lab benches and carts. Late last week, her group received the green light from the FDA and the CDC to analyse nose swabs for the novel coronavirus. It’s for a scientific study, rather than as part of the state’s public-health response. Still, the researchers act on the results in real time. If samples test positive, they notify the health department.

Their project stems from the multi-institution Seattle Flu Study, which Chu has co-led since 2018. In that study, participants who feel as if they have a cold or the flu swab their nose and send the sample to the lab, where researchers sequence any influenza-virus genomes they contain. Analyses of these genomes reveal the trail that the flu takes as it passes around households, homeless shelters, office parks and communities in the city.

Medical scientist Rohit Shankar is working overtime to screen people for COVID-19.Credit: Keith Jerome/UW/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center

As COVID-19 overwhelmed China in January, the Seattle Flu Study researchers felt sure that the epidemic would soon spread to the United States — and that they should track that, too. So they customized a genetic test, similar in design to what they'd used for influenza viruses, so that it could identify genetic sequences of the new coronavirus. On 27 February, soon after they they had received clearance to use it, their ‘COVID panel’ detected the virus in a swab from a teenager north of Seattle. His case would prove pivotal because he hadn’t travelled internationally. The team alerted the county health department, and set about sequencing the whole genome of the virus.

After barely 24 hours, the researchers had sequenced the genome. They posted the sequence to an online platform called GISAID. Then a collaborator at Nextstrain, an online project that visualizes the spread of viruses through genomic analyses, compared the genome with dozens of others that had been sequenced around the world. In a series of tweets on 29 February, Nextstrain’s co-founder, computational biologist Trevor Bedford, explained his finding. The sequence contained an unusual genetic variation that matched that of the virus from the first person reported with COVID-19 in the United States, on 20 January — a man treated at a hospital north of Seattle. This meant that the virus had probably been circulating around western Washington for six weeks. Bedford calculated that in that time frame, up to 1,500 people could have been infected.

Time to use the p-word? Coronavirus enters dangerous new phase

In the days that followed, health officials in Seattle reported a rising number of deaths from COVID-19 among older people who hadn’t travelled — and who therefore had caught the disease at home. Washington is now preparing for a deluge of cases. Seattle’s county has even bought a motel in which to isolate people with coronavirus who no longer need hospital support but are still recovering. Yet what is still lacking, says Cassie Sauer, chief executive of Washington State Hospital Association, are diagnostic tests. “Our emergency rooms are being flooded today by people saying they want a test,” she says. Even with the added power at the University of Washington, supplies are limited.

Kits for the Seattle Flu Study include a nose swab, which researchers can now test for the new coronavirus.Credit: Amy Maxmen/Nature

‘Spending money like it’s nothing’

Some of this burden could soon be relieved as the Seattle Flu Study changes course. This week, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in Seattle said that it will furnish the study with another US$5 million. People who feel ill but aren’t in dire need of hospital care can now order the swab kit from the study website. “We’re ramping up to screening 570 tests a day, and hope to do 1,000 per day in a few weeks,” says Lea Starita, a genomicist on the project at UW Medicine. She’s scrambling to find researchers to join the lab and is purchasing new tools. “I’ve been spending money this week like it’s nothing,” she says, listing $390,000 in equipment and reagents off the top of her head.

Dan Wattendorf, who directs efforts to create biotechnology solutions at the Gates Foundation, hopes that people with bearable illnesses will stay at home and order the kit, instead of going to hospitals where they could transmit the virus — or catch it. And if people test positive but aren’t feeling terrible, says Wattendorf, they can isolate themselves. That could prevent an outbreak from growing. “I don’t think we will shut down cities like they did in Wuhan,” Wattendorf says. “But can we have a precision quarantine to keep people from transmitting the disease?”

As the swab kits pile up in Chu’s lab, she mentions more than 2,500 samples collected this year for the flu study. Some might contain the new coronavirus and genomic analyses of those viruses could reveal how they circulated undetected around Seattle. But with the ever-mounting workload, there’s no time to analyse them now. Chu is also involved in a new effort to isolate antibody proteins from people with COVID-19, in the hope that researchers can develop a treatment based on them. And she’s leading a clinical trial at UW Medicine to see whether the experimental antiviral drug remdesivir could treat the disease. “We anticipate that we can start enrolment in a week,” she says.

Chu doesn’t spare a thought for the work she’s put on hold. She’s in triage mode, prioritizing the most urgent questions. “As diagnostic testing ramps up, it will become clear that this is everywhere,” she says. Seattle’s scientists might help Washington to mitigate the outbreak’s harm to lives and the economy, and provide models for other states and countries to follow. Jerome describes how his virology lab has studied dengue fever, malaria and Zika virus — but those outbreaks hit far from Washington . “We’ve sat on the sidelines and helped, but it’s abstract,” he says. “So, work that took us weeks before is now done in hours. Everyone is stepping up.”

Coronavirus latest: global infections pass 90,000

Coronavirus latest: global infections pass 90,000

Time to use the p-word? Coronavirus enters dangerous new phase

Time to use the p-word? Coronavirus enters dangerous new phase

When will the coronavirus outbreak peak?

When will the coronavirus outbreak peak?

As coronavirus spreads, the time to think about the next epidemic is now

As coronavirus spreads, the time to think about the next epidemic is now

More than 80 clinical trials launch to test coronavirus treatments

More than 80 clinical trials launch to test coronavirus treatments

Scientists fear coronavirus spread in countries least able to contain it

Scientists fear coronavirus spread in countries least able to contain it