China’s commitment to stop its emissions rising will require the kind of massive top-down reformation only possible in a one party state, according to analysts.

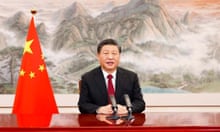

On Wednesday, Chinese president Xi Jinping stood beside his US counterpart Barack Obama to announce an “historic” deal on carbon agreed between the world’s two biggest polluters.

The US announced new emissions targets for 2025 and, for the first time officially, China said it would aim to stop emissions rising by “around 2030”. China also committed to 20% of its energy coming from wind, solar, nuclear and other zero-emission sources by 2030. But the world’s most influential country on future global warming declined to say how high the peak in emissions would be.

“We know today when we will see the summit of the mountain, but we don’t know the contour,” says Greenpeace East Asia’s senior climate and energy campaigner, Li Shuo.

The scale of change required in China makes all other countries’ seem insignificant.

In order to meet its clean energy target, between now and 2030 China will need to add 800-1000GW of clean energy - enough capacity to power the entire US. Tony Abbott’s climate sceptic government may pause to consider that China will add enough zero-emissions capacity every year to power the whole of Australia.

Analysts will now look closely at how the government backs up the international commitment in its domestic policy. The Communist party’s 13th five year plan (2016-2020) will define how the country means to achieve these goals.

Milo Sjardin, head of Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s Asia arm, says China’s stable government allows for a level of future certainty that makes massive, systemic transitions manageable and politically relevant - a key difference with the more chaotic US system.

“China is very much driven by policy and they do think very long term. Unlike the US they are not bound by 2 year electoral cycles,” he says. Sjardin believes China must now look to put a price on carbon in order to shift power generation from coal to lower emitting gas. The next five year plan could also include some measures to incentivise electric vehicles in major cities.

Li said that despite their scale, the goals are achievable, especially with the seal of Xi Jinping. “I do have confidence that they will be able to deliver this target. Xi’s signature on the statement provides some assurance.”

In terms of dealing with China’s deeply bureaucratic energy sector, the president’s aegis is vital.

China’s power supply is not dictated by markets as it is in the west, where the grid buys from the power plants that produce the cheapest energy (after subsidies). In China, state administrators dictate to operators how much power they are required to produce. Li says these decisions are governed by vested interests and heavily favour coal and gas. Xi’s influence may be the key to breaking fossil fuels’ grasp on the electricity sector.

Many in China expect a cap on coal to be included in the next five year plan. Li says this is the single most important policy measure for reducing carbon emissions. Such a cap will not only help China to bring its emissions to a peak, it will also add impetus to the already massive push for solar and wind energy.

China has already committed to reaching a 15% share of its energy from non-fossil fuel sources by 2020. This won’t be easy, says Li.

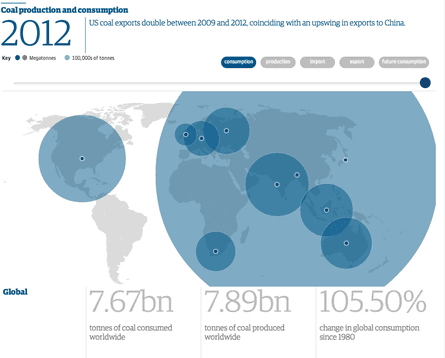

The number of Chinese driving petrol cars will explode over the next 15 years, creating a significant drag on emissions reductions. The industrial sector is similarly locked into processes that require fossil fuels - for example the use of coal in steelmaking. Sjardin says the majority of gains will need to come from the Chinese power sector. At the moment around two thirds of power is generated by coal.

But Sjardin says a 43% non-fossil fuel share of Chinese electricity generation by 2030 is “achievable”. “The Chinese power sector is going to look very different after the next 15 years than it has done in the past,” he says.

To achieve this extraordinary turnaround, China is pouring huge sums of state money into wind and solar. In 2013, China invested US$64bn in renewable energy projects. This is $2bn less that the US invested over the same period. But from almost the same amount of money China installed more than seven times more energy capacity than America. China’s money was overwhelmingly concentrated on delivering products on the ground, whereas the US was focussed on research and the development of intellectual property.

In 2013, China installed 12GW of solar outstripping all expectations and smashing records. No country had ever installed more than 8GW in a single year before 2013. By 2020, China aims to have 100GW of solar installed. China’s wind sector is similarly booming with thousands upon thousands of wind turbines to sprout across its high western deserts during the next six years. By 2020, wind capacity is expected to more than double from 75GW to 200GW.

Wednesday’s announcement will extend this trajectory. Li believes the solar and wind sectors in China are already straining and meeting the 2020 targets will be “quite challenging”. The cheapest, most effective gains are happening now. Each percentage of power generation added and emissions reduced gets more expensive.

But Sjardin says his modelling indicates that the 2020 and 2030 targets will be achievable, although this depends in large part on China’s economic growth, which is currently slower than in the past decade. A surge in growth would drive demand for energy and send China back to the coal mine.

Some observers are sceptical about China’s level of ambition. In the US, the Republicans have rallied around a line that the US committed to a big decrease in emissions but China has simply promised what would have happened anyway.

In its World Energy Outlook, also released on Wednesday, the International Energy Agency (IEA) outlined various pathways for China’s emissions.

Felix Preston, a senior research fellow at Chatham House, has analysed these and says China’s new goals represent an increase in ambition but still fall well short of a safe climate future.

“The 20% figure is higher than the 18% share in the IEA’s latest ‘new policies’ scenario, which takes account of broad policy commitments and plans that have been announced by countries. In this sense it is another ratcheting up, and builds on the existing target of 15% in 2020. However 20% is some way below the share of 26% in the more climate-secure 450 scenario,” says Preston.

The IEA’s “450 scenario”, in which the levels of atmospheric carbon stay within safe limits, China’s non-fossil energy would triple between today and 2030. The 20% target means it will double.

Another important aspect of the equation, says Preston, is what happens within the fossil fuel mix. Natural gas, while still a fossil fuel, has significantly lower emissions that coal. Under the IEA’s 450 scenario, gas use in China increases four times on current levels.

Like all Chinese policy, and the world’s future climate, these decisions now rest with China’s Politburo.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion