Abstract

Luminal cytokeratin (CK) expression in breast papillary lesions, and its potential diagnostic utility among other markers in distinguishing between papillomas and papillary carcinomas, has not been previously evaluated. Such expression was determined in 42 papillary lesions (18 papillary carcinomas and 24 papillomas) by immunostaining with a CK5/p63/CK8/18 antibody cocktail. The mean CK8/18 intensity score and percentage of positive cells were significantly higher in papillary carcinomas (227 and 95%, respectively, vs 86 and 42% in papillomas; both P-values <0.0001), whereas the mean CK5 intensity score and percentage of positive cells were significantly lower (7 and 5%, respectively, vs 107 and 58% in papillomas; both P-values <0.0001). Half (9/18) of the papillary carcinomas expressed p63 vs all (24/24) of the papillomas (P=0.0001). P63 expression in papillary carcinoma was always (9/9; 100%) focal/limited in nature (expression in <10% of cells), whereas focal expression was seen in only four (17%) papillomas (P<0.0001). Both differential CK (CK8/18 and CK5) expression and p63 were equally sensitive (100%) for the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma, but differential CK expression was more specific (96 vs 83%), resulting in a greater accuracy. However, the best discriminatory power in the distinction from papilloma was achieved when all three markers were used in combination, resulting in 100% sensitivity and specificity values. It is concluded that breast papillary lesions have differential CK expression profiles that, especially in combination with p63, can be useful for their stratification, potentially also in needle biopsy material, in which more accurate and reproducible characterization is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

By comprising only 1–2% of breast lesions,1 papillary lesions are relatively rare. Despite that, recognizing that a breast lesion is papillary in nature is not particularly difficult for pathologists. On the other hand, distinguishing between various types of papillary lesions can be problematic.2, 3 Such lesions include intraductal papilloma, intraductal papilloma with atypical ductal hyperplasia, intraductal papilloma with ductal carcinoma in-situ, papillary ductal carcinoma in-situ, intracystic (encapsulated3, 4) papillary carcinoma, as well as papillary lesions with unequivocal invasive carcinoma.2

The difficulty in distinguishing between different papillary lesions recapitulates the problem in distinguishing between other intraductal epithelial proliferations that are non-papillary in nature.5, 6, 7 In addition to routine hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections, various immunohistochemical markers have been used to aid in the distinction between such intraductal epithelial proliferations. Of these, high-molecular weight cytokeratins (CKs) traditionally expressed by the basal epithelial/myoepithelial cells of normal breast, including those detected by the 34βE12 antibody (CK1, CK5, CK10 and CK14) and CK6, have been useful in evaluating both non-papillary8, 9, 10, 11 and papillary12, 13, 14, 15 lesions. In general, these studies have found greater expression of high-molecular weight CKs in usual ductal hyperplasia compared with atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in-situ, and in intraductal papillomas compared with papillary carcinomas.

In recent years, it has also been found that in contrast to usual ductal hyperplasia, both atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in-situ preferentially express the low-molecular weight CKs traditionally expressed by luminal epithelial cells of the normal breast, specifically CK8, CK18 and CK19.8, 16, 17 Such expression, combined with decreased/absent high-molecular weight CK expression, has been used to further help distinguish atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in-situ from usual ductal hyperplasia. There are, however, no studies that systematically evaluate the expression of such low-molecular weight CKs in papillary lesions of the breast.

Accordingly, the first goal of this study was to determine the low-molecular weight CK expression profile of intraductal papillary carcinoma of the breast and compare it with that of intraductal papilloma. Our hypothesis was that, similar to non-papillary intraductal proliferations, there would be greater expression in papillary carcinoma. The second goal was to determine the diagnostic utility of differential CK expression in the evaluation of papillary lesions of the breast, especially beyond what a myoepithelial immunostain can provide.

Materials and methods

Case selection and histological review

Consecutive cases of breast papillary lesions were identified via computer search of the database files of the Lauren V Ackerman Laboratory of Surgical Pathology, Washington University Medical Center. One author (OH) reviewed these cases to confirm the diagnosis and select one or more representative paraffin blocks for subsequent immunohistochemical analysis. Given the lack of consensus on the quantitative criteria that distinguish atypical ductal hyperplasia from ductal carcinoma in-situ arising in a papilloma (and accordingly what might constitute an ‘atypical papilloma’)2, 3 only unequivocal cases of intraductal papillomas and intraductal/intracystic/encapsulated papillary carcinomas (hereafter referred to as papillary carcinoma) were further evaluated in this study. Moreover, the study did not include any cases of invasive papillary carcinoma.

Immunohistochemistry

A CK5 (clone XM26)/p63 (clone BC4A4)/ CK8/18 (clone 5D3) prediluted antibody cocktail (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA, USA) was used for the study utilizing an automated immunostainer (Benchmark 720, Ventana Medical Systems, Tuscon, AZ, USA) and manufacturer (Ventana)-provided protocols and reagents as follows: following deparaffinization, heat-induced antigen retrieval and blocking of endogenous peroxidase, sections were incubated for 32 min with the CK5 and p63 antibodies. The secondary biotin-conjugated antibody was then applied for 8 min followed by streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase for 8 min. The reaction was visualized by incubation with diaminobenzidine and hydrogen peroxide for 8 min. Following that, the slides were incubated with the CK8/18 antibody for 32 min. A second biotin-conjugated secondary antibody was then applied for 8 min followed by streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase for 8 min. This reaction was visualized by incubation with fast red for 8 min. Slides were then counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and coverslipped. Normal breast ducts and lobules were used as positive control.

Interpretation of immunohistochemical stains

One author (NNB) interpreted the immunohistochemically stained sections without previous knowledge of the hematoxylin and eosin diagnosis. The expression of both CK8/18 and CK5 were evaluated semiquantitatively utilizing a histological intensity score18 by multiplying the intensity of staining (0, 1, 2 and 3+) by the percentage of cells that stained at each intensity level. These scores were added up to arrive at a final score (ranging from 0 to 300 for each marker). The extent of p63 expression was determined by estimating the proportion of non-peripheral cells that express this marker regardless of intensity. This expression was categorized as negative (no expression), diffuse (homogenous expression in ≥10% of cells), focal (homogenous expression in <10% of cells or heterogeneous expression with at least one discrete focus showing expression in <10% of cells).

Statistical analysis

The expression of CK8/18, CK5 and p63 in papillary carcinoma was compared with that in intraductal papilloma. The Student's t-test was used to compare continuous variables, whereas the χ2-test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables. A P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The utility of the different markers (alone or in combination) in distinguishing between papillary lesions was evaluated by comparing the sensitivity (true positives/true positives + false negatives), specificity (true negatives/true negatives + false positives), positive predictive value (true positives/true positives + false positives), negative predictive value (true negatives/true negatives + false negatives) and accuracy (true positives + true negatives/true positives + false positives + true negatives + false negatives) rates of each marker/combination in correctly classifying the lesions. The 95% confidence intervals for proportions based on a binomial probability distribution were also calculated to assess the accuracy of these estimates in evaluating the papillary lesions. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis, performed using the SPSS for Windows statistical program (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), was also performed to compare the utility of differential CK expression with that of p63 in the evaluation of the papillary lesions.

Regulatory Approval

The study was approved by both the Human Studies Committee at Washington University Medical Center and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board.

Results

Clinical Features and Pathological Diagnosis

In total 38 patients with papillary lesions available for evaluation were identified, including 36 females and 2 males. The age of the patients ranged from 34 to 87 years (mean, 62 years). A total of 42 papillary lesions were retrieved (several patients had more than one lesion), including 26 (63%) from the left breast and 16 (37%) from the right breast. There were 24 (58%) papillomas and 18 (42%) papillary carcinomas.

CK8/18 Expression

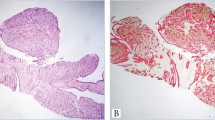

There was greater expression of CK8/18 in papillary carcinomas (Figure 1) compared with papillomas (Figure 2). The mean intensity score in papillary carcinomas (227; range, 115–300) was significantly higher than that in papillomas (86; range, 10–220) (P<0.0001). Additionally, the mean percentage of CK8/18-positive cells in papillary carcinomas (95%; range, 85–100) was significantly higher than that in papillomas (42%; range, 10–85%) (P<0.0001). Moreover, all (100%) papillary carcinomas vs only 3 (13%) papillomas showed CK8/18 expression in ≥80% of lesional cells (P=10−8). In papillomas, the epithelial cells expressing CK8/18 were often intermingled with those expressing CK5, giving a mosaic expression pattern (Figures 2 b and c).

Breast papillary carcinomas immunostained with a CK5/p63/CK8/18 antibody cocktail. The first case (a–c) is characterized by diffuse, strong CK8/18 expression (c) and only focal p63 expression within the papillary cores(c; arrows); more prominent p63 (and CK5) is evident at the periphery (c; asterisk). The second case (d–f) also displays strong, diffuse CK8/18 expression (e, f), as well as rare CK5 positive epithelial cells within the papillary fronds (f; arrows).

Breast papillomas immunostained with a CK5/p63/CK8/18 antibody cocktail. The first case (a–c) has a very prominent mosaic CK8/18/CK5 expression pattern along with diffuse p63 expression (b, c). Although the second case (d–f) also displays diffuse p63 expression, it is characterized by a greater proportion of CK8/18-positive cells (e–f), albeit of weaker intensity than the other case.

CK5 Expression

Papillary carcinomas were completely negative for CK5 in 5 (28%) cases, whereas the remaining carcinomas showed only rare or focal CK5 expression, as exemplified in Figure 1. On the other hand, papillomas always expressed this marker (P=0.013) (Figure 2). The mean intensity score in papillary carcinomas (7; range, 0–20) was significantly lower than that in papillomas (107; range, 20–230) (P<0.0001). The mean percentage of CK5-positive cells in papillary carcinomas (5%; range, 0–15) was also significantly lower than that in papillomas (58%; range, 15–90%) (P<0.0001); only 4 (22%) cases of papillary carcinoma had CK5 expression in greater than 5% of lesional cells.

P63 Expression

Half (9/18) of the papillary carcinomas expressed p63 vs all (24/24) of the papillomas (P=0.0001). P63 expression in papillary carcinoma was always (9/9; 100%) focal in nature, whereas focal expression was limited to 4 (17%) papillomas (P<0.0001), the remainder showing diffuse expression (Figure 2).

Marker Expression in Needle Biopsy and Corresponding Excisional Material

There were two lesions (a papillary carcinoma and a papilloma), in which immunohistochemistry was performed on both needle biopsy and excisional material. On needle biopsy, 100% of the cells in the papillary carcinoma expressed CK8/18 with no CK5 expression, whereas only 20% of cells in the papilloma expressed CK8/18 and 80% expressed CK5. The CK expression profiles in the excisional material were very similar to those seen in needle biopsy material, as 99% of the cells in the corresponding papillary carcinoma expressed CK8/18 with only rare CK5 expression, and 10% of the cells in the corresponding papilloma expressed CK8/18 with 90% expressing CK5. The p63 expression profiles of the papillary carcinoma (negative) and the papilloma (diffuse) were also identical in the needle biopsy and excisional material.

Diagnostic Utility of Differential CK Expression in the Evaluation of Papillary Lesions

On the basis of the different CK8/18 and CK5 expression profiles in papillary lesions of the breast (summarized in Table 1), this differential CK expression appeared to be of potential clinical utility in evaluating such lesions. Accordingly, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy values were determined at different cut-offs (Table 2). This showed that a cut-off of 85/15% for CK8/18 and CK5 expression, respectively, produced the best values with sensitivity, specificity and accuracy rates of 100, 96 and 98%, respectively. These values appeared better than those obtained for p63 (Table 2), a finding that was further confirmed by receiver operating characteristic curve analysis that showed a greater area under the curve for differential CK8/18/CK5 expression (0.998 vs 0.948; Figure 3). However, the best discriminatory power in evaluating the different papillary lesions was obtained when all three markers were used in combination, whereby CK8/18 expression in greater than 80% of cells (with concomitant CK5 expression in <20% of cells) and a negative or only focal p63 expression correctly identified all papillary carcinomas and excluded all papillomas. This resulted in 100% sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value, positive predictive value and accuracy rates (Table 2).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for CK8/18/CK5 and p63 expression in the distinction between papillary carcinoma and papilloma of the breast. This shows that the area under the curve for the cytokeratins (0.998; 95% confidence interval, 0.990–1.005) was greater than that for p63 (0.948; 95% confidence interval, 0.905–1.011) confirming their better discriminatory power.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that the CK8/18 expression profile (as well as that of CK5 and p63) in breast papillary carcinoma is clearly distinct from that in papillomas. We have also demonstrated that differential CK8/18 and CK5 expression has excellent utility (and better than p63) in distinguishing between these two lesions. The best discriminatory power, however, was achieved when CK8/18, CK5 and p63 staining were used together for the distinction. These findings suggest that using these markers in combination can lead to better stratification of papillary lesions of the breast, especially in needle biopsy material, in which more accurate and reproducible distinction is needed. Accordingly, validation of these findings in needle biopsy material is recommended.

Immunohistochemical staining for myoepithelial cells was one of the first adjunctive studies used to attempt to clarify papillary lesions in which a diagnosis cannot easily be made with routine histology.19 Markers that have been used to evaluate for the presence of myoepithelial cells have included smooth muscle actin, p63, P-cadherin and calponin.12, 14, 20, 21, 22 Although most of these (including p6312, 20) have been shown to have good sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma, one has to consider that previous studies have certainly included cases that fit the morphological criteria for papillary carcinoma, but had myoepithelial cells discontinuously present within the lesion,12, 21, 22 including one reporting an under-diagnosis rate of 30% with the use of myoepithelial markers alone for the diagnosis.21 Thus, myoepithelial stains cannot completely solve the diagnostic dilemma that some papillary lesions pose. The findings of our current study are clearly in concert with previous studies, as there was significant overlap in the p63 expression patterns of papillomas and papillary carcinomas. Although diffuse p63 expression was only seen in papillomas and complete lack of expression was limited to papillary carcinomas, half of our papillary carcinoma cases still maintained some level of expression. Accordingly, if only absence of p63 staining was used to classify a lesion as malignant, 50% of papillary carcinomas would be misdiagnosed as benign. On the other hand, if one also included reduced p63 expression (focal; as defined in this study) as a criteria of malignancy, 13% of the papillomas would be misdiagnosed as malignant. Only when CK expression was additionally used for discrimination (see below) were we able to accurately characterize all of the papillary carcinomas, including those with focal p63 expression.

Apart from the issue of myoepithelial cells, the difficulty in distinguishing between different papillary lesions is often secondary to the difficulty of categorizing the nature of the epithelial proliferation within these lesions. Consequently, nonmyoepithelial immunohistochemical stains have recently been used to try to elucidate the character of these proliferations.19, 23, 24 Several studies have utilized high-molecular weight CKs, such as CK5/6 and CK14 and those targeted by the 34βE12 antibody, in the evaluation of papillary lesions with benign papillary lesions consistently showing increased high-molecular weight CK expression when compared with papillary carcinomas.12, 13, 15, 21 Although these studies (as does ours) show that high-molecular weight CK expression is useful in discriminating between different papillary lesions, there is still a certain degree of overlap in the expression patterns in papillomas and papillary carcinoma, which appears to limit their diagnostic utility.

Given that high-molecular weight CK and myoepithelial markers may not completely resolve the differential diagnosis of breast papillary lesions, we wanted to investigate whether luminal/low-molecular weight CK expression might be useful in this regard. Although CK8/18 has been used in combination with CK14 to demonstrate the differential expression in ductal proliferations ranging from florid epithelial hyperplasia to invasive ductal carcinoma,25 to the best of our knowledge its use in papillary lesions has only been reported once before in a single case of solid papillary breast carcinoma,26 in which diffuse strong CK8/18 expression was found.

Accordingly, we first set out to detail the expression patterns of this marker in breast papillomas and papillary carcinomas. Because we wanted to characterize the ‘classic’ expression profile in these cases, we purposefully excluded equivocal cases, including papillomas involved by any degree of atypical ductal hyperplasia/ductal carcinoma in-situ (atypical papillomas). One may certainly question the decision to exclude atypical papillomas,1, 27 a diagnostically challenging category of papillary lesions, from this study. Although the exclusion of this category of papillary lesions resulted in a smaller study population (a potential limitation of our study), it is our strong belief that one should first characterize the expression pattern(s) of any ‘new’ marker (immunohistochemical or otherwise) in well-characterized, non-equivocal cases before evaluating more controversial examples.

We have clearly shown that the CK8/18 expression profile of papillary carcinomas is quite distinct from that of papillomas with significantly higher intensity scores and greater percentage of positive cells. In most cases, CK8/18 expression appeared to be the opposite image of CK5 expression, with only occasional cells showing dual expression (more so in papillomas; Figure 2). Although we tested this in only two cases, we also found that the CK8/18 and CK5 profiles in needle biopsy specimens matched those in the corresponding excisional specimens. From a potential diagnostic standpoint, all papillary carcinomas expressed CK8/18 in 85% or greater of epithelial cells (with concomitant CK5 expression in <15% of cells), whereas only one papilloma had such expression. Using this cut-off, we found that this differential CK expression had a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 96%, a positive predictive value of 95%, a negative predictive value of 100% and an accuracy of 98% for the evaluation of papillary lesions indicating an excellent discriminatory power. Moreover, differential CK expression performed better than p63 (as an individual immunostain) in stratifying these lesions.

As often is the case when different diagnostic tests are used in combination, we found that using CK8/18, CK5 and p63 together (as part of an antibody cocktail) resulted in a greater discriminatory power than when these immunostains were used individually with sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy rates of 100% (Table 2). The inclusion of both CK8/18 and CK5 within the cocktail was very good at highlighting the mosaic appearance of many papillomas (Figure 2) and, when prominent, even negated the need for estimating the percentage of cells positive for each marker. At this point, one should state that it remains to be determined whether the excellent performance of this antibody cocktail holds true with more equivocal cases and in larger series of needle biopsy material. In fact, we are currently in the process of finalizing one such study specifically evaluating needle biopsy material.

Apart from the issue of validation in a separate data set, there are two other questions that need to be addressed regarding the use of these markers in combination for the evaluation of breast papillary lesions. The first is why using both CK8/18 and CK5 is superior to using CK5 alone for the evaluation of papillary lesions; and the second is why evaluating the expression of these markers on a single section is more beneficial than using them individually on different sections. There are several arguments that support the use of these markers together on a single slide: As noted above, using an antibody cocktail on a single section allowed for direct comparison of CK5-positive and CK8/18-positive cells and excellent visualization of mosaic staining when present; additionally, it arguably allows for easier determination of the proportional expression of each CK. Although not specifically addressed in this study, this combination may also be useful to better distinguish between papillomas secondarily involved by usual ductal hyperplasia and those secondarily involved by atypical ductal hyperplasia and/or ductal carcinoma in-situ, in a manner similar to their utility in discriminating between non-papillary intraductal epithelial proliferations.8, 16, 17 Another argument for using CK8/18 in the evaluation of papillary lesions is that its inclusion can provide a ‘positive reaction’ to support a diagnosis of malignancy (papillary carcinoma), instead of just a negative reaction that might be obtained with only CK5 (and/or p63). Of note, this latter rationale has been used to argue (successfully) for using α-methylacyl-CoA racemase in the evaluation of atypical foci in prostate needle biopsy material, a widely accepted practice in contemporary surgical pathology.28 Finally, using these three markers in combination as part of an antibody cocktail could prove to be essential for the evaluation of breast needle biopsy tissue with limited diagnostic material, whereby cutting and immunostaining multiple sections could potentially lead to loss of the diagnostic focus/foci in question. We have undoubtedly encountered this in routine clinical practice and this issue has certainly contributed to the increasing use of other antibody cocktails in the evaluation of limited diagnostic tissue from other organs, again most notably those originating from the prostate gland.

Interestingly, our data illustrating the complementary nature of using more than a single immunohistochemical marker to make a reliable distinction between papilloma and papillary carcinoma is very similar to that in a recent study by Grin et al29 in which they used CK5 and estrogen receptor immunostains on separate slides and obtained a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 100% for the diagnosis of atypical lesions. The single case that was misclassified in their study was an example of high-grade ‘basal-like’ ductal carcinoma in-situ, which was diffusely CK5 positive and lacked estrogen receptor expression. It should be noted that such a case could also be misclassified using a CK5/p63/CK8/18 antibody cocktail; however, as the authors of the aforementioned study point out, the high-grade nature of the lesion would make a benign misdiagnosis extremely unlikely. Because apocrine lesions are almost invariably CK8/18-positive and CK5-negative (unpublished observation), their presence within papillomas could potentially also lead to misclassification as malignant if one were to rely solely on the immunohistochemistry. As is the case in diagnostic surgical pathology in general, these examples highlight the importance of always interpreting results of immunohistochemistry in the context of the appearances on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections and that a diagnosis of benignancy or malignancy should never be based solely on the results of one or more immunostains.

In summary, we have shown that papillary lesions of the breast have differential CK and p63 expression profiles that can clearly be utilized in the distinction between papillomas and papillary carcinomas. The best discriminatory power was achieved when these markers were used in combination, especially as part of an antibody cocktail on a single slide to allow for direct comparison of expression levels. Evaluation of additional cases of breast papillary lesions, including less classic examples and those in needle core biopsy material, is needed to further determine the diagnostic utility of this antibody cocktail.

References

Tavassoli FA . Pathology of the Breast, Second ed McGraw-Hill Professional: New York, NY, 1999.

Mulligan AM, O’Malley FP . Papillary lesions of the breast: a review. Adv Anat Pathol 2007;14:108–119.

Collins LC, Schnitt SJ . Papillary lesions of the breast: selected diagnostic and management issues. Histopathology 2008;52:20–29.

Collins LC, Carlo VP, Hwang H, et al. Intracystic papillary carcinomas of the breast: a reevaluation using a panel of myoepithelial cell markers. Am J Surg Pathol 2006;30:1002–1007.

Jacobs TW, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ . Nonmalignant lesions in breast core needle biopsies: to excise or not to excise? Am J Surg Pathol 2002;26:1095–1110.

Elston CW, Sloane JP, Amendoeira I, et al. Causes of inconsistency in diagnosing and classifying intraductal proliferations of the breast. European Commission Working Group on Breast Screening Pathology. Eur J Cancer 2000;36:1769–1772.

Rosai J . Borderline epithelial lesions of the breast. Am J Surg Pathol 1991;15:209–221.

Boecker W, Moll R, Dervan P, et al. Usual ductal hyperplasia of the breast is a committed stem (progenitor) cell lesion distinct from atypical ductal hyperplasia and ductal carcinoma in situ. J Pathol 2002;198:458–467.

Lacroix-Triki M, Mery E, Voigt JJ, et al. Value of cytokeratin 5/6 immunostaining using D5/16 B4 antibody in the spectrum of proliferative intraepithelial lesions of the breast. A comparative study with 34betaE12 antibody. Virchows Arch 2003;442:548–554.

Moinfar F, Man YG, Lininger RA, et al. Use of keratin 35betaE12 as an adjunct in the diagnosis of mammary intraepithelial neoplasia-ductal type—benign and malignant intraductal proliferations. Am J Surg Pathol 1999;23:1048–1058.

Otterbach F, Bankfalvi A, Bergner S, et al. Cytokeratin 5/6 immunohistochemistry assists the differential diagnosis of atypical proliferations of the breast. Histopathology 2000;37:232–240.

Tse GM, Tan PH, Lui PC, et al. The role of immunohistochemistry for smooth-muscle actin, p63, CD10 and cytokeratin 14 in the differential diagnosis of papillary lesions of the breast. J Clin Pathol 2007;60:315–320.

Tan PH, Aw MY, Yip G, et al. Cytokeratins in papillary lesions of the breast: is there a role in distinguishing intraductal papilloma from papillary ductal carcinoma in situ? Am J Surg Pathol 2005;29:625–632.

Douglas-Jones A, Shah V, Morgan J, et al. Observer variability in the histopathological reporting of core biopsies of papillary breast lesions is reduced by the use of immunohistochemistry for CK5/6, calponin and p63. Histopathology 2005;47:202–208.

Ichihara S, Fujimoto T, Hashimoto K, et al. Double immunostaining with p63 and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins distinguishes borderline papillary lesions of the breast. Pathol Int 2007;57:126–132.

Boecker W . Preneoplasia of the breast : a new conceptual approach to proliferative breast disease. Saunders Elsevier: Munich, 2006.

Abdel-Fatah TM, Powe DG, Hodi Z, et al. Morphologic and molecular evolutionary pathways of low nuclear grade invasive breast cancers and their putative precursor lesions: further evidence to support the concept of low nuclear grade breast neoplasia family. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:513–523.

McCarty Jr KS, Miller LS, Cox EB, et al. Estrogen receptor analyses. Correlation of biochemical and immunohistochemical methods using monoclonal antireceptor antibodies. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1985;109:716–721.

Troxell ML, Masek M, Sibley RK . Immunohistochemical staining of papillary breast lesions. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2007;15:145–153.

de Moraes Schenka NG, Schenka AA, de Souza Queiroz L, et al. Use of p63 and CD10 in the differential diagnosis of papillary neoplasms of the breast. Breast J 2008;14:68–75.

Moritani S, Ichihara S, Kushima R, et al. Myoepithelial cells in solid variant of intraductal papillary carcinoma of the breast: a potential diagnostic pitfall and a proposal of an immunohistochemical panel in the differential diagnosis with intraductal papilloma with usual ductal hyperplasia. Virchows Arch 2007;450:539–547.

Hill CB, Yeh IT . Myoepithelial cell staining patterns of papillary breast lesions: from intraductal papillomas to invasive papillary carcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;123:36–44.

Saddik M, Lai R . CD44s as a surrogate marker for distinguishing intraductal papilloma from papillary carcinoma of the breast. J Clin Pathol 1999;52:862–864.

Tse GM, Tan PH, Ma TK, et al. CD44s is useful in the differentiation of benign and malignant papillary lesions of the breast. J Clin Pathol 2005;58:1185–1188.

Denoux Y, Lebeau CH, Michels JJ, et al. Double immunohistochemical labeling technique applied to different types of cytokeratins in epithelial proliferations of the breast. Biotech Histochem 2003;78:23–26.

Gurbuz Y, Ozkara SK . Clear cell carcinoma of the breast with solid papillary pattern: a case report with immunohistochemical profile. J Clin Pathol 2003;56:552–554.

Page DL, Salhany KE, Jensen RA, et al. Subsequent breast carcinoma risk after biopsy with atypia in a breast papilloma. Cancer 1996;78:258–266.

Hameed O, Humphrey PA . Immunohistochemistry in diagnostic surgical pathology of the prostate. Semin Diagn Pathol 2005;22:88–104.

Grin A, O’Malley FP, Mulligan AM . Cytokeratin 5 and estrogen receptor immunohistochemistry as a useful adjunct in identifying atypical papillary lesions on breast needle core biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1615–1623.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Presented in part at the 97th Annual Meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Denver, CO, March 2008.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reisenbichler, E., Balmer, N., Adams, A. et al. Luminal cytokeratin expression profiles of breast papillomas and papillary carcinomas and the utility of a cytokeratin 5/p63/cytokeratin 8/18 antibody cocktail in their distinction. Mod Pathol 24, 185–193 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.197

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.197

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

CXCL1 Derived from Mammary Fibroblasts Promotes Progression of Mammary Lesions to Invasive Carcinoma through CXCR2 Dependent Mechanisms

Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia (2018)

-

Keratin expression in breast cancers

Virchows Archiv (2012)