Abstract

The production of liquid fuels and fine chemicals often involves multi-step reaction processes with selective hydrogenation as one of the key steps. This step most often depends on high-pressure excess hydrogen gas, fossil resources, and newly prepared metallic catalysts. Here we describe an approach to tune activity and selectivity toward transfer hydrogenation of renewable biomass derivatives over commercially available Pd/C using liquid hydrosilane as hydrogen source. The appropriate control of water-doping content, acid type, reaction temperature, and liquid H− donor dosage permits the selective formation of four different value-added products in high yields (≥90%) from bio-based furfural under mild reaction conditions (15–100 °C). Mechanistic insights into the hydrosilane-mediated cascade reactions of furfural are obtained using isotope labeling. The catalyst is recyclable and can selectively reduce an extensive range of aromatic carbonyl compounds to the corresponding alcohols or hydrocarbons in 83–99% yield, typically at 25–40 °C.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Controllable catalysis is one of the most efficient ways to tune activity and selectivity for competitive and cascade multi-step reactions in a single pot1,2,3,4. This catalytic strategy can not only increase the productivity of existing catalytic processes, but also reduce waste generation. A diversity of functional catalytic materials with unique properties have been developed via complex and renewed synthetic procedures to achieve this goal5,6,7,8,9. Some characteristics such as the valence state of metal species, surface wettability, and nanostructure directly affect the catalytic performance of the solid materials5,6,7,8,9. In addition, electronic effects between solid supports and reduced metal particles or soluble species have recently been shown to be responsible for superior activity10, 11. An additional effect can be attained by deactivation or activation of the metal catalysts with water for both aqueous- and vapor-phase reactions12, 13. From practical and economic points of view, it is desirable to tune the chemoselectivity of commercially available metal catalysts by considering the above issues, as it directly impacts the profitability and convenience in industrial applications.

Selective hydrogenation of aromatic carbonyl compounds with metal catalysts using relatively high-pressure H2 as reductant is an important route to prepare the corresponding alcohols or hydrocarbons14,15,16,17,18. In some cases, H2 at low pressures (as low as 1 bar) can also be used to achieve efficient hydrodeoxgenation, albeit at much higher reaction temperatures (≥300 °C)19, 20. Lignocellulosic biomass composed of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin is the most abundant and oxygen-rich renewable organic carbon source, and due to this it has been extensively explored for the production of biofuels and valuable chemicals21,22,23. In particular, much attention has been paid to the development of efficient methods to deoxygenate bulk biomass derivatives with controllable or desirable selectivity24,25,26,27. For example, bio-based aromatic carbonyl compounds like furfural (FUR) and veratraldehyde can be produced from lignocellulosic biomass28, 29. These compounds can be further selectively transformed into other target products like alcohols and hydrocarbons30,31,32, while the versatility of commercial metal catalysts for tunable hydrogenation of biomass-derived platform molecules, concurrently involving other types of reactions, are much less studied.

Pd/C is a commercial and extensively used catalyst. In the absence of H2, the supported Pd catalyst promotes decarbonylation and decarboxylation of aldehydes and carboxylic acids, as well as related biomass derivatives33,34,35. However, when sole Pd particles are used as catalyst for hydrogenation of FUR in the presence of H2, a wide range of competing reactions, such as unselective hydrogenation of the furan-ring or aldehyde groups and incomplete hydrodeoxygenation, have been reported36,37,38. Introduction of a secondary metal species or acidic sites into the catalyst is frequently adopted as an effective remedial measure to significantly limit side reactions, and to acquire target products in satisfactory yields39,40,41,42,43. It would be economically attractive if simpler approaches could be developed for the modification of Pd species to control reaction selectivity and product distribution44, 45.

In this work, a simple water-doping method in combination with variation of reaction parameters, such as acid type, temperature and H-donor dosage, is used to tune the chemoselectivity and activity of Pd/C in catalytic conversion of FUR to four different valuable products in excellent yields of ≥90%: furfuryl alcohol (FFA), 2-methylfuran (MF), 5-hydroxy-2-pentanone (HPT), and n-butyl levulinate (BL). Instead of H2 gas, the liquid H-donor polymethylhydrosiloxane (PMHS) is employed, which is an inexpensive, non-toxic, and water/air insensitive coproduct of the silicone industry46. Isotope labeling studies are further conducted to substantiate the reaction pathway. Moreover, the recyclability of the catalyst system and the scope of analogous reactions are also examined under benign reaction conditions (25 and 40 °C).

Results

Optimization of reaction parameters

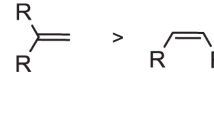

Considering that MF formed in the present catalytic system proved more thermodynamically unfavorable than other value-added products on the basis of density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Fig. 1), emphasis was placed on MF formation. To tune the chemoselectivity in a convenient and economic way, initial studies on catalytic transfer hydrogenation of FUR over commercial and water-doped Pd/C were performed to investigate the product distribution mediated with a slight excess of PMHS (2–4 equiv. H−) under variable reaction conditions, and the results are shown in Table 1. Dry 5 wt% Pd/C at a catalyst dosage of 2 mol% was observed to be highly efficient for hydrogenation of FUR with quantitative conversion at 100 °C after 2 h, giving the dominant product HPT with a very good yield of 81% (Table 1, entry 1).

Schematic illustration of products derived from FUR and aromatic carboxides. Reaction routes to dominant products (red-colored) occur from carbonyl compounds (blue-colored) over Pd/C-wet and PMHS (2.2 or 4.4 equiv. H−) with or without an acidic additive. LA Lewis acid, BA Brønsted acid. Values in parentheses are DFT-computed free energies relative to FUR

Although the used amount of hydride seems insufficient (2.2 equiv. H− relative to FUR by calculation) for the overall catalytic process, extra hydride was possibly provided by smaller fragments of PMHS, or may have derived from minor −[H2SiO]− units present besides a majority of −[H(Me)SiO]− in PMHS, thus contributing to the complete reduction of FUR to HPT.

In contrast, Pd supported on metal oxides (ZrO2 and Al2O3) gave both MF and HPT in almost the same yields (30–40%; Supplementary Table 1), while other metals (Ru/C, Pt/C, Ni/C, and Co/C) were nearly inactive for FUR conversion (1–30%; Supplementary Table 1), only affording low yields of FFA (0–15%) and MF (0–2%). This difference hints at a crucial role of Pd species and their surroundings in reaction control.

Modification of Pd/C with trimethylchlorosilane (TMC) showed a great increase in hydrophobicity, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1. The water contact angle increased from 25° (Pd/C) to 136° (Pd/C-TMC). As a result, the yield of HPT further increased from 81 to 92% (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). This finding indicates that the superior hydrophobicity of Pd/C-TMC is favorable for Pd species being more available to hydrophobic PMHS and chlorobenzene (PhCl), and that the formation of more HPT most likely derives from MF intermediate. It is also worth noting that hydrogen gas may be formed in situ by dehydrogenative condensation of PMHS with n-butanol, which is greatly facilitated by the increased hydrophobicity of Pd/C surface47. This process was estimated to be favorable for hydrogenation of C=C bond in furan-ring via metal hydride route37, thus further promoting the formation of HPT from FUR. On the other hand, Pd/C-dry doped with suitable amounts of water suppressed the transformation of MF into HPT (Supplementary Table 2) and the formation of hydrogen gas, wherein the highest MF yield (90%) and turnover frequency (TOF 22.5 h−1) could be obtained in the presence of 50 wt% water-pretreated Pd/C-dry (Table 1, entry 3). Notably, the increase of doping water content from 10 to 70 wt% did not affect the cascade hydrogenation of FUR to FFA and then to MF (Supplementary Table 2). Thus, the hydrogenation of the furan-ring is effectively restrained when using water-doped Pd/C. This interpretation is consistent with the relatively low, gradually decreasing yields of tetrahydrofurylalcohol (THFA) from 7 to below 1% (Supplementary Table 2), when the water content increased from 10 to 70 wt%. The doping with water has been reported to accelerate the formation of Pd048, and to stabilize the charged species in the reaction system49, which may contribute to the pronounced selectivity. This interpretation is supported by the finding that direct addition of water (50 wt% relative to Pd/C-dry; ca. 1:42 (v/v) relative to n-butanol) into the solvent (n-butanol) did not affect the product distribution under identical reaction conditions, due to lack of dispersed water being rapidly adsorbed onto Pd/C surface. However, the addition of twice the amount of PMHS directly led to the continuous conversion of MF to HPT (88% yield; Table 1, entry 4), wherein tandem partial hydrogenation of the furan-ring to 2,3-dihydro-5-methylfuran (DHMF) and ring-opening reactions might occur. This can be well supported by significantly reduced FUR conversion (as low as 42%) and higher total yields of MF and FFA (up to 92%) under identical reaction conditions when much less PMHS (0.2−0.9 mmol H−) was used (Supplementary Table 3).

Without addition of PhCl into the reaction mixture, a complex product distribution (MF: 11%, FFA: 38%, THFA: 35%, HPT: 3%) was detected over the same catalyst Pd/C-wet (Table 1, entry 5), and approximately 10% DHMF was generated from FUR. This loss in selectivity indicates that the release of protonic acid (HCl) from PhCl50 (consistent with the formation of benzene with GC-MS (Supplementary Fig. 2) and acidic pH value of ~1.8) serves to suppress hydrogenation of the furan ring and to enhance the hydriding capability at the aldehyde group. In the absence of PhCl, however, THFA, HPT, and FFA formed together with MF at variable reaction temperatures of 40–100 °C after 0.5–2 h (Supplementary Table 4). Interestingly, a high FFA yield of 95% and 4% MF byproduct were obtained from FUR in the absence of PhCl at a low temperature of 15 °C after 12 h reaction (Table 1, entry 6). These results illustrate that the control of hydrogenation was influenced by acidic additive and doping water content, as well as PMHS dosage and reaction temperature and time.

Unexpectedly, the addition of hydrochloric acid (HCl) did not give desirable yields of MF (59%) as the use of PhCl (90%; Supplementary Table 5). Instead, more n-butyl levulinate (BL, yield: 32%) was generated using HCl (Supplementary Table 5), which could be derived from alcoholysis of FFA with n-butanol in the presence of water (mainly residing in concentrated HCl)51. This result is in agreement with a previous report43, where medium Brønsted acid promotes the hydrodeoxygenation process catalyzed by a metal (e.g., Pt), while strong acid (e.g., HCl) may result in the condensation reaction. On the other hand, this distinction in product selectivity between two different acid additives (conc. HCl and PhCl) can be partially ascribed to the difficulty in the access of hydrophobic PhCl to wet Pd/C, thus slowing down the in situ release of HCl that facilitates the hydrodeoxygenation of FUR or FFA to yield MF but may cause side reactions if used in a relatively large amount. A series of metal chlorides containing crystal water (NiCl2ˑ6H2O, CrCl3ˑ6H2O, ZrOCl2ˑ8H2O, AlCl3ˑ6H2O, and FeCl3ˑ6H2O) were used instead of PhCl to optimize the selectivity toward BL (Supplementary Table 5). Accordingly, NiCl2ˑ6H2O could promote the synthesis of FFA with a moderate yield of 68% (Supplementary Table 5), while CrCl3ˑ6H2O and ZrOCl2ˑ8H2O (Supplementary Table 5) with relatively higher acidity were favorable for further conversion of FFA (11–22% yield) to difurfuryl ether (DFE, 25–32%). AlCl3ˑ6H2O and FeCl3ˑ6H2O could efficiently catalyze the tandem FUR hydrogenation to FFA and its subsequent alcoholysis, yielding 70–83% BL (Supplementary Table 5). Interestingly, the Pd/C-wet catalyst prepared by doping of Pd/C-dry with D2O resulted in BL with an additional 1 amu (m/z = 173), as illustrated by GC-MS (Supplementary Fig. 3). This showed that proton exchange occurred between D2O and active hydrogen species such as enol intermediates and PMHS, in the reaction processes, which also hints that the doped water affected the stability of the charged species of PMHS (Si+ H−) along with selectivity for cascade reactions. The absence of HPT and quite low MF yield of 12% (Table 1, entry 7) indicate that the Lewis acid was active for etherification and alcoholysis of FFA52, while the succeeding hydrodeoxygenation of FFA to MF was greatly hindered, possibly due to the absence of free protonic acid.

The solvent effect was studied using nonpolar, aprotic polar, and protic solvents. In comparison with aprotic polar (dimethyl formamide (DMF) and THF) and nonpolar (n-hexane and CH2Cl2) solvents, protic solvents (methanol, ethanol, n-butanol, and n-hexanol) were more beneficial for the formation of MF from FUR at 100 °C after 2 h (Supplementary Table 6). Especially, n-butanol with medium polarity proved more favorable for producing MF (up to 90% yield). These results indicated a role of solvent protons taking part in the direct conversion of FUR to MF via FFA. Presumably, as a consequence of the mild reaction conditions, the carbon balance of all the above studied reactions was above 90%. Notably, comparable MF yields of 87 and 85% could be achieved by using a much lower Pd dosage of 0.5 and 1.0 mol% after FUR had reacted in n-butanol at 100 °C for 4 and 3.5 h, respectively (Supplementary Table 7).

Molecular H2 is a frequently used hydrogen source, but requires higher reaction temperature (50–120 °C) and higher excess H2 (0.5−2 MPa) than the PMHS-mediated hydrogenation process (15 °C and 2.2 equiv. H−; Table 1, entry 6) to synthesize FFA in yields of typically lower than 85% from FUR over Pd catalyst39, 53. On the other hand, much higher H2 pressure (e.g., 6 MPa) or higher reaction temperature (e.g., 200 °C) were involved to achieve moderate THFA yields (ca. 80%) catalyzed by single Pd particles37, 38, 40. The activation energy for partial hydrogenation of FUR to FFA under H2 was calculated to be lower than that for decarbonylation of FUR to furan over Pd catalysts, but the latter was favored by thermodynamics54. For the production of MF in the atmosphere of H2, an additional step via either hydrogen-assisted dehydration of FFA or deoxygenation of a methoxy intermediate was needed54, while the co-addition of a modifier (e.g. thiols) or metal (e.g. Ru) was necessary to give moderate yields of MF46, 55. In contrast, the present catalytic system avoids the occurrence of decarbonylation and the C=C bond reduction, selectively producing four specific products: FFA, MF, BL, and HPT (with ≥90% yields) under mild reaction conditions (as low as 15 °C and 2.2 equiv. H−).

Catalyst recyclability

In order to probe the industrial feasibility of this catalytic system, the recyclability of Pd/C-wet in the conversion of FUR to MF was examined under optimal reaction conditions (Fig. 2). Importantly, the results showed that the catalyst could be reused for ten consecutive reaction cycles at near-constant yields (87–95%) and selectivities (90–98%) of MF. It should be noted that the incomplete drying (or washing) of the recycled catalyst may lead to the content of water exceeding 50 wt% in the next run, thus resulting in a slight decrease of activity (e.g. in the eighth cycle of Fig. 2), which is consistent with the results in Supplementary Table 2. After the tenth cycle, ICP analysis of the recovered Pd/C revealed that <0.2 ppm Pd species had leached into the mixture, and the BET surface area was only slightly decreased from 807 to 784 m2/g, as illustrated by N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms (Supplementary Fig. 4). The agglomeration degree of Pd particles on fresh and recycled Pd/C was evaluated by TEM (Supplementary Fig. 5), and the particle size distribution was found to slightly increase from 0.7–2.5 nm (fresh) to 0.8–4.1 nm after ten cycles, which is consistent with XRD patterns (Supplementary Fig. 6) that show similar crystallinity. It is worth noting that the slight increase in XRD intensity of the recycled Pd/C, as compared with the fresh counterpart, implied the formation of more Pd0 species during the reaction. The XPS spectrum of Pd 3d of the catalyst (Supplementary Fig. 7) indicated that a fraction of Pd2+ species in Pd/C was completely reduced to Pd0 after the first cycle of reaction. Hence, considering the increase of MF selectivity after catalyst recycling, it maybe deduced that Pd0 seems to be the active species, while Pd2+ in the fresh Pd/C-wet catalyst prior to recycling may catalyze unselective hydrogenation reactions in the presence of PMHS. Pd0 as the active species is supported by the decrease of MF selectivity (ca. 37%) when using Pd(NO3)2 instead of Pd/C (≥90%) as catalyst under identical reaction conditions. Therefore, we deduce that the robust Pd0 species promotes good activity and recyclability of the Pd/C-wet catalyst.

Proposed reaction pathways

To investigate the possible reaction pathway, the product distribution was examined over Pd/C-wet by directly using FFA, MF, and THFA as substrates (Table 2). After reaction at 100 °C for 2 h, FFA was completely converted (entry 1), predominantly yielding MF (37%) and HPT (54%), with minor amounts of THFA (2%) and BL (5%) formed. This distribution indicates that FFA was a key intermediate in the formation of the other products. Interestingly, an increase in MF yield occurred both when using less Pd (84%, entry 2) or lower PMHS dosage (92%, entry 3). Correspondingly, the yield of HPT was significantly lowered to 9 and 1%, respectively. These results confirm that FFA was easily hydrodeoxygenated to MF, while further transformation into HPT occurred if either Pd or PMHS was present at higher loading.

In the absence of protonic acid, Lewis acidic FeCl3ˑ6H2O was able to exclusively catalyze FFA being converted to BL (95% yield, entry 4), further supporting that the in situ formed HCl favored the hydrodeoxygenation of FFA to MF. In lack of protonic acid, alcoholysis of FFA with n-butanol occurred as the primary reaction route to BL with FeCl3. Moreover, the appearance of DFE (entry 4) derived from etherification of FFA also demonstrated that FeCl3 acted as a Lewis acidic species. In parallel, MF was degraded directly to HPT (90% yield, entry 5) under the same reaction conditions as used for FFA conversion (entry 1). In contrast, THFA, HPT, and BL were more stable in the analogous reaction system, giving only low yields of 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (MTHF, 3%; entry 6), DHMF (2%; entry 7), and γ-valerolactone (GVL, <1%; entry 8), respectively. It is noteworthy that the interconversion between HPT and DHMF may happen by addition and removal of water, thus establishing that in situ generated water in hydrodeoxygenation of FUR or FFA to MF is supportive for the formation of HPT from MF via DHMF.

NMR study of the reactions

Mechanistic studies on the selective conversions of FUR to FFA, MF, HPT and BL over Pd/C were performed in situ and ex situ using high-field NMR spectroscopy. These studies served to (i) identify or verify the structures of reaction intermediates and byproducts, (ii) yield insight into the kinetics of the reaction process and main pathway bottlenecks, and (iii) identify positions that experience deuterium incorporation from the hydrosilane or from labile protons when using D2O to wet the catalyst.

In situ NMR spectra were recorded for the hydrogenation of FUR to FFA with PMHS as the hydrogen donor at 25 °C (Fig. 3). The reduction of FUR to FFA was illustrated to proceed rapidly, and the reaction ran to completion within approximately 30 min at 25 °C (Fig. 3a). Minor byproduct formation was detected in form of slow reduction of the furan-ring or the methylhydroxy group to yield THFA and MF, respectively. When deuterated hydrosilane (Ph2SiD2) was applied instead of PMHS as H-donor (hydride) for the hydrogenation of FUR, the resulting FFA was found to incorporate one deuteron at the methylhydroxy position (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the use of D2O-impregnated catalyst did not result in deuterium incorporation into FFA (Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, reduction of the carbonyl group occurred through hydrosilylation and the hydride predominantly derived from the hydrosilane rather than from the solvent that supplies proton.

13C NMR spectra of FUR/FFA hydrogenation using normal/deuterated hydrosilane and Pd/C. a In situ 13C NMR spectra of hydrogenation of FUR to FFA; Reaction conditions: 0.5 mmol FUR, 1.1 mmol H− of PMHS, 2 mol% Pd, 0.75 mL n-butanol-d9 at 25 °C for up to 80 min (initial dead time 5 min). b 13C NMR spectrum of the FFA primary alcohol region showing single deuterium incorporation in the presence of deuterated hydrosilane (Ph2SiD2). The strong signal at 61.4 ppm derives from the butanol solvent

Ex situ NMR studies (as represented in Fig. 3b) were also used for identifying isotope incorporation in the high-temperature conversions of FUR using the deuterated hydrosilane (Ph2SiD2). As shown in Fig. 4, deuterium incorporation into the intermediate FFA and into the product MF was also detected under high-temperature conditions. In contrast, the use of D2O impregnated catalyst and protonated silane induced no deuterium incorporation into the MF (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results manifest that the hydrosilane was the H-donor (hydride) for the cascade hydrogenation and hydrodeoxygenation of FUR to FFA and to MF.

1H-13C HSQC NMR spectra for intermediate and product formed in FUR conversion to MF. Deuterium incorporation into residual intermediate FA (a) and into the product MF (b) is observed over Pd/C in the presence of deuterated silane. Due to the active coupling to quadrupolar deuterium, single deuterated sites appear as triplets and double deuterated sites as pentets. Reaction conditions: 0.5 mmol FUR, 1.1 mmol D−, 2 mol% Pd, 5 mol% PhCl, 2 h

In the conversion of FUR to BL over Pd/C and AlCl3ˑ6H2O, the use of deuterated hydrosilane (Ph2SiD2) resulted in some deuterium incorporation at the methyl group (Fig. 5). Use of the catalyst impregnated with D2O resulted in deuterium incorporation at the C3 and C5 positions, thus showing that BL formed by an enol route encompassing tautomerization reactions (Supplementary Fig. 8), which is consistent with the result of GC-MS (Supplementary Fig. 3). The synthetic route to BL was further tracked by a time series of 13C NMR spectra in FUR conversion to BL (Supplementary Fig. 9b) to obtain a reliable picture of the reaction progress. FUR substrate was completely converted within 5 min and FFA accumulated as a main intermediate. In the reaction setup, FFA was fully converted after 30 min, leading to BL. Co-product formation including MF and the butyl ether of FFA was detected, presumably due to excess H-donor and lack of water, respectively. Corresponding NMR spectra for time series of FUR conversion to HPT were also recorded (Supplementary Fig. 9c), showing that MF was the main intermediate and that it was fully converted after 30 min, whereas both FUR and FFA were fully converted within 5 min.

In addition, intermediates were discovered and structurally assigned using in situ NMR spectroscopy on the non-purified reaction mixtures for BL and HPT formation. In the selective synthesis of BL, 4,5,5-triethoxypentan-2-one (TEPO) is identified by NMR to be a key intermediate (Supplementary Fig. 10a), possibly formed through nucleophilic addition of n-butanol (three molecules) to 4-oxopent-2-enal derived from FFA in the presence of Lewis acid (e.g., AlCl3 and FeCl3). Subsequently, TEPO may convert to BL via consecutive and rapid reactions like removal of butoxy species to give unstable 5-butoxy-5-hydroxypenten-2-one and keto-enol tautomerism56. In HPT formation, only a trace amount of chlorinated byproduct 5-chloro-2-pentanone (Supplementary Fig. 10b) could be detected. This implied that HPT was formed by a route where a carbocation species, like 4-hydroxy-3-penten-1-ylium, was probably generated which can facilitate the addition of hydroxide or chloride (minor) to the C5 position during the furan-ring opening.

Reaction mechanism

Considering the results above, a concise reaction mechanism can be proposed for the selectively catalyzed conversion of FUR to the four different products FFA, BL, MF, and HPT by Pd/C-wet using PMHS as H-donor. As illustrated in Fig. 6, FUR is selectively hydrogenated to FFA via hydrosilylation in the presence of Pd0 and proton. With the addition of Lewis acidic metal chloride (e.g., AlCl3 and FeCl3), FFA can be further transformed into BL via alcoholysis and keto-enol tautomerism, and the promotional role of acid is also supported by the free energy diagrams of intermediates and products (Supplementary Fig. 11). However, some extra Lewis acid sites partially induce etherification of FFA to form DFE (Fig. 6), and the unselective hydrogenation of furan-ring in FFA and acetyl group of BL may take place over a small part of unreduced Pd2+ in Pd/C to yield byproducts of THFA and GVL, respectively. Notably, those coproducts are relatively stable with lower free energies (Supplementary Fig. 11), indicating the significance of appropriate catalyst design in control of the selectivity towards specific target products. Although Pd/C pre-doped with water may poison the Lewis-acid-like Pd2+ by promoting reduction to Pd0 species48, the side reactions cannot be completely suppressed because of inevitable exposure of the oxidizing species in the catalyst to the substrate and products. When PhCl is used instead of Lewis acidic metal chloride, further hydrodeoxygenation of the furfuryl methylsiloxy ether (identified by GC-MS in Supplementary Fig. 12) occurs to predominantly yield MF when using Pd/C-wet via consecutive hydrosilylation, while the hydrolysis of ether to FFA proceeds reversibly. Likewise, a minor amount of MTHF is produced by unreduced Pd2+ species. As more PMHS is used, selective partial hydrogenation of the furan-ring in MF to DHMF, most likely promoted by molecular hydrogen that is formed in situ, followed by acid-catalyzed hydrolysis to HPT can easily happen (Supplementary Fig. 11). Some extra amount of hydride, possibly derived from −[H2SiO]− units and small fragments of PMHS, facilitates the reaction process. It should be noted that the derivatives of PMHS after reaction can be siloxanes or silanols57, 58.

Proposed reaction mechanism for furfural conversion over Pd/C using PMHS as H−donor. Major products, acids, and PMHS derivatives are labeled in red, pink, and blue, respectively. LA Lewis acid, FFA furfuryl alcohol, OPE 4-oxopent-2-enal, BL n-butyl levulinate, DFE difurfuryl ether, THFA tetrahydrofurylalcohol, TEPO 4,5,5-triethoxypentan-2-one, GVL γ-valerolactone, BHPO 5-butoxy-5-hydroxypenten-2-one, MTHF 2-methyltetrahydrofuran, MF 2-methylfuran, DHMF 2,3-dihydro-5-methylfuran, HPY 4-hydroxy-3-penten-1-ylium, HPT 5-hydroxy-2-pentanone, CPO 5-chloro-2-pentanone

Expansion of the reaction scope

The results above show that the selectivity towards the hydrogenation of carbonyl groups or furan-ring and hydrodeoxygenation is tunable by the reaction parameters. In order to examine how broad the substrate base was for reactions with Pd/C-wet and PMHS as H-donor, different carbonyl compounds 1 were employed as substrates and the results are shown in Fig. 7. At 25 °C, benzaldehyde could be selectively converted to benzyl alcohol 2a (94% yield) and toluene 3a (99% yield) after 10 min and 2 h, respectively. By slightly prolonging the reaction time to 0.5 h, 4-biphenyl carboxaldehyde could hydrogenate to 4-biphenylmethanol 2b with a yield of 92%, and the complete hydrodeoxygenation to 4-phenyltoluene 3b (97% yield) took place in the presence of PhCl at 40 °C after 2 h reaction. For the reduction of substituted benzaldehydes (e.g., anisic aldehyde and veratraldehyde), the corresponding alcohols (2c and 2d) were obtained at 25 °C after 2 h, while benzyl compounds (3c and 3d) could be attained at a relatively high temperature of 40 °C after the same reaction time (2 h) in the presence of PhCl. When heterocyclic aldehydes (e.g., 2-thenaldehyde and 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde) were used as substrates, a relatively high reaction temperature (100 °C) was required to achieve good yields (83−93%) of target products (2e, 2f, and 3e). In contrast, the basic 2-pyridinecarboxaldehyde could not be hydrodeoxygenated to 2-picoline 3f (<1%), but only to 2-(hydroxymethyl)pyridine 3e (up to 93%) after being quenched with NaOH solution, which was possibly due to the consumption of in situ formed HCl. Notably, also a series of ketones (e.g., acetophenone, 4-aminoacetophenone, n-butyrophenone, 2-phenylacetophenone, 2-acetonaphthone) could be either partially (2g−2k) or completely (3g−3k) reduced in high yields (85−99%). More importantly, the aromatic rings in these compounds remained intact using the developed catalytic systems, thus making the proposed reaction widely applicable in the reduction of aldehydes and ketones.

Discussion

A versatile catalyst system with Pd/C and PMHS facilitates selective hydrogenation coupled with cascade reactions for efficient conversion of bio-based FUR to the four value-added products FFA, MF, BL, and HPT in excellent yields ≥90% by simple adjustment of the reaction temperature (15–100 °C), PMHS dosage (2−4 equiv. H−), acid type (Brønsted and Lewis acid) and water-doping content (10–70 wt%). Pd0 was established to be the catalytically active species, and doped water along with PMHS and in situ generated acid was found to promote the reduction of residual Pd2+ that otherwise resulted in side product formation. NMR studies on reaction mixtures and isotope-labeling experiments derive the reaction mechanism for the selective hydrogenation, hydrodeoxygenation, alcoholysis, and hydrolysis, respectively. Importantly, the catalyst system was shown to be reusable in at least ten consecutive reactions without noticeable drop in catalytic activity performance. Moreover, a wide reaction scope was demonstrated for the system with several different aromatic carbonyl compounds resulting in selective production of the corresponding alcohols and hydrocarbons in very high yields of 83–99% under mild reaction conditions. This study presents a convenient way to enable the effective control on the performance of a metal catalyst in the selective reduction and coupled cascade reactions, which shows a great potential for enhanced upgrading of biomass derivatives and related compounds.

Methods

Materials

Pd(NO3)2 (>99.9%), RuCl3 (99%), Ni(NO3)2 (98%), Co(NO3)2 (99%), activated charcoal (>99.9%), zirconium dioxide (ZrO2, >99.99%), aluminum oxide (Al2O3, 99.9%), PMHS (average molecular weight = 1700−3200 g/mol), chlorobenzene (99.5%), AlCl3ˑ6H2O (>99.9%), FeCl3ˑ6H2O (99%), NiCl2ˑ6H2O (99.9%), ZrOCl2ˑ8H2O (99.9%), CrCl3ˑ6H2O (98%), tetrahydrofuran (THF, >99.9%), DMF (99.8%), and 1,1,1,3,5,5,5-heptamethyltrisiloxane (≥98.0%) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Industrial Inc. TMC (>98%) was bought from Acros Organics Inc. (USA). 5 wt% Pd/C (Type 87L, dry) was purchased from Alfa Aesar Inc. n-Butyl levulinate (BL, >98.0%), diphenyl(silane-d2) (97 atom % D), deuterium oxide (D2O, 99.9 atom % D), n-butanol-d9 (98 atom % D), furfural (FUR, 99%), FFA (98%), MF (99%), HPT (95%), DHMF (97%), MTHF (>99.5%), GVL (>98.5%) were bought from Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd. n-Butanol (AR), ethanol (AR), methanol (AR), n-propanol (AR), dichloromethane (AR), and n-hexane (AR) were bought from J&K Scientific Ltd. (Beijing). All other reagents were purchased from Beijing InnoChem Science & Technology Co., Ltd. and used without further treatment and purification.

Water-doped Pd/C

Pd/C-wet catalysts were obtained by direct addition of 10–70 wt% water or deuterium oxide into Pd/C-dry (Alfa Aesar Inc.) prior to the reactions, followed by stirring overnight in a sealed tube at room temperature.

Pd/C-TMC preparation

0.5 g of commercial Pd/C and 15 mL cyclohexane were added to a 50 mL round-bottom flask. Then, 3 mL TMC was dropwise added and the resulting mixture stirred at 60 °C for 12 h. Upon completion, the suspension was filtered, washed three times with n-hexane, and dried at 80 °C under N2 overnight to give Pd/C-TMC.

Preparation of other metal catalysts

5 wt% Pd/S (S = Al2O3, ZrO2), and 5 wt% M/C (M = Pt, Ru, Ni, Co) were prepared by incipient wetness impregnation. In a typical procedure, 5 wt% metal species (relative to solid support, around 30 mg metal salts) was firstly dissolved in water (ca. 1.2 mL). Then, solid support was added and the mixture kept stirring at ambient temperature for 24 h. Upon completion, the obtained suspension was dried at 80 °C overnight, and reduced in hydrogen gas with a flow rate of 20 cm3/min at 400 °C (Pd and Pt) or 600 °C (Ni and Co) (heating ramp: 10 °C/min) for 2 h.

Catalyst characterization

Metal contents in the catalysts were determined by ICP-OES (inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer) on an Optima 5300 DV instrument (PerkinElmer Inc.). BET (Brunauer−Emmett−Teller) surface areas of the porous materials were determined from nitrogen physisorption measurements at liquid nitrogen temperature on a Micromeritics ASAP 2010 instrument (Tristar II 3020). Magnified images were obtained with JEM-1200EX TEM (transmission electron microscopy), and the particle size was estimated from TEM images using Nano Measurer 1.2 software. XRD (X-ray diffraction) patterns were recorded by D/max-TTR III X-ray powder diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation source. XPS (X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy) measurements were recorded using a Physical Electronics Quantum 2000 Scanning ESCA Microprobe (Physical Electronics Inc.) equipped with a monochromatic Al Ka anode. The contact angle of a water droplet was measured using a Sorption Analyzer of MB-300G at 25 °C.

Reaction procedures

The reactions with different carbonyl compounds were carried out in a 15 mL Ace tube. In a typical procedure, 0.5 mmol FUR, 2 mol% metal in the catalyst, 0.1 g PMHS (1.1 mmol H−), and 1.5 mL n-butanol with or without 5 mol% PhCl (2.5 μL) or metal chloride (AlCl3ˑ6H2O, FeCl3ˑ6H2O, NiCl2ˑ6H2O, ZrOCl2ˑ8H2O, CrCl3ˑ6H2O) were added into the tube, which was magnetically stirred at 600 rpm for a specific reaction time. The reaction time zero was defined as the tube was placed into an oil bath preheated to 40–100 °C or into a refrigerator maintained at a temperature of 15 °C. After the reaction, liquid products were quantitatively analyzed by GC/GC-MS.

Sample analysis

Liquid products were quantitatively analyzed by GC-FID (Agilent 7890B, HP-5 column: 30 m × 0.320 mm × 0.25 μm) using naphthalene as internal standard and referring to standard curves made from commercial samples. Liquid products and major byproducts were identified with GC-MS (Agilent 6890N GC/5973 MS), and representative spectra are given in Supplementary Fig. 13.

Catalyst recycling

After each cycle of reactions, the remaining catalyst in the mixture was recovered by centrifugation, and successively washed with ethanol and acetone for three times, dried at 60 °C in N2 for 6 h, and directly used for the next run after mixing with 50 wt% water.

Isotope-labeling experiments

For the isotope-labeling study, 1H and 13C NMR 1D spectra as well as 2D 1H-13C NMR spectra (sampling acquisition times of 140 and 50 ms in the 1H and 13C dimension, respectively) of the reaction mixtures were acquired with diphenyl(silane-d2) or normal PMHS in the n-butanol containing 5% MeOD-d4 as the lock substance or in n-butanol-d9 on a Bruker Avance III 800 MHz spectrometer equipped with a TCI cryoprobe.

Quantum chemical calculations

All geometry optimizations and vibrational zero point corrections were performed at b3lyp/6-311+ +g(d,p) level by using Gaussian 09 package59. The solvent n-butanol was employed using the Polarizable Continuum Model60,61,62. The Gibbs free energies of reactants and products in solvent n-butanol at 1 atm, 298.15 K were compared. Notably, DFT computed free energies (kJ/mol) provided for target products, intermediates and by-products were relative to that of FUR.

Data availability

The data sets supporting the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Marimuthu, A., Zhang, J. & Linic, S. Tuning selectivity in propylene epoxidation by plasmon mediated photo-switching of Cu oxidation state. Science 339, 1590–1593 (2013).

Liu, X., Ye, X., Bureš, F., Liu, H. & Jiang, Z. Controllable chemoselectivity in visible-light photoredox catalysis: four diverse aerobic radical cascade reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 11443–11447 (2015).

Tunuguntla, R. H. et al. Enhanced water permeability and tunable ion selectivity in subnanometer carbon nanotube porins. Science 357, 792–796 (2017).

Houck, H. A., Du Prez, F. E. & Barner-Kowollik, C. Controlling thermal reactivity with different colors of light. Nat. Commun. 8, 1869 (2017).

Ma, L., Falkowski, J. M., Abney, C. & Lin, W. A series of isoreticular chiral metal-organic frameworks as a tunable platform for asymmetric catalysis. Nat. Chem. 2, 838–846 (2010).

Wu, S. et al. Thermosensitive Au-PNIPA yolk-shell nanoparticles with tunable selectivity for catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 2229–2233 (2012).

Li, C. et al. Phase and composition controllable synthesis of cobalt manganese spinel nanoparticles towards efficient oxygen electrocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 6, 7345 (2015).

Mistry, H., Varela, A. S., Kühl, S., Strasser, P. & Cuenya, B. R. Nanostructured electrocatalysts with tunable activity and selectivity. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 16009 (2016).

Dai, L. et al. Ultrastable atomic copper nanosheets for selective electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701069 (2017).

Komanoya, T., Kinemura, T., Kita, Y., Kamata, K. & Hara, M. Electronic effect of ruthenium nanoparticles on efficient reductive amination of carbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11493–11499 (2017).

Tamura, M. et al. Formation of a new, strongly basic nitrogen anion by metal oxide modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11857–11867 (2017).

Ohtsuka, H. & Tabata, T. Effect of water vapor on the deactivation of Pd-zeolite catalysts for selective catalytic reduction of nitrogen monoxide by methane. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 21, 133–139 (1999).

Ma, N., Suematsu, K., Yuasa, M., Kida, T. & Shimanoe, K. Effect of water vapor on Pd-loaded SnO2 nanoparticles gas sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf. 7, 5863–5869 (2015).

Blackmond, D. G., Oukaci, R., Blanc, B. & Gallezot, P. Geometric and electronic effects in the selective hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes over zeolite-supported metals. J. Catal. 131, 401–411 (1991).

Ohkuma, T., Ooka, H., Ikariya, T. & Noyori, R. Preferential hydrogenation of aldehydes and ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 10417–10418 (1995).

Gallezot, Á. & Richard, D. Selective hydrogenation of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. Catal. Rev. 40, 81–126 (1998).

Mäki-Arvela, P., Hájek, J., Salmi, T. & Murzin, D. Y. Chemoselective hydrogenation of carbonyl compounds over heterogeneous catalysts. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 292, 1–49 (2005).

Tang, X. et al. Chemoselective hydrogenation of biomass derived 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to diols: key intermediates for sustainable chemicals, materials and fuels. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 77, 287–296 (2017).

Nolte, M. W., Zhang, J. & Shanks, B. H. Ex situ hydrodeoxygenation in biomass pyrolysis using molybdenum oxide and low pressure hydrogen. Green Chem. 18, 134–138 (2016).

Prasomsri, T., Nimmanwudipong, T. & Román-Leshkov, Y. Effective hydrodeoxygenation of biomass-derived oxygenates into unsaturated hydrocarbons by MoO3 using low H2 pressures. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 1732–1738 (2013).

Holm, M. S., Saravanamurugan, S. & Taarning, E. Conversion of sugars to lactic acid derivatives using heterogeneous zeotype catalysts. Science 328, 602–605 (2010).

Li, H., Fang, Z., Smith, R. L. & Yang, S. Efficient valorization of biomass to biofuels with bifunctional solid catalytic materials. Prog. Energ. Combust. Sci. 55, 98–194 (2016).

Saravanamurugan, S., Paniagua, M., Melero, J. A. & Riisager, A. Efficient isomerization of glucose to fructose over zeolites in consecutive reactions in alcohol and aqueous media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5246–5249 (2013).

Shi, J. Single-atom Co-doped MoS2 monolayers for highly active biomass hydrodeoxygenation. Chem 2, 468–469 (2017).

Ma, B., Cui, H., Wang, D., Wu, P. & Zhao, C. Controllable hydrothermal synthesis of Ni/H-BEA with a hierarchical core-shell structure and highly enhanced biomass hydrodeoxygenation performance. Nanoscale 9, 5986–5995 (2017).

Nolte, M. W. & Shanks, B. H. A perspective on catalytic strategies for deoxygenation in biomass pyrolysis. Energy Technol. 5, 7–18 (2017).

Yung, M. M., Foo, G. S. & Sievers, C. Role of Pt during hydrodeoxygenation of biomass pyrolysis vapors over Pt/HBEA. Catal. Today 302, 151–160 (2018).

Lange, J. P., van der Heide, E., van Buijtenen, J. & Price, R. Furfural—a promising platform for lignocellulosic biofuels. ChemSusChem 5, 150–166 (2012).

Zakzeski, J., Bruijnincx, P. C., Jongerius, A. L. & Weckhuysen, B. M. The catalytic valorization of lignin for the production of renewable chemicals. Chem. Rev. 110, 3552–3599 (2010).

Lei, D. et al. Facet effect of single-crystalline Pd nanocrystals for aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural. ACS Catal. 7, 421–432 (2016).

Zhang, G. S. et al. Towards quantitative and scalable transformation of furfural to cyclopentanone with supported gold catalysts. Green Chem. 18, 2155–2164 (2016).

Mukhopadhyay, S. Kinetics and process parameter studies in catalytic air oxidation of veratraldehyde to veratric acid. Org. Process Res. Dev. 3, 365–369 (1999).

Wang, S., Vorotnikov, V. & Vlachos, D. G. Coverage-induced conformational effects on activity and selectivity: hydrogenation and decarbonylation of furfural on Pd(111). ACS Catal. 5, 104–112 (2015).

Mitra, J., Zhou, X. & Rauchfuss, T. Pd/C-catalyzed reactions of HMF: decarbonylation, hydrogenation, and hydrogenolysis. Green Chem. 17, 307–313 (2015).

Verduyckt, J. et al. PdPb-catalyzed decarboxylation of proline to pyrrolidine: highly selective formation of a bio-based amine in water. ACS Catal. 6, 7303–7310 (2016).

Sitthisa, S. et al. Conversion of furfural and 2-methylpentanal on Pd/SiO2 and Pd-Cu/SiO2 catalysts. J. Catal. 280, 17–27 (2011).

Bhogeswararao, S. & Srinivas, D. Catalytic conversion of furfural to industrial chemicals over supported Pt and Pd catalysts. J. Catal. 327, 65–77 (2015).

Biradar, N. S. et al. Single-pot formation of THFAL via catalytic hydrogenation of FFR over Pd/MFI catalyst. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2, 272–281 (2013).

Fulajtárova, K. et al. Aqueous phase hydrogenation of furfural to furfuryl alcohol over Pd-Cu catalysts. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 502, 78–85 (2015).

Nakagawa, Y., Takada, K., Tamura, M. & Tomishige, K. Total hydrogenation of furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural over supported Pd-Ir alloy catalyst. ACS Catal. 4, 2718–2726 (2014).

Hronec, M. et al. Carbon supported Pd-Cu catalysts for highly selective rearrangement of furfural to cyclopentanone. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 181, 210–219 (2016).

Sitthisa, S. et al. Conversion of furfural and 2-methylpentanal on Pd/SiO2 and Pd-Cu/SiO2 catalysts. J. Catal. 280, 17–27 (2011).

Zhang, J. et al. Control of interfacial acid–metal catalysis with organic monolayers. Nat. Catal. 1, 148–155 (2018).

Pang, S. H., Schoenbaum, C. A., Schwartz, D. K. & Medlin, J. W. Effects of thiol modifiers on the kinetics of furfural hydrogenation over Pd catalysts. ACS Catal. 4, 3123–3131 (2014).

Zhang, W., Zhu, Y., Niu, S. & Li, Y. A study of furfural decarbonylation on K-doped Pd/Al2O3 catalysts. . J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 335, 71–81 (2011).

Senapati, K. K. Polymethylhydrosiloxane (PMHS). Synlett 12, 1960–1961 (2005).

Lin, J. D. et al. Wettability-driven palladium catalysis for enhanced dehydrogenative coupling of organosilanes. ACS Catal. 7, 1720–1727 (2017).

Chai, D. I. & Lautens, M. Tandem Pd-catalyzed double C−C bond formation: effect of water. J. Org. Chem. 74, 3054–3061 (2009).

Desai, S. K., Pallassana, V. & Neurock, M. A periodic density functional theory analysis of the effect of water molecules on deprotonation of acetic acid over Pd (111). J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 9171–9182 (2001).

Li, H., Zhao, W. & Fang, Z. Hydrophobic Pd nanocatalysts for one-pot and high-yield production of liquid furanic biofuels at low temperatures. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 215, 18–27 (2017).

Zhang, Z., Dong, K. & Zhao, Z. K. Efficient conversion of furfuryl alcohol into alkyl levulinates catalyzed by an organic-inorganic hybrid solid acid catalyst. ChemSusChem 4, 112–118 (2011).

Lewis, J. D. et al. A continuous flow strategy for the coupled transfer hydrogenation and etherification of 5-(hydroxymethyl)furfural using Lewis acid zeolites. ChemSusChem 7, 2255–2265 (2014).

Mironenko, R. M. et al. Effect of the nature of carbon support on the formation of active sites in Pd/C and Ru/C catalysts for hydrogenation of furfural. Catal. Today 249, 145–152 (2015).

Vorotnikov, V., Mpourmpakis, G. & Vlachos, D. G. DFT study of furfural conversion to furan, furfuryl alcohol, and 2-methylfuran on Pd(111). ACS Catal. 2, 2496–2504 (2012).

Aldosari, O. F. et al. Pd–Ru/TiO2 catalyst—an active and selective catalyst for furfural hydrogenation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 6, 234–242 (2016).

González Maldonado, G. M., Assary, R. S., Dumesic, J. A. & Curtiss, L. A. Acid-catalyzed conversion of furfuryl alcohol to ethyl levulinate in liquid ethanol. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 8990–8997 (2012).

Rahaim, R. J. Jr. & Maleczka, R. M. Jr. C-O hydrogenolysis catalyzed by Pd-PMHS nanoparticles in the company of chloroarenes. Org. Lett. 13, 584–587 (2011).

Li, H. et al. A Pd-catalyzed in situ domino process for mild and quantitative production of 2,5-dimethylfuran directly from carbohydrates. Green Chem. 19, 2101–2106 (2017).

Frisch, M. J., et al. Gaussian 09, Revision D.01 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2013).

Miertuš, S., Scrocco, E. & Tomasi, J. Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilization of ab initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. Chem. Phys. 55, 117–129 (1981).

Miertuš, S. & Tomasi, J. Approximate evaluations of the electrostatic free energy and internal energy changes in solution processes. Chem. Phys. 65, 239–245 (1982).

Scalmani, G. & Frisch, M. J. Continuous surface charge polarizable continuum models of solvation. I. General formalism. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 114110 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21576059 and 21666008), Fok Ying-Tong Education Foundation (161030), Guizhou Science & Technology Foundation ([2018]1037 & [2017]5788), and Key Technologies R&D Program of China (2014BAD23B01). NMR spectra were acquired at the instruments of the NMR center, DTU. S.S. gratefully thanks the Department of Biotechnology (Government of India) New Delhi, India for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L., S.S., A.R. and S.Y. conceived the research ideas and directed the overall project. H.L., W.Z. and J.H. designed and performed the experiments. W.D. made DFT calculations. S.M. collected and analyzed the NMR data. H.L., S.M., S.S. and A.R. co-wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the different versions of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Zhao, W., Saravanamurugan, S. et al. Control of selectivity in hydrosilane-promoted heterogeneous palladium-catalysed reduction of furfural and aromatic carboxides. Commun Chem 1, 32 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-018-0033-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-018-0033-z

This article is cited by

-

Room-temperature selective hydrogenation of unsaturated biomass feedstocks enabled by hydrosilane and eggshell-derived catalyst with enhanced basicity and hydrophobicity

Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery (2022)

-

F-containing ionic liquid–catalyzed benign and rapid hydrogenation of bio-based furfural and relevant aldehydes using siloxane as hydrogen source

Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery (2020)

-

Aqueous-phase hydrogenation of furfural over supported palladium catalysts: effect of the support on the reaction routes

Reaction Kinetics, Mechanisms and Catalysis (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.