Scientists have had a rough year. The leaked “Climategate” e-mails painted researchers as censorious. The mild H1N1 flu outbreak led to charges that health officials exaggerated the danger to help Big Pharma sell more drugs. And Harvard University investigators found shocking holes in a star professor’s data. As policy decisions on climate, energy, health and technology loom large, it’s important to ask: How badly have recent events shaken people’s faith in science? Does the public still trust scientists?

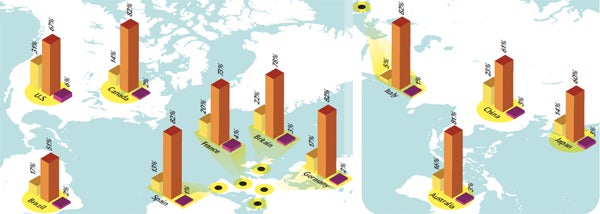

To find out, Scientific American partnered with our sister publication, Nature, the international journal of science, to poll readers online. More than 21,000 people responded via the Web sites of Nature and of Scientific American and its international editions. As expected, it was a supportive and science-literate crowd—19 percent identified themselves as Ph.Ds. But attitudes differed widely depending on particular issues—climate, evolution, technology—and on whether respondents live in the U.S., Europe or Asia.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

How Much Do People Trust What Scientists Say?

We asked respondents to rank how much they trusted various groups of people on a scale of 1 (strongly distrust) to 5 (strongly trust). Scientists came out on top by a healthy margin. When we asked how much people trust what scientists say on a topic-by-topic basis, only three topics (including, surprisingly, evolution) garnered a stronger vote of confidence than scientists did as a whole.

When Science Meets Politics: A Tale of Three Nations Should scientists get involved in politics? Readers differ widely depending on where they are from. Germany, whose top politician has a doctorate in quantum chemistry, seems to approve of scientists playing a big role in politics. Not so in China. Even though most leaders are engineers, Chinese respondents were much less keen than their German or U.S. counterparts to see scientists in political life.

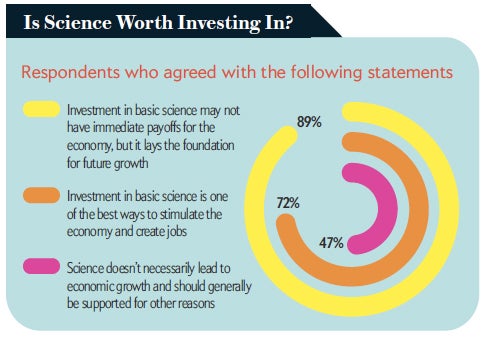

Build Labs, Not Guns

More than 70 percent of respondents agreed that in tough economic times, science funding should be spared. When asked what should be cut instead, defense spending was the overwhelming pick.

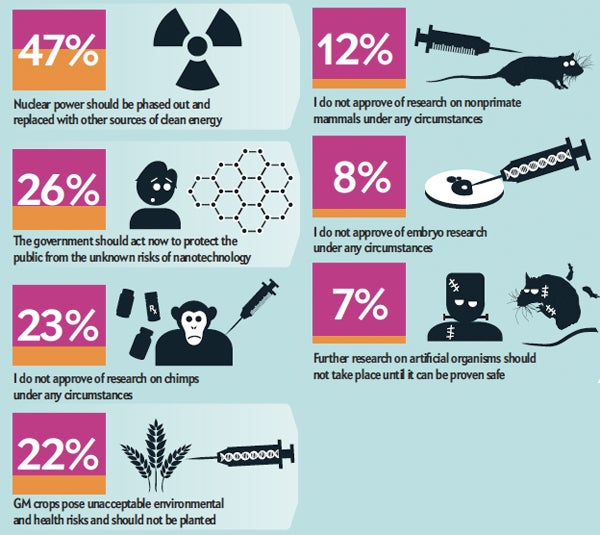

Techno Fears

Technology can lead to unintended consequences. We asked readers what technological efforts need to be reined in—or at least closely monitored. Surprisingly, more respondents were concerned about nuclear power than artificial life, stem cells or genetically modified crops.

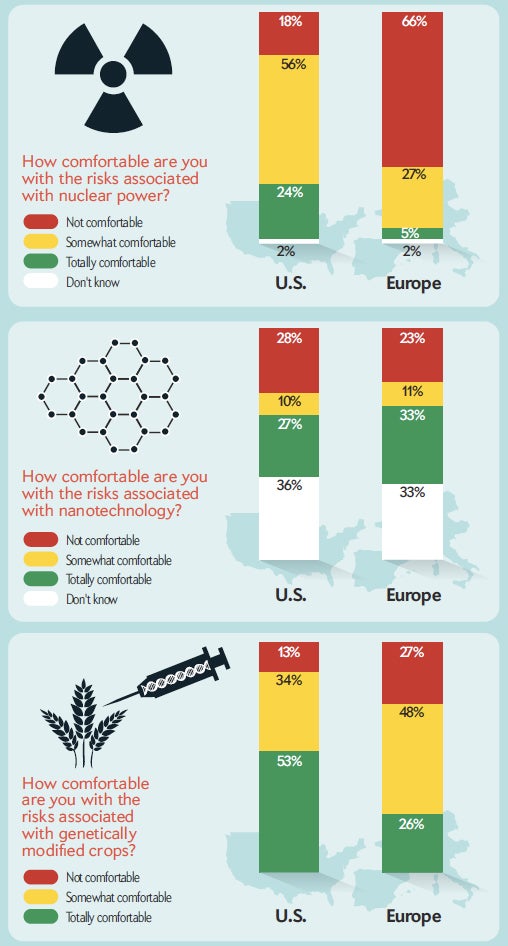

U.S. vs. Europe

Europeans and Americans differ sharply in their attitudes toward technology. Higher proportions of respondents from Europe worry about nuclear power and genetically modified crops than those from the U.S. (In this grouping, Europe includes Belgium, France, Germany, Italy and Spain, but not Britain, where opinion is more closely aligned with that of the U.S.) In both Europe and the U.S., nanotechnology seems to be a great unknown. Europeans also expressed a mistrust of what scientists have to say about flu pandemics.

Suspicion Over the Flu

On June 11, 2009, the Geneva-based World Health Organization declared the H1N1 flu outbreak a pandemic, confirming what virologists already knew—that the flu virus had spread throughout the world. Governments called up billions of dollars’ worth of vaccines and antiretroviral drugs, a medical arsenal that stood ready to combat a virus that, thankfully, turned out to be mild.

A year later two European studies charged that the WHO’s decision-making process was tainted by conflicts of interest. In 2004 a WHO committee recommended that governments stockpile antiretroviral drugs in times of pandemic; the scientists on that committee were later found to have ties to drug companies. The WHO has refused to identify the scientists who sat on last year’s committee that recommended the pandemic declaration, leading to suspicions that they might have ties to industry as well.

The controversy got a lot of press in Europe—the Daily Mail, a British tabloid, declared: “The pandemic that never was: Drug firms ‘encouraged world health body to exaggerate swine flu threat’”; the controversy in the U.S. garnered little mention.

The brouhaha seems to have influenced opinion markedly in Europe. Nearly 70 percent of U.S. respondents in our survey trusted what scientists say about flu pandemics; in Europe, only 31 percent felt the same way. The figures represented the largest split between the U.S. and Europe on any issue in the poll.

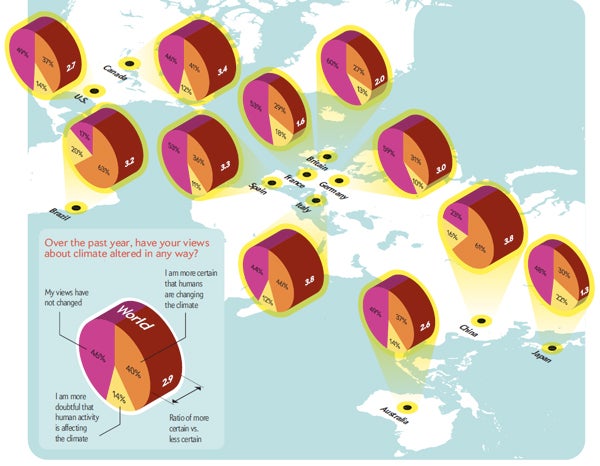

Climate Denial on the Decline

Numerous polls show a decline in the percentage of Americans who believe humans affect climate, but our survey suggests the nation is not among the worst deniers. (Those are France, Japan and Australia.) Attitudes, however, may be shifting the other way. Among those respondents who have changed their opinions in the past year, three times more said they are more certain than less certain that humans are changing the climate.