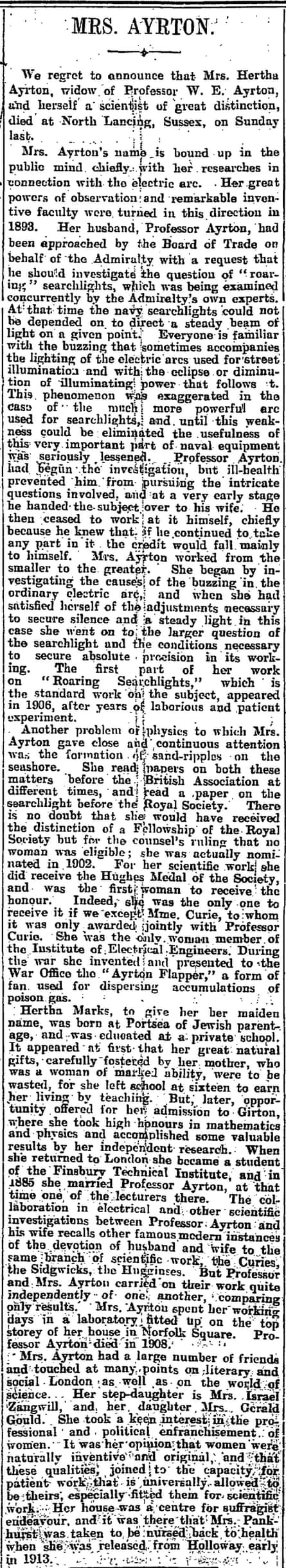

We regret to announce that Mrs. Hertha Ayrton, widow of Professor W. E. Ayrton, and herself a scientist of great distinction, died at North Lancing, Sussex, on Sunday last.

Mrs. Ayrton’s name is bound up in the public mind chiefly with her researches in connection with the electric arc. Her great powers of observation and remarkable inventive faculty were turned in this direction in 1893. Her husband, Professor Ayrton, had been approached by the Board of Trade on behalf of the Admiralty with a request that he should investigate the question of “roaring” searchlights, which was being examined concurrently by the Admiralty’s own experts.

Professor Ayrton had begun the investigation but ill-health prevented him from pursuing the intricate questions involved, and at a very early stage he handed the subject over to his wife. He then ceased to work at it himself, chiefly because he knew that if he continued to take any part in it the credit would fall mainly to himself.

Another problem of physics to which Mrs. Ayrton gave close and continuous attention was the formation of sand-ripples on the seashore. She read papers on both these matters before the British Association at different times, and read a paper on the searchlight before the Royal Society. There is no doubt that she would have received the distinction of a Fellowship of the Royal Society but for the counsel’s ruling that no woman was eligible; she was actually nominated in 1902.

For her scientific work she did receive the Hughes Medal of the Society, and was the first woman to receive the honour. Indeed, she was the only one to receive it if we except Mme. Curie, to whom it was only awarded jointly with Professor Curie. She was the only woman member of the Institute of Electrical Engineers.

Mrs Ayrton took a keen interest in the professional and political enfranchisement of women. It was her opinion that women were naturally inventive and original, and that these qualities, joined to the capacity for patient work that is universally allowed to be theirs, especially fitted them for scientific work. Her house was a centre for suffragist endeavour, and it was there that Mrs. Pankhurst was taken to be nursed back to health when she was released from Holloway early in 1913.

This is an edited extract, read the full obituary below

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion