Abstract

Malaria is caused in humans by five species of single-celled eukaryotic Plasmodium parasites (mainly Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax) that are transmitted by the bite of Anopheles spp. mosquitoes. Malaria remains one of the most serious infectious diseases; it threatens nearly half of the world's population and led to hundreds of thousands of deaths in 2015, predominantly among children in Africa. Malaria is managed through a combination of vector control approaches (such as insecticide spraying and the use of insecticide-treated bed nets) and drugs for both treatment and prevention. The widespread use of artemisinin-based combination therapies has contributed to substantial declines in the number of malaria-related deaths; however, the emergence of drug resistance threatens to reverse this progress. Advances in our understanding of the underlying molecular basis of pathogenesis have fuelled the development of new diagnostics, drugs and insecticides. Several new combination therapies are in clinical development that have efficacy against drug-resistant parasites and the potential to be used in single-dose regimens to improve compliance. This ambitious programme to eliminate malaria also includes new approaches that could yield malaria vaccines or novel vector control strategies. However, despite these achievements, a well-coordinated global effort on multiple fronts is needed if malaria elimination is to be achieved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria has had a profound effect on human lives for thousands of years and remains one of the most serious, life-threatening infectious diseases1–3. The disease is caused by protozoan pathogens of the Plasmodium spp.; Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax, for which humans are the exclusive mammalian hosts, are the most common species and are responsible for the largest public health burden. Malaria is transmitted by the bite of Plasmodium spp.-infected female mosquitoes of the Anopheles genus1–3. During a blood meal, infected mosquitoes inject — along with their anticoagulating saliva — sporozoites, which are the infective, motile stage of Plasmodium spp. Sporozoites journey through the skin to the lymphatics and into hepatocytes in the liver (Fig. 1). Inside the hepatocyte, a single sporozoite can generate tens of thousands of merozoites (the stage that results from multiple asexual fissions (schizogony) of a sporozoite within the body of the host), which are released into the bloodstream where they enter red blood cells to replicate (erythrocytic schizogony). A fraction of merozoites (those that are sexually committed) also differentiate and mature into male and female gametocytes, which is the stage that infects the mosquito host when it takes a blood meal4,5. The onset of clinical symptoms generally occurs 7–10 days after the initial mosquito bite. P. vivax and Plasmodium ovale also have dormant forms, called hypnozoites, which can emerge from the liver years after the initial infection6, leading to relapse if not treated properly.

The mosquito vector transmits the Plasmodium spp. parasite in the sporozoite stage to the host during a blood meal. Within 30–60 minutes, sporozoites invade liver cells, where they replicate and divide as merozoites. The infected liver cell ruptures, releasing the merozoites into the bloodstream, where they invade red blood cells and begin the asexual reproductive stage, which is the symptomatic stage of the disease. Symptoms develop 4–8 days after the initial red blood cell invasion. The replication cycle of the merozoites within the red blood cells lasts 36–72 hours (from red blood cell invasion to haemolysis). Thus, in synchronous infections (infections that originate from a single infectious bite), fever occurs every 36–72 hours, when the infected red blood cells lyse and release endotoxins en masse70–72. Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale can also enter a dormant state in the liver, the hypnozoite. Merozoites released from red blood cells can invade other red blood cells and continue to replicate, or in some cases, they differentiate into male or female gametocytes4,5. The transcription factor AP2-G (not shown) has been shown to regulate the commitment to gametocytogenesis. Gametocytes concentrate in skin capillaries and are then taken up by the mosquito vector in another blood meal. In the gut of the mosquito, each male gametocyte produces eight microgametes after three rounds of mitosis; the female gametocyte matures into a macrogamete. Male microgametes are motile forms with flagellae and seek the female macrogamete. The male and female gametocytes fuse, forming a diploid zygote, which elongates into an ookinete; this motile form exits from the lumen of the gut across the epithelium254 as an oocyst. Oocysts undergo cycles of replication and form sporozoites, which move from the abdomen of the mosquito to the salivary glands. Thus, 7–10 days after the mosquito feeds on blood containing gametocytes, it may be ‘armed’ and able to infect another human with Plasmodium spp. with her bite. Drugs that prevent Plasmodium spp. invasion or proliferation in the liver have prophylactic activity, drugs that block the red blood cell stage are required for the treatment of the symptomatic phase of the disease, and compounds that inhibit the formation of gametocytes or their development in the mosquito (including drugs that kill mosquitoes feeding on blood) are transmission-blocking agents. *Merozoite invasion of red blood cells can be delayed by months or years in case of hypnozoites. ‡The number of days until symptoms are evident. §The duration of gametogenesis differs by species. ||The maturation of sporozoites in the gut of the mosquito is highly temperature-dependent. Adapted with permission from Ref. 255, Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

The consequences of Plasmodium spp. infection vary in severity depending on the species and on host factors, including the level of host immunity, which is linked to the past extent of parasite exposure7,8. Malaria is usually classified as asymptomatic, uncomplicated or severe (complicated)9 (Box 1). Typical initial symptoms are low-grade fever, shaking chills, muscle aches and, in children, digestive symptoms. These symptoms can present suddenly (paroxysms), and then progress to drenching sweats, high fever and exhaustion. Malaria paroxysmal symptoms manifest after the haemolysis of Plasmodium spp.-invaded red blood cells. Severe malaria is often fatal, and presents with severe anaemia and various manifestations of multi-organ damage, which can include cerebral malaria8 (Box 1). Severe malaria complications are due to microvascular obstruction caused by the presence of red blood cell-stage parasites in capillaries8,10,11. This Primer focuses on our understanding of malaria pathology in the context of parasite and vector biology, progress in diagnostics and new treatments (drugs and vaccines), chemoprotection and chemoprevention.

Epidemiology

The vector

Human malaria parasites are transmitted exclusively by ∼40 species of the mosquito genus Anopheles12. During Anopheles spp. mating, males transfer high levels of the steroid hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone to the females, and the presence of this hormone has been associated with favourable conditions for Plasmodium spp. development13. Malaria-competent Anopheles spp. are abundant and distributed all over the globe, including the Arctic. However, the efficacy of malaria transmission depends on the vector species and, therefore, varies considerably worldwide; for example, in tropical Africa, Anopheles gambiae is a major and highly efficient vector14. The first WHO Global Malaria Eradication Programme (1955–1972) involved, in addition to chloroquine-based treatments, large-scale insecticide campaigns using dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)15. This strategy was quite effective against P. falciparum; although the mosquitoes gradually repopulated DDT-treated areas (because they developed resistance to the insecticide, and the use of DDT itself waned owing to its costs and increasing environmental concerns), these areas have often remained malaria-free and in some cases still are. More-selective vector control approaches, such as the use of insecticide-treated bed nets and indoor residual spraying, have eliminated malaria from several areas (see Diagnosis, screening and prevention, below). However, mosquito resistance to insecticides is a growing concern. Of the 78 countries that monitor mosquito resistance to insecticides, 60 have reported resistance to one or more insecticides since 2010 (Ref. 16).

The parasite

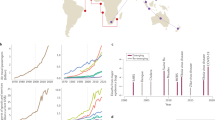

Plasmodium spp. are single-celled eukaryotic organisms17–19 that belong to the phylum Apicomplexa, which is named for the apical complex that is involved in host cell invasion. A discussion of the parasite genome and the genetic approaches used to study parasite biology is provided in Box 2. Of the five human-infective Plasmodium spp., P. falciparum causes the bulk of malaria-associated morbidity and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, with mortality peaking in the late 1990s at over 1 million deaths annually in the continent20 (Fig. 2). P. falciparum is associated with severe malaria and complications in pregnancy (Box 3); most malaria-related deaths are associated with this species, which kills ∼1,200 African children <5 years of age each day21. However, P. falciparum is also found in malarious tropical areas around the world. P. vivax is found in malarious tropical and temperate areas, primarily Southeast Asia, Ethopia and South America, and generally accounts for the majority of malaria cases in Central and South America and in temperate climates. This distribution can be explained by the fact that P. vivax can survive in climatically unfavourable regions and can stay dormant in a hypnozoite form in its human host's liver for many years. Furthermore, many Africans are negative for the Duffy antigen (also known as atypical chemokine receptor 1) on the surface of red blood cells, and this genotype provides protection from P. vivax malaria, as it makes it more difficult for P. vivax to bind to and penetrate red blood cells22. However, some cases of P. vivax transmission to Duffy antigen-negative individuals have been reported, which suggests that alternative mechanisms of invasion might be present in some strains, and this might portend the escalation of P. vivax malaria to Africa23,24. P. ovale is also found in Africa and Asia, but is especially prevalent in West Africa. Two sympatric species exist: P.o. curtisi and P.o. wallikeri25. Plasmodium malariae — which can be found worldwide but is especially prevalent in West Africa — causes the mildest infections, although it has been associated with splenomegaly or renal damage upon chronic infection. Plasmodium knowlesi — which was initially considered as a parasite of non-human primates — can not only cause malaria in humans but can also lead to severe and even fatal malaria complications26,27. The reasons for the emergence of P. knowlesi in humans are not yet fully understood but are possibly linked to land-use changes that have brought humans into close contact with P. knowlesi-infected mosquitoes28. Regardless, the possible recent emergence of a form of malaria as a zoonosis poses obvious complications for elimination. In addition, co-infections between P. falciparum and P. vivax have been well-documented and have been reported to occur in up to 10–30% of patients living in areas where both parasites are prevalent29,30. Mixed infections can also include other species such as P. ovale and P. malariae, and newer diagnostic methods are being developed that will enable better assessment of the frequency and distribution of these types of co-infection (for example, Ref. 31).

The most-deadly malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, is only found in tropical areas because its gametocytes require 10–18 days at a temperature of >21°C to mate and mature into infectious sporozoites inside the vector256. This development timeline is only possible in hot, tropical conditions; where the ambient temperature is lower, mosquitoes can still propagate, but sporozoite maturation is slowed down and, therefore, incomplete, and parasites perish without progeny when the mosquitoes die. Thus, P. falciparum is quite temperature-sensitive; a global temperature rise of 2–3 °C might result in an additional 5% of the world population (that is, several hundred million people) being exposed to malaria257. Of note, Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale can develop in mosquitoes at ambient temperatures as low as 16 °C. The abilities of these parasites to propagate at subtropical temperatures and to remain in the hypnozoite state in the liver are likely to explain their ability to survive dry or cold seasons, and the broader global distribution of these parasites258. Countries coded ‘not applicable’ in the Figure were not separately surveyed. Figure based on data from Ref. 16, WHO.

The disease

Malaria remains a major burden to people residing in resource-limited areas in Africa, Asia and Central and South America (Fig. 2). An estimated 214 million cases of malaria occurred in 2015 (Ref. 16). Africa bears the brunt of the burden, with 88% of the cases, followed by Southeast Asia (10%), the eastern Mediterranean region (2%) and Central and South America (<1%). Malaria continues to kill over three-times as many people as all armed conflicts; in 2015, there were an estimated 438,000 (Ref. 16) — 631,000 (Ref. 20) deaths resulting from malaria, compared with an estimated 167,000 deaths due to armed conflicts32,33. In areas of continuous transmission of malaria, children <5 years of age and the fetuses of infected pregnant women experience the most morbidity and mortality from the disease. Children >6 months of age are particularly susceptible because they have lost their maternal antibodies but have not yet developed protective immunity. In fact, adults and children >5 years of age who live in regions of year-round P. falciparum transmission develop a partial protective immunity owing to repeated exposure to the parasite. There is evidence that immunity against P. vivax is acquired more quickly34. Individuals with low protective immunity against P. falciparum are particularly vulnerable to severe malaria. Severe malaria occurs in only 1% of infections in African children and is more common in patients who lack strong immune protection (for example, individuals who live in low-transmission settings, children <5 years of age and naive hosts). Severe malaria is deadly in 10% of children and 20% of adults7. Pregnant women are more susceptible to Plasmodium spp. infection because the placenta itself selects for the emergence of parasites that express receptors that recognize the placental vasculature; these receptors are antigens to which pregnant women have not yet become partially immune7 (Box 3). This vulnerability increases the risk of miscarriage; parasitaemia in the placenta can have adverse effects on the fetus35–37 (Box 3).

Co-infection of Plasmodium spp. with other pathogens — including HIV, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and helminths — is common. HIV-infected adults are at an increased risk of severe malaria and death38. The overall prevalence of helminth infection is very high (>50% of the population) in malaria-endemic regions and is associated with increased malaria parasitaemia39. Surprisingly, naturally occurring iron deficiency and anaemia protect against severe malaria, which was an unexpected finding40, as numerous clinical studies have aimed to fortify children and prevent anaemia by distributing iron supplements41.

From 2000 to 2015, the incidence of malaria fell by 37% and the malaria mortality rate fell by 60% globally16. The WHO attributes much of this reduction of malaria-associated morbidity and mortality to the scale-up of three interventions: insecticide-treated bed nets (69% of the reduction), artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs; 21%) and indoor residual insecticide spraying (10%)16 (see Diagnosis, screening and prevention, below). Until ACT was introduced, progress in malaria control in most malarious countries was threatened or reversed by the nearly worldwide emergence of chloroquine-resistant and sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine-resistant P. falciparum strains and, more recently, of other resistant Plasmodium spp. ACT has become the antimalarial medicine of choice in most malarious areas, and demonstrates rapid parasite clearance, superior efficacy (compared with other clinically approved drugs) and >98% cure rates (typically defined as the percentage of patients who remain malaria-free for 28 days; re-infection events do not count as a recurrence). ACTs achieve these results even in strains that are resistant to older antimalarials, effectively turning the tide against antimalarial drug resistance. However, the emergence of artemisinin-resistant strains in Southeast Asia threatens the usefulness of ACTs42–45 (see Drug resistance, below).

Mechanisms/pathophysiology

The red blood cell stage

As previously mentioned, the red blood cell stage of Plasmodium spp. infection is the cause of symptomatic malaria, as red blood cells are the site of abundant parasite replication.

Invasion. Plasmodium spp. parasites gain entry into the red blood cell through specific ligand–receptor interactions mediated by proteins on the surface of the parasite that interact with receptors on the host erythrocyte (mature red blood cell) or reticulocyte (immature red blood cell)46 (Fig. 3). Whereas P. falciparum can invade and replicate in erythrocytes and reticulocytes, P. vivax and other species predominantly invade reticulocytes, which are less abundant than erythrocytes47. Most of the parasite erythrocyte-binding proteins or reticulocyte-binding proteins that have been associated with invasion are redundant or are expressed as a family of variant forms; however, for P. falciparum, two essential red blood cell receptors (basigin and complement decay-accelerating factor (also known as CD55)) have been identified (Fig. 3).

Invasion occurs through a multistep process259. During pre-invasion, low-affinity contacts are formed with the red blood cell membrane. Reorientation of the merozoite is necessary to enable close contact between parasite ligands and host cell receptors, and this is then followed by tight junction formation. In Plasmodium falciparum, a forward genetic screen has shown that complement decay-accelerating factor (not shown) on the host red blood cell is essential for the invasion of all P. falciparum strains260. The interaction of a complex of P. falciparum proteins (reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 5 (PfRH5), PfRH5-interacting protein (PfRipr) and cysteine-rich protective antigen (PfCyRPA)) with basigin on the red blood cell surface is also essential for the invasion in all strains261,262. PfRH5 has been studied as a potential vaccine candidate46, and antibodies against basigin have been considered as a potential therapeutic strategy263. During the PfRH5–PfRipr–PfCyRPA–basigin binding step, an opening forms between the parasite and the red blood cell, and this triggers Ca2+ release and enables parasite-released proteins to be inserted into the red blood cell membrane. These proteins are secreted from the micronemes (the small secretory organelles that cluster at the apical end of the merozoite) and from the neck of the rhoptries, and include rhoptry neck protein 2 (PfRON2). Binding between PfRON2 and apical membrane antigen 1 (PfAMA1) on the merozoite surface is required to mediate tight junction formation before the internalization process264, and PfAMA1 is also being evaluated as a vaccine candidate265. Parasite replication within the red blood cell requires the synthesis of DNA, which can be blocked by several antimalarials: pyrimethamine (PYR), P218 and cycloguanil target P. falciparum dihydrofolate reductase (PfDHFR)266, and atovaquone (ATO) blocks pyrimidine biosynthesis by inhibiting the expression of the mitochondrial gene pfcytb (which encodes P. falciparum cytochrome b) and by preventing the formation of oxidized coenzyme Q, which is needed to enable the pyrimidine biosynthetic enzyme dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (PfDHODH) to perform its reaction within the mitochondria50. The phase II clinical candidate DSM265 also blocks pyrimidine biosynthesis by directly inhibiting PfDHODH186. In addition to DNA synthesis, other processes can be targeted by antimalarial drugs. Chloroquine (CHQ) inhibits haem polymerization in the food vacuole52 but can be expelled from this compartment by the P. falciparum chloroquine-resistance transporter (PfCRT)267. The phase II clinical candidate KAE609 and the preclinical candidate SJ(557)733 both inhibit P. falciparum p-type ATPase 4 (PfATP4), which is required for Na+ homeostasis during nutrient acquisition57,183,184. The phase I clinical candidate MMV(390)048 (Ref. 191) inhibits P. falciparum phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PfPI(4)K), which is required for the generation of transport vesicles that are needed to promote membrane alterations during ingression58. Hb, haemoglobin.

Replication. Once Plasmodium spp. gain entry into the red blood cell, they export hundreds of proteins into the host cell cytoplasm and cell surface that modulate the acquisition of nutrients, cell adhesion and sequestration in tissues, and pathogenesis3,48,49. Molecular and cell biology approaches are expanding our understanding of the molecular machinery that is required for the export, as well as the identification and function of the exported proteins.

In the red blood cell, Plasmodium spp. replicate rapidly, and during symptomatic disease the parasites may replicate exponentially to >1012 parasites per patient. This rapid growth requires sustained pools of nucleotides for the synthesis of DNA and RNA, and as a consequence, many antimalarials target pyrimidine biosynthesis50 (Fig. 3). Plasmodium spp. are auxotrophic for all of the amino acids they need (that is, they must acquire all of these from food because they cannot synthesize them from precursors). Haemoglobin digestion (in a specialized food vacuole) supplies all amino acids except isoleucine, which must be obtained from other host cell components51. Haemoglobin digestion also releases haem, which is toxic to the parasite and, therefore, is polymerized into haemozoin (often called malaria pigment, which is visible as a blue pigment under light microscopy), which is an insoluble crystal that sequesters the toxic metabolite52. How haem polymerization is facilitated by the parasite remains unclear. A complex of several proteases and haem detoxification protein (HDP) have been identified in the food vacuole; follow-up in vitro studies have shown that components of this complex (for example, falcipain 2, HDP and lipids) were able to catalyse the conversion of haem into haemozoin53. The importance of understanding this mechanism is highlighted by the finding that chloroquine and other antimalarials act by inhibiting haem polymerization54 (Fig. 3). There is also evidence that the iron (haem-bound or free) liberated in the food vacuole during haemoglobin digestion plays a part in activating the toxicity to the parasite of artemisinin derivatives42.

Nutrient uptake by the parasite is coupled to the detrimental accumulation of Na+; however, the parasite expresses an essential plasma membrane Na+ export pump (the cation ATPase P. falciparum p-type ATPase 4 (PfATP4)) that can maintain Na+ homeostasis55–57 (Fig. 3). The remodelling of the plasma membrane (membrane ingression) to generate daughter merozoites in the late schizont stage requires P. falciparum phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PfPI(4)K)58. Both PfPI(4)K and PfATP4 are targets of new drugs that are under development (Fig. 3).

Immune evasion and host immunity

Malaria parasites first encounter the host immune system when sporozoites are injected in the skin (measured to be ∼15 per mosquito bite in one study59), where they may be phagocytosed by dendritic cells for antigen presentation in the lymph node draining the skin inoculation site60. The chances of transmission are increased when the host is bitten by mosquitoes that carry a larger number of sporozoites, despite the fact that the number of sporozoites that can simultaneously pass through the mosquito's proximal duct is limited by the duct diameter61. Sporozoites encounter several other effectors of the immune system, and how a minority of them can reach the liver and infect the hepatocytes is not well understood. Immune evasion in the liver could be in part explained by the ability of sporozoites to suppress the function of Kupffer cells (also known as stellate macrophages, which are the resident macrophages of the liver) and repress the expression of genes that encode MHC class I molecules62. Our understanding of the host immunity associated with the red blood cell stage is more complete. Virulence genes in Plasmodium spp. are part of large expanded multigene families that are found in specialized (for example, subtelomeric) regions of the chromosomes7,63,64. These gene families (for example, var genes in P. falciparum) encode variants of cell surface proteins that function in immune evasion through antigenic variation and also are involved in mediating cytoadherence of infected red blood cells to endothelial cells, which leads to red blood cell sequestration in tissues.

Malaria disease severity — in terms of both parasite burden and the risk of complicated malaria — is dependent on the levels of protective immunity acquired by the human host65–67, which can help to decrease the severity of symptoms and reduce the risk of severe malaria. Immunity is thought to result from circulating IgG antibodies against surface proteins on sporozoites (thereby blocking hepatocyte invasion) and merozoites (thereby blocking red blood cell invasion). In high-transmission areas where malaria is prevalent year-round, adults develop partially protective immunity. Young infants (<6 months of age) are also afforded some protection, probably from the antibodies acquired from their mother, whereas children from 6 months to 5 years of age have the lowest levels of protective immunity and are the most susceptible to developing high parasitaemia with risks for complications and death (for example, see the study conducted in Kilifi, Kenya68). In low-transmission areas or areas that have seasonal malaria, individuals develop lower levels of protective immunity and typically have worse symptomatic malaria upon infection. This correlation between protective immunity and malaria severity poses a challenge for successful malaria treatment programmes; as the number of infections and the transmission rates decrease, increasing numbers of patients will lose protective immunity and become susceptible to severe disease. The re-introduction of malaria in areas that had been malaria-free for many years could be devastating in the short term and, therefore, well-organized surveillance is required.

Pathogenesis

The predominant pathogenic mechanism is the haemolysis of Plasmodium spp.-infected red blood cells, which release parasites and malaria endotoxin — understood to be a complex of haemozoin and parasite DNA, which trigger Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), a nucleotide-sensing receptor involved in the host immune response against pathogens69 — that leads to high levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) production and to clinical symptoms such as fever70–72. In addition, the membrane of infected red blood cells stiffens, and this loss of deformability contributes to the obstruction of capillaries, which has life-threatening consequences in severe malaria when vital organs are affected73.

Parasite factors that influence disease severity. Disease severity and pathogenesis are linked to surface proteins that are expressed by the parasite. In P. falciparum, a major surface antigen is encoded by the var gene family, which contains ∼60 members7,11,63,64. The majority of the var genes are classified into three subfamilies — A, B and C — on the basis of their genomic location and sequence: the B and C groups mediate binding to host cells via CD36 (also known as platelet glycoprotein 4), whereas the A group genes mediate non-CD36 binding interactions that have been linked to severe malaria, including cerebral malaria7,64. The var genes encode P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1), with the B and C groups accounting for >80% of PfEMP1 variants. PfEMP1 is the major protein involved in cytoadherence and mediates the binding of infected erythrocytes to the endothelial vasculature. In cerebral malaria, A group PfEMP1 variants mediate the binding of infected erythrocytes to endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR) and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) in the brain, causing pathology8,11,74,75. However, our knowledge of the host cell receptors that are involved in interactions with the infected erythrocytes is probably incomplete. For example, thrombin — which regulates blood coagulation via vitamin K-dependent protein C — can cleave PfEMP1, thereby reversing and preventing the endothelial binding of infected erythrocytes74. In pregnancy, the expression of a specific PfEMP1 variant, variant surface antigen 2-CSA (VAR2CSA) — which is not encoded by one of the three main subfamilies — leads to an increased risk of placental malaria7,64 (Box 3).

High parasitaemia levels also seem to correlate with poor outcomes7,75, and the circulating levels of P. falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 (which is encoded by pfhrp2) have been used as a biomarker of parasitaemia that predicts the risks for microvascular obstruction and severe disease76. The brain pathology in children with severe malaria has recently been described in detail77.

Additionally, P. vivax does not express the same family of var genes that have been found to be strongly associated with endothelium binding and tissue sequestration, which drives severe disease in P. falciparum, and the ability of P. vivax to only invade reticulocytes leads to lower parasite levels7.

Host traits that influence disease severity. Malaria has exerted a strong selection pressure on the evolution of the human genome78,79. Some haemoglobin-encoding alleles that in homozygous genotypes cause severe blood disorders (such as thalassaemia, the earliest described example, and sickle cell disease) have been positively selected in populations living in malaria-endemic areas because heterozygous genotypes protect against malaria80. Other inherited haemoglobin abnormalities (for example, mutations affecting haemoglobin C and haemoglobin E) can also provide protection against malaria81.

In addition, genetic polymorphisms that affect proteins expressed by red blood cells or that lead to enzyme deficiencies can also be protective against severe disease. The red blood cell Duffy antigen is a key receptor that mediates the invasion of P. vivax through interaction with the Duffy antigen-binding protein on the parasite surface46. The genetic inheritance of mutations in ACKR1 (which encodes the Duffy antigen) in Africa is credited with reducing the spread of P. vivax in this continent, although the finding of Duffy antigen-negative individuals who can be infected with P. vivax suggests that we still have an incomplete understanding of the factors involved in P. vivax invasion82,83. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency78,79 provides protection against severe malaria through an unknown mechanism, at least in hemizygous males84, but unfortunately also leads to haemolytic anaemia in patients treated with primaquine, which is an 8-aminoquinoline antimalarial and the only agent currently approved for the treatment of latent (liver-stage) P. vivax malaria. The mode of action of primaquine, which is a prodrug, remains unknown.

The mechanisms of malaria protection in these varied genetic disorders have been widely studied81. Common findings include increased phagocytosis and elimination by the spleen of infected mutant erythrocytes, which reduces parasitaemia; reduced parasite invasion of mutant red blood cells; reduced intracellular growth rates; and reduced cytoadherence of infected mutant red blood cells. All of these effects increase protection against severe malaria, which is the main driver of human evolution in this case. Some point mutations in the gene that encodes haemoglobin alter the display of PfEMP1 on the surface of infected red blood cells, thereby diminishing cytoadherence to endothelial cells85,86. This finding highlights the crucial role of cytoadherence in promoting severe disease.

Finally, variability in the response to TNF, which is secreted from almost all tissues in response to malaria endotoxins, has also been proposed as a factor that mediates differential host responses and contributes to severe malaria when levels are high7.

Diagnosis, screening and prevention

Diagnosis

The WHO criteria for the diagnosis of malaria consider two key aspects of the disease pathology: fever and the presence of parasites87. Parasites can be detected upon light microscopic examination of a blood smear (Fig. 4) or by a rapid diagnostic test (RDT)87. The patient's risk of exposure (for example, whether the patient lives in an endemic region or their travel history) can assist in making the diagnosis. Furthermore, the clinical expression of Plasmodium spp. infection correlates with the species’ level of transmission in the area. The symptoms of uncomplicated malaria include sustained episodes of high fever (Box 1); when high levels of parasitaemia are reached, several life-threatening complications might occur (severe malaria) (Box 1).

Thin blood films showing Plasmodium falciparum (upper panel) and Plasmodium vivax (lower panel) at different stages of blood-stage development. The images are from methanol-fixed thin films that were stained for 30 minutes in 5% Giemsa. The samples were taken from Thai and Korean patients with malaria: Ethical Review Committee for Research in Human Subjects, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand (reference no. 4/2549, 6 February 2006). The sex symbols represent microgametes (male symbol) and macrogametes (female symbol). ER, early ring stage; ES, early schizont stage; ET, early trophozoite stage; FM, free merozoites; LR, late ring stage; LS, late schizont stage; LT, late trophozoite stage; U, uninfected red blood cell. The slides used were from a previously published study268 but the images shown have not been previously published. Images courtesy of A.-R. Eruera and B. Russell, University of Otago, New Zealand.

The complications of severe malaria mostly relate to the blocking of blood vessels by infected red blood cells, with the severity and symptoms depending on what organ is affected (Box 1) and to what extent, and differ by age; lung and kidney disease are unusual in children in Africa but are common in non-immune adults.

Parasitaemia. Patients with uncomplicated malaria typically have parasitaemia in the range of 1,000–50,000 parasites per microlitre of blood (however, non-immune travellers and young children who have parasite numbers <1,000 can also present with symptoms). The higher numbers tend to be associated with severe malaria, but the correlation is imprecise and there is no cut-off density. In a pooled analysis of patient data from 61 studies that were designed to measure the efficacy of ACTs (throughout 1998–2012), parasitaemia averaged ∼4,000 parasites per microlitre in South America, ∼10,000 parasites per microlitre in Asia and ∼20,000 parasites per microlitre in Africa88. The limit of detection by thick-smear microscopy is ∼50 parasites per microlitre89. WHO-validated RDTs can detect 50–1,000 parasites per microlitre with high specificity, but many lack sensitivity, especially when compared with PCR-based methods90. The ability to detect low levels of parasitaemia is important for predicting clinical relapses, as parasitaemia can increase 20-fold over a 48-hour cycle period. These data are based on measurements in healthy volunteers (controlled human infection models) who were infected at a defined time point with a known number or parasites, and in whom the asymptomatic parasite reproduction was monitored by quantitative PCR up to the point at which the individual received rescue treatment91.

In hyperendemic areas (with year-round disease transmission), often many children and adults are asymptomatic carriers of the parasite. In these individuals, the immune system maintains parasites at equilibrium levels in a ‘tug-of-war’. However, parasitaemia in asymptomatic carriers can be extremely high, with reports of levels as high as 50,000 parasites per microlitre in a study of asymptomatic pregnant women (range: 80–55,400 parasites per microlitre)92. In addition to the obvious risks for such people, they represent a reservoir for infecting mosquitoes, leading to continued transmission. In clinical studies, the parasitaemia of asymptomatic carriers can be monitored using PCR-based methods, which can detect as few as 22 parasites per millilitre93. However, the detection of low-level parasitaemia in low-resource settings requires advanced technology. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)94 is one promising approach. This type of PCR is fast (109-fold amplification in 1 hour) and does not require thermal cycling, which reduces the requirement for expensive hardware. Versions of this method that do not require electricity are being developed95. Nucleic acid-based techniques such as LAMP and PCR-based methods also have the advantage that they can be used to detect multiple pathogens simultaneously and, in theory, identify drug-resistant strains96. This approach enables the accurate diagnosis of which Plasmodium spp. is involved, and in the future could lead to the development of multiplexed diagnostics that enable differential diagnosis of the causative pathogens (including bacteria and viruses) in patients who present with fever97.

RDTs. RDTs are based on the immunological detection of parasite antigens (such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) or histidine-rich protein 2) in the blood, have sensitivities comparable to that of light microscopy examination and have the advantage that they do not require extensive training of the user. These tests provide rapid diagnosis at a point-of-care level in resource-limited settings and can, therefore, substantially improve malaria control. However, occasionally, false-positive results from RDTs can be problematic because they could lead to the wrong perception that antimalarial medicines are ineffective. False-negative test results have been reportedly caused by pfhrp2 gene deletions in P. falciparum strains in South America98–103. Current data indicate that LDH-targeting RDTs are less sensitive for P. vivax than for P. falciparum104, and limited information on the sensitivity of these tests for the rarer species, such as P. ovale or P. malariae, is available. RDTs also offer a great opportunity to track malaria epidemiology; photos taken with mobile phones of the results of the tests can be uploaded to databases (even using cloud-based data architecture105) and provide an automated collection of surveillance data106.

Prevention in vulnerable populations

The prevention of Plasmodium spp. infection can be accomplished by different means: vector control, chemoprevention and vaccines. Mosquito (vector) control methods include the following (from the broadest to the most targeted): the widespread use of insecticides, such as DDT campaigns; the use of larvicides; the destruction of breeding grounds (that is, draining marshes and other breeding reservoirs); indoor residual spraying with insecticides (that is, the application of residual insecticide inside dwellings, on walls, curtains or other surfaces); and the use of insecticide-treated bed nets. The use of endectocides has also been proposed; these drugs, such as ivermectin, kill or reduce the lifespan of mosquitoes that feed on individuals who have taken them107. However, this approach is still experimental; individuals would be taking drugs that have no direct benefit to themselves (as they do not directly prevent human illness), and so the level of safety data required for the registration of endectocides for this purpose will need to be substantial. Vector control approaches differ in terms of their efficacy, costs and the extent of their effect on the environment. Targeted approaches such as insecticide-treated bed nets have had a strong effect. Chemoprevention is an effective strategy that has been used to reduce malaria incidence in campaigns of seasonal malaria chemoprevention, in intermittent preventive treatment for children and pregnant women, and for mass drug administration108. Such antimalarials need to have an excellent safety profile as they are given to large numbers of healthy people. Vaccines excel in eradicating disease, but effective malaria vaccines are challenging because — unlike viruses and bacteria, against which effective vaccines have been developed — protist pathogens (such as Plasmodium spp.) are large-genome microorganisms that have evolved highly effective immune evasion strategies (such as encoding dozens or hundreds of cell surface protein variants). Nevertheless, the improved biotechnological arsenal to generate antigens and improved adjuvants could help to overcome these issues.

Vector control measures. The eradication of mosquitoes is no longer considered an option to eliminate malaria; however, changing the capacity of the vector reservoir has substantial effects on malaria incidence. Long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets and indoor residual spraying have been calculated to be responsible for two-thirds of the malaria cases averted in Africa between 2000 and 2015 (Ref. 12). Today's favoured and more-focused vector control approach involves the use of fine-mazed, sturdy, long-lasting and wash-proof insecticide-treated bed nets109. The fabric of these nets is impregnated with an insecticide that maintains its efficacy after ≥20 standardized laboratory washes, and these nets have a 3-year recommended use. Insects are attracted by the person below the net but are killed as they touch the net. However, the efficacy of bed nets is threatened by several factors, including their inappropriate use (for example, for fishing purposes) and behavioural changes in the mosquitoes, which have also begun to bite during the day110. The main problem, however, is the increasing emergence of vector resistance to insecticides, especially pyrethroids110 and, therefore, new insecticides with different modes of action are urgently needed. New insecticides have been identified by screening millions of compounds from the libraries of agrochemical companies, but even those at the most advanced stages of development are still 5–7 years from deployment (see the International Vector Control Consortium website (http://www.ivcc.com) and Ref. 111) (Fig. 5). Few of these new insecticides are suitable for application in bed nets (because of high costs or unfavourable chemical properties), but some can be used for indoor residual spraying. New ways of deploying these molecules are also being developed, such as improved spraying technologies112, timed release to coincide with seasonal transmission and slow-release polymer-based wall linings113,114.

The categories of compounds that are currently under study are defined in the first column on the left; compounds belonging to these categories have advanced to phase I trials or later stages. New screening hits (developed by Syngenta, Bayer, Sumitomo and the Innovative Vector Control Consortium (IVCC)) are at early research stages and are not expected to be deployed until 2020–2022. Similarly, species-specific approaches to the biological control of mosquitoes are not expected to move forward before 2025. The main data source for this Figure was the IVCC; for the latest updates visit the IVCC website (www.ivcc.com). Note that not all compounds listed on the IVCC website are shown in this Figure. The dates reflect the expected deployment dates. AI, active ingredient; CS, capsule suspension; IRS, indoor residual spray; LLIN, long-lasting insecticidal mosquito net; LLIRS, long-lasting indoor residual spray; LSHTM, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (UK); PAMVERC, Pan-African Malaria Vector Research Consortium. *Clothianidin and chlorfenapyr.

Genetic approaches, fuelled by advances in the CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing technology, represent an exciting area of development for novel insect control strategies. There are currently two main approaches: population suppression, whereby mosquitoes are modified so that any progeny are sterile; and population alteration, whereby mosquitoes are modified so that the progeny are refractory to Plasmodium spp. infection115,116. Initial approaches to population suppression involved releasing sterile male insects117. These strategies have now been developed further, with the release of male insects carrying a dominant lethal gene that kills their progeny118,119. Gene drive systems can be used for both population suppression and population alteration. These systems use homing endonucleases, which are microbial enzymes that induce the lateral transfer of an intervening DNA sequence and can, therefore, convert a heterozygote individual into a homozygote. Homing endonucleases have been re-engineered to recognize mosquito genes120 and can rapidly increase the frequency of desirable traits in a mosquito population121. Gene drive systems have now been used in feasibility studies to reduce the size of mosquito populations122 or to make mosquitoes less able to transmit malaria-causing parasites123. Another approach is inspired by the finding that Aedes aegypti mosquitoes (the vector for Dengue, yellow fever and Zika viruses) infected with bacteria of the Wolbachia spp. (a parasite that naturally colonizes numerous species of insects) cannot transmit the Dengue virus to human hosts124. Symbiont Wolbachia spp. can be modified to make them deleterious to other parasites in the same host, and progress has been made in finding symbionts that can colonize Anopheles spp. mosquitoes125,126. Although all of the above approaches are very promising, they are still at a very early stage, and the environmental uncertainties associated with the widespread distribution of such technologies, as well as the complex regulatory requirements, provide additional hurdles that will need to be overcome.

Chemoprotection and chemoprevention. Chemoprotection describes the use of medicines (given at prophylactic doses) to temporarily protect subjects entering an area of high endemicity — historically, tourists and military personnel — and populations at risk from emergent epidemics, but is also being increasingly considered for individuals visiting areas that have recently become malaria-free. Chemoprevention, which is often used in the context of seasonal malaria, describes the use of medicines with demonstrated efficacy that are given regularly to large populations at full treatment doses (as some of the individuals treated will be asymptomatic carriers).

Currently, there are three ‘gold-standard’ alternatives for chemoprotection: daily atovaquone–proguanil, daily doxycycline and weekly mefloquine. Mefloquine is the current mainstay drug used to prevent the spread of multidrug-resistant Plasmodium spp. in the Greater Mekong subregion of Southeast Asia, despite having a ‘black box warning’ for psychiatric adverse events; however, an analysis of pooled data from 20,000 well-studied patients found that this risk was small (<12 cases per 10,000 treatments)127. An active search to find new medicines that could be useful in chemoprotection, in particular medicines that can be given weekly or even less frequently, is underway. One interesting possibility is the use of long-acting injectable intramuscular combination chemoprotectants, which, if effective, could easily compete with vaccination, if they provided protection with 3–4 injections per year. Such an approach (called pre-exposure prophylaxis) is being studied for HIV infection (which also poses major challenges to the development of an effective vaccine)128 and may lead to the development of long-acting injectable drug formulations129 produced as crystalline nanoparticles (to enhance water solubility) using the milling technique.

Chemoprevention generally refers to seasonal malaria chemoprevention campaigns, which target children <5 years of age130. In the Sahel region (the area just south of the Sahara Desert, where there are seasonal rains and a recurrent threat of malaria), seasonal malaria chemoprevention with a combination of sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine plus amodiaquine had a strong effect131–135, with a >80% reduction in the number of malaria cases among children and a >50% reduction in mortality136. Although these campaigns are operationally complex — as the treatment has to be given monthly — >20 million children have been protected between 2015 and 2016, at a cost of ∼US$1 per treatment. A concern about seasonal malaria chemoprevention is the potential for a rebound effect of the disease. Rebound could occur if children lose immunity to malaria while receiving treatment that is later stopped because they reached the age limit, if campaigns are interrupted because of economic difficulties or social unrest (war), or if drug resistance develops. Owing to the presence of resistant strains, a different approach is needed in African areas south of the Equator137, and this led to trials of monthly 3-day courses of ACTs in seasonal chemoprevention135; there is an increasing amount of literature on the impressive efficacy of dihydroartemisinin (DHA)–piperaquine to prevent malaria in high-risk groups138. To reduce the potential for the emergence of drug resistance, the WHO good practice standards state that, when possible, drugs used for chemoprevention should differ from the front-line treatment that is used in the same country or region108, which emphasizes the need for the development of multiple, new and diverse treatments to provide a wider range of options.

Finally, intermittent preventive treatment is also recommended to protect pregnant women in all malaria-endemic areas108 (Box 3).

Vaccines. Malaria, along with tuberculosis and HIV infection, is a disease in which all components of the immune response (both cellular, in particular, during the liver stage, and humoral, during the blood stage) are involved yet provide only partial protection, which means that developing an effective vaccine will be a challenge. The fact that adults living in high-transmission malarious areas acquire partial protective immunity indicates that vaccination is a possibility. As a consequence, parasite proteins targeted by natural immunity, such as the circumsporozoite protein (the most prominent surface antigen expressed by sporozoites), proteins expressed by merozoites and parasite antigens exposed on the surface of infected red blood cells139 have been studied for their potential to be used in vaccine programmes140. However, experimental malaria vaccines tend to target specific parasite species and surface proteins, an approach that both restricts their use and provides scope for the emergence of resistance. Sustained exposure to malaria is needed to maintain natural protective immunity, which is otherwise lost within 3–5 years141, perhaps as a result of the clearance of circulating antibodies and the failure of memory B cells to develop into long-lived plasma B cells. Controlled human infection models142–144 have started to provide a more precise understanding of the early cytokine and T cell responses in naive subjects, emphasizing the role of regulatory T cells in dampening the response against the parasite, which results in the exhaustion of T cells145. Vaccine development is currently focusing on using multiple antigens from different stages of the parasite life cycle. Future work will also need to focus on the nature of the immune response in humans and specifically the factors that lead to diminished T cell responses. New generations of adjuvants are needed, possibly compounds that produce the desired specific response rather than inducing general immune stimulation. This is a challenging area of research, as adjuvants often have a completely different efficacy in humans compared with in preclinical animal models.

Currently, there is no vaccine deployed against malaria. The ideal vaccine should protect against both P. falciparum and P. vivax, with a protective, lasting efficacy of at least 75%. The most advanced candidate is RTS,S (trade name: Mosquirix; developed by GlaxoSmithKline and the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health Malaria Vaccine Initiative), which contains a recombinant protein with parts of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein combined with the hepatitis B virus surface antigen and a proprietary adjuvant. RTS,S reduced the number of malaria cases by half in 4,358 children 5–17 months of age during the first year following vaccination146, preventing 1,774 cases for every 1,000 children also owing to herd immunity, and had an efficacy of 40% over the entire 48 months of follow-up in children who received four vaccine doses over a 4-year period147. The efficacy of RTS,S during the entire follow-up period dropped to 26% when children only received three vaccine doses. The efficacy during the first year in 6–12-week-old children was limited to 33%. Thus, the RTS,S vaccine failed to provide long-term protection. Further studies, as requested by the WHO, will be done in pilot implementations of 720,000 children in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi (240,000 in each country, half of whom will receive the vaccine) before a final policy recommendation is made. However, a vaccine with only partial and short-term efficacy could still be used in the fight against malaria. RTS,S could be combined with chemoprevention to interrupt malaria transmission in low-endemic areas148. Thus, vaccines that are unable to prevent Plasmodium spp. infection could be used to prevent transmission (for example, by targeting gametocytes) or used as an additional protective measure in pregnant women.

A large pipeline of vaccine candidates is under evaluation (Fig. 6). These include irradiated sporozoites — an approach that maximizes the variety of antigens exposed149 — and subunit vaccines, which could be developed into multicomponent, multistage and multi-antigen formulations150. Although vaccines are typically designed for children, as the malaria map shrinks, both paediatric and adult populations living in newly malaria-free zones will need protection because they would probably lose any naturally acquired immunity and would, therefore, be more susceptible. Indeed, in recent years, there has been a focus on developing transmission-blocking vaccines to drive malaria elimination. This approach has been labelled altruistic, as vaccination would have no direct benefit for the person receiving it, but it would benefit the community; a regulatory pathway for such a novel approach has been proposed151,152. The most clinically advanced vaccine candidate that is based on this approach is a conjugate vaccine that targets the female gametocyte marker Pfs25 (Ref. 153), and other antigens are being tested preclinically. Monoclonal antibodies are another potential tool to provide protection. Improvements in manufacturing and high-expressing cell lines are helping to overcome the major barrier to the use of monoclonal antibodies (high costs)154, and improvements in potency and pharmacokinetics are reducing the volume and frequency of administration155. Monoclonal antibodies could be particularly useful to safely provide the relatively short-term protection needed in pregnancy. The molecular basis of the interaction between parasites and the placenta is quite well understood; two phase I trials of vaccines that are based on the VAR2CSA antigen are under way156,157.

The main data source for this Figure was Ref. 269. Not all vaccines under development are shown in the Figure. AIMV VLP, Alfalfa mosaic virus virus-like particle; AMA1, apical membrane antigen 1; AMANET, African Malaria Network Trust; ASH, Albert Schweitzer Hospital (Gabon); ChAd63, chimpanzee adenovirus 63; CHUV, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (Switzerland); CNRFP, Centre National de Recherche et de Formation sur le Paludisme (Burkina Faso); CS, circumsporozoite protein; CSP, circumsporozoite protein; EBA, erythrocyte-binding antigen; ee, elimination eradication; EP, electroporation; EPA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoprotein A; EVI, European Vaccine Initiative; CVac, chemoprophylaxis vaccine; FhCMB, Fraunhofer Center for Molecular Biotechnology (USA); GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; IP, Institut Pasteur (France); INSERM, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (France); JHU, Johns Hopkins University (USA); KCMC, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical College (Tanzania); KMRI, Kenyan Medical Research Institute; LSHTM, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (UK); M3V.Ad.PfCA, multi-antigen, multistage, adenovirus-vectored vaccine expressing Plasmodium falciparum CSP and AMA1 antigens; mAb, monoclonal antibody; ME-TRAP multiple epitope thrombospondin-related adhesion protein; MRCG, Medical Research Council (The Gambia); MSP, merozoite surface protein; MVA, modified vaccinia virus Ankara; MUK, Makerere University Kampala (Uganda); NHRC, Navrongo Health Research Centre (Ghana); NIAID, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (USA); NIMR, National Institute for Medical Research (UK); NMRC, Naval Medical Research Center (USA); PAMCPH, pregnancy-associated malaria Copenhagen; PATH, Program for Appropriate Technology in Health; PfAMA1-DiCo, diversity-covering Plasmodium falciparum AMA1; PfCelTOS, Plasmodium falciparum cell-traversal protein for ookinetes and sporozoites; PfPEBS, Plasmodium falciparum pre-erythrocytic and blood stage; PfSPZ, Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite; PfSPZ-GA1, genetically attenuated PfSPZ; pp, paediatric prevention; PRIMALVAC, PRIMVAC project (INSERM); PRIMVAC, recombinant var2CSA protein as vaccine candidate for placental malaria; Pfs25, Plasmodium falciparum 25 kDa ookinete surface antigen; PvCSP, Plasmodium vivax circumsporozoite protein; PvDBP, Plasmodium vivax Duffy-binding protein; Rh or RH, reticulocyte-binding protein homologue; SAPN, self-assembling protein nanoparticle; SSI, Statens Serum Institut (Denmark); U., University; UCAP, Université Cheikh Anta Diop (Senegal); UKT, Institute of Tropical Medicine, University of Tübingen (Germany); USAMMRC, US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command; WEHI, Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (Australia); WRAIR, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (USA). *Sponsors of late-stage clinical trials. ‡Pending review or approval by WHO prequalification, or by regulatory bodies who are members or observers of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH).

Management

No single drug is ideal against all Plasmodium spp. or all of the manifestations of the disease that occur in different patient populations. Thus, treatment must be tailored to each situation appropriately108,158. First, the treatment of uncomplicated malaria and that of severe malaria are distinct. In uncomplicated malaria, the treatment of choice is an oral medicine with high efficacy and a low adverse-effect profile. However, the preferred initial therapy in severe malaria requires rapid onset and includes the parenteral administration of an artemisinin derivative, which can rapidly clear the parasites from the blood, and it is also suitable for those patients who have changes in mental status (such as coma) that make swallowing oral medications impossible. For the treatment of malaria during pregnancy, the options are limited to the drugs that are known to be safe for both the expectant mother and the fetus, and different regimens are needed (Box 2). Different drugs are used for different Plasmodium spp., and the choice is usually driven more by drug resistance frequencies (which are lower in P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae and P. knowlesi than in P. falciparum) than by species differences as such. Thus, chloroquine, with its low cost and excellent safety, is used in most cases of non-P. falciparum malaria, where it remains effective, whereas P. falciparum malaria requires newer medicines that overcome resistance issues. The persistence of P. vivax and P. ovale hypnozoites, even after clearance of the stages that cause symptoms, necessitates additional treatments. Only primaquine targets hypnozoites.

P. falciparum malaria

The mainstay treatments for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria are ACTs: fixed-dose combinations of two drugs, an artemisinin derivative and a quinine derivative108 (Box 4; Table 1).

Owing to its high lipophilicity, artemisinin itself is not the molecule of choice in any stringent regulatory authority-approved combination. Instead, semisynthetic derivatives are used: namely, DHA (the reduced hemiacetal of the major active metabolite of many artemisinin derivatives), artesunate (a succinate prodrug of DHA that is highly water-soluble) or artemether (a methylether prodrug of DHA).

Quinine has been used in medicine for centuries159, but it was only in the mid-20th century that a synthetic form was made and the emerging pharmaceutical and government research sectors delivered the next-generation medicines that built on it. The combination partners of choice are 4-aminoquinolines (for example, amodiaquine, piperaquine and pyronaridine) and amino-alcohols (such as mefloquine or lumefantrine); these molecules are believed to interfere with haemozoin formation. There are now five ACTs that have been approved or are close to approval by the FDA, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) or WHO prequalification (Figs 7,8; Table 1). In pivotal clinical studies, these combinations have proven extremely effective (achieving an adequate clinical and parasitological response (that is, the absence of parasitaemia at day 28 in >94% of patients; for example, see Ref. 160), are well-tolerated (as they have been given to >300 million paediatric patients), are affordable (typically under US$1 per dose) and, thanks to ingenious formulations and packaging, are stable in tropical climate conditions.

a | Preclinical candidates. b | Compounds or compound combinations that are in clinical development. The multitude of molecules that target only the asexual blood stages reflects the fact that many of these compounds are at an early stage of development, and further assessment of their Target Candidate Profile is still ongoing. KAF156 and KAE609 were discovered in a multiparty collaboration between the Novartis Institute for Tropical Disease (Singapore), the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation (GNF; USA), the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, the Biomedical Primate Research Centre (The Netherlands), the Wellcome Trust (UK) and Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV). DSM265 was discovered through a collaboration involving the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW; USA), the University of Washington (UW; USA), Monash University (Australia), GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and MMV. MMV(390)048 was discovered through a collaboration involving the University of Cape Town (UCT; South Africa), the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, Monash University, Syngene and MMV. SJ(557)733 was discovered in a collaboration involving St Jude Children's Research Hospital (USA), Rutgers University (USA), Monash University and MMV. Note that not all compounds are shown in this Figure, and updates can be found on the MMV website (www.mmv.org). CDRI, Central Drug Research Institute (India); ITM, Institute of Tropical Medicine; MRC, Medical Research Council; HKUST, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology; U., University. *Part of a combination that aims to be a new single-exposure radical cure (Target Product Profile 1). ‡Product that targets the prevention of relapse in Plasmodium vivax malaria. §3-day cure, artemisinin-based combination therapy. ||Severe malaria and pre-referral treatment.

See the Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) website (www.mmv.org) for updates. CDRI, Central Drug Research Institute (India); GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; ITM, Institute of Tropical Medicine; U., University; UCT, University of Cape Town (South Africa); UTSW, University of Texas Southwestern (USA); UW, University of Washington (USA). *Part of a combination that aims to be a new single-exposure radical cure (Target Product Profile 1). ‡Product that targets the prevention of relapse in Plasmodium vivax malaria. §3-day cure, artemisinin-based combination therapy.

Following the results of comprehensive studies in Africa and Asia, the injectable treatment of choice for severe P. falciparum malaria is artesunate161–163. In the United States, artesunate for intravenous use is available as an Investigational New Drug (IND) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) malaria hotline and shows efficacies of >90% even in patients who are already unconscious161. Sometimes, however, in low-income countries, it is necessary to administer intravenous quinine or quinine while awaiting an artesunate supply. Suppositories of artesunate are in late-stage product development164 and are already available in Africa as a pre-referral treatment to keep patients alive while they reach a health clinic.

P. vivax malaria

Chloroquine or ACTs are WHO-recommended for uncomplicated P. vivax malaria108 (although chloroquine is no longer used in several countries, such as Indonesia). As chloroquine-resistant P. vivax is becoming increasingly widespread, particularly in Asia, the use of ACTs is increasing; although only artesunate–pyronaridine is approved for the treatment of blood-stage P. vivax malaria, the other ACTs are also effective and are used off-label. Relapses of P. vivax malaria present a problem in malaria control. Relapse frequencies differ among P. vivax strains; they are high (typically within 3 weeks) in all-year transmission areas, such as Papua New Guinea, but relapse occurs on average after 7 months in areas with a dry or winter season. Some P. vivax strains, such as the Moscow and North Korea strains, are not, in most cases, symptomatic at the time of first infection but become symptomatic only following reactivation of the hypnozoites165. Primaquine needs to be administered in addition to the primary treatment to prevent relapse and transmission, which can occur even years after the primary infection. Primaquine treatment, however, requires 14 days of treatment, has gastrointestinal adverse effects in some patients, and is contraindicated in pregnant women and in patients who are deficient in or express low levels of G6PD (as it can cause haemolysis). Tafenoquine166, a next-generation 8-aminoquinoline, is currently completing phase III clinical studies. As with patients receiving primaquine, patients receiving tafenoquine will still require an assessment of their G6PD enzyme activity to ensure safe use of the drug and to determine the optimal dose. In phase II studies, tafenoquine was shown to have an efficacy similar to that of primaquine but with a single dose only compared with the 7–14-day treatment with primaquine; higher patient compliance is expected to be a major benefit of a single-dose regimen. The ultimate elimination of P. vivax malaria will be dependent on the availability of safe and effective anti-relapse agents, and is, therefore, a major focus of the drug discovery community.

Drug resistance

The two drugs in ACTs have very different pharmacokinetic profiles in patients. The artemisinin components have a plasma half-life of only a few hours yet can reduce parasitaemia by three-to-four orders of magnitude. By contrast, the 4-aminoquinolines and amino-alcohols have long terminal half-lives (>4 days), providing cure (defined as an adequate clinical and parasitological response) and varying levels of post-treatment prophylaxis. The prolonged half-life of the non-artemisinin component of ACTs has raised concerns in the research community owing to the risk of drug resistance development. However, the effectiveness of the ACTs in rapidly reducing parasitaemia suggests that any emerging resistance has arisen largely as a result of poor clinical practice, including the use of artemisinin derivatives as monotherapy, a lack of patient compliance and substandard medicine quality (including counterfeits); these are all situations in which large numbers of parasites are exposed to a single active molecule167. However, resistance to piperaquine168 and partial resistance to artemisinin169 (which manifests as a reduced rate of parasite clearance rate rather than a shift in the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50)) has been confirmed in the Greater Mekong subregion, as well as resistance to mefloquine and amodiaquine in various parts of the world170. Africa has so far been spared, but reports of treatment failure for either artemisinin171 or ACT172 in African isolates of P. falciparum have raised concerns. Thus, artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium spp. and insecticide-resistant mosquitoes are major threats to the progress that has been made in reducing the number of malaria-related deaths through current control programmes. It is important to emphasize that progress against malaria has historically been volatile; in many areas, the disease has re-emerged as the efficacy of old drugs has been lost in strains that developed resistance.

Many advances have been made in identifying genetic markers in Plasmodium spp. that correlate with resistance to clinically used drugs (Table 2). These markers enable the research and medical communities to proactively survey parasite populations to make informed treatment choices. Cross-resistance profiles reveal reciprocity between 4-aminoquinolines and amino-alcohols (that is, parasites resistant to one class are also less sensitive to the other). In addition, a drug can exert two opposite selective pressures: one towards the selection of resistant mutants and the other towards the selection of strains that have increased sensitivity to a different drug, a phenomenon known as ‘inverse selective pressure’ (Refs 173,174). These findings support the introduction of treatment rotation or triple combination therapies as potential future options. Finally, the drug discovery and development pipeline is delivering not only new compounds that have novel modes of action and overcome known resistant strains but also chemicals that have the potential to be effective in a single dose, which could overcome compliance issues. Nevertheless, policymakers need to be on high alert to prevent or rapidly eliminate outbreaks of resistant strains, and to prioritize the development of new treatments.

The drug discovery and development pipeline

The most comprehensive antimalarial discovery portfolio has been developed by the not-for-profit product development partnership Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) in collaboration with its partners in both academia and the pharmaceutical industry, with support from donors (mainly government agencies and philanthropic foundations) (Fig. 7). Promising compound series have been identified from three approaches: hypothesis-driven design to develop alternatives to marketed compounds (for example, synthetic peroxides such as ozonides); target-based screening and rational design (for example, screening of inhibitors of P. falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (PfDHODH)); and phenotypic screening175. Phenotypic screening has been the most successful approach to date, in terms of delivering preclinical candidates and identifying — through the sequencing of resistant mutants — novel molecular targets. However, with advances in the understanding of parasite biology and in molecular biology technology, target-based approaches will probably have a substantial role in coming years.

Two combinations — OZ439 (also known as artefenomel) with ferroquine (Sanofi and MMV) and KAF156 with lumefantrine (Novartis and MMV) — are about to begin phase IIb development to test the efficacy of single-dose cure and, in the case of KAF156–lumefantrine, also 2-day or 3-day cures. OZ439 is a fully synthetic peroxide for which sustained plasma exposure is achieved by a single oral dose in humans176,177; the hope is that it could replace the three independent doses required for artemisinin derivatives. Ferroquine is a next-generation 4-aminoquinoline without cross-resistance to chloroquine, amodiaquine or piperaquine178,179. KAF156 is a novel imidazolopiperazine that has an unknown mechanism of action180–182, but its resistance marker — P. falciparum cyclic amine resistance locus (pfcarl) — seems to encode a transporter on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane of the parasite. Interestingly, whereas OZ439 and ferroquine principally affect the asexual blood stages, KAF156 also targets both the asexual liver stage and the sexual gametocyte stage and, therefore, could have an effect on transmission.

Two other compounds, KAE609 (also known as cipargamin183,184) and DSM265 (Refs 185–188), are poised to begin phase IIb and are awaiting decisions on combination partners. KAE609 is a highly potent spiroindolone that provides parasite clearance in patients even more rapidly than peroxides; its assumed mode of action is the inhibition of PfATP4 (Fig. 3), which is encoded by its resistance marker and is a transporter on the parasite plasma membrane that regulates Na+ and H+ homeostasis. Inhibition of this channel, which was identified through the sequencing of resistant mutants, increases Na+ concentrations and pH, resulting in parasite swelling, rigidity and fragility, thereby contributing to host parasite clearance in the spleen in addition to intrinsic parasite killing. In addition, effects on cholesterol levels in the parasite plasma membrane have been noted that are also likely to contribute to parasite killing by leading to an increased rigidity that results in more rapid clearance in vivo189. DSM265 is a novel triazolopyrimidine that has both blood-stage and liver-stage activity, and that selectively inhibits PfDHODH (Fig. 3). It was optimized for drug-like qualities from a compound that was identified from a high-throughput screen of a small-molecule library186,190. DSM265 maintains a serum concentration that is above its minimum parasiticidal concentration in humans for 8 days, and has shown efficacy in both treatment and chemoprotection models in human volunteers in phase Ib trials185,188.

Within phase I, new compounds are first assessed for safety and pharmacokinetics, and then for efficacy against the asexual blood or liver stages of Plasmodium spp. using a controlled human malaria infection model in healthy volunteers144. This model provides a rapid and cost-effective early proof of principle and, by modelling the concentration–response correlation, increases the accuracy of dose predictions for further clinical studies. The 2-aminopyridine MMV(390)048 (also known as MMV048 (Refs 191,192)), SJ(557)733 (also known as (+)-SJ733 (Refs 57,193)) and P218 (Ref. 194) are currently progressing through phase I. MMV(390)048 inhibits PfPI(4)K (Fig. 3), and this inhibition affects the asexual liver and blood stages, as well as the sexual gametocyte stage. MMV(390)048 has good exposure in animal models192, suggesting that it could potentially be used in a single dose in combination with another drug. SJ(557)733, which is a dihydroisoquinoline, inhibits PfATP4 and is an alternative partner that has a completely different structure from that of KAE609, and it has excellent preclinical safety and development potential. P218 is currently being evaluated for testing in controlled human malaria infection cohorts.

A further eight compounds are undergoing active preclinical development195. Of these compounds, four are alternatives to the leading compounds that target established mechanisms: the aminopyrazole PA92 (also known as PA-21A092 (Ref. 196)) and the thiotriazole GSK030 (also known as GSK3212030A) both target PfATP4; DSM421 (Ref. 197) is a triazolopyrimidine alternative to DSM265; and UCT943 (also known as MMV642943)198 is an alternative to MMV(390)048. Three compounds show novel mechanisms of action or resistance markers: M5717 (also known as DDD498 or DDD107498 (Ref. 199)) inhibits P. falciparum elongation factor 2 (and, therefore, protein synthesis) and has outstanding efficacy against all parasite life-cycle stages; MMV253 (also known as AZ13721412)200 is a fast-acting triaminopyrimidine with a V-type ATPase as resistance marker; and AN13762 (also known as AN762) is a novel oxaborole201 with a novel resistance marker. All of these compounds have been developed through collaborations with MMV.

The eighth compound in active preclinical development, led by Jacobus Pharmaceuticals, is JPC3210 (Ref. 202), which is a novel aminocresol that improves upon the historical candidate (WR194965) that was developed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and tested in patients at the time of the development of mefloquine in the 1970s. JPC3210 has an unknown mechanism of action and has potent, long-lasting efficacy in preclinical models, suggesting its potential to be used in a single dose for both treatment and prophylaxis202.

Quality of life

Malaria is one among the diseases of poverty. The WHO website states the following: “There is general agreement that poverty not only increases the risk of ill health and vulnerability of people, it also has serious implications for the delivery of effective health-care such as reduced demand for services, lack of continuity or compliance in medical treatment, and increased transmission of infectious diseases” (Ref. 203). The socioeconomic burden of malaria is enormous, and although the disease predominantly affects children, it is a serious obstacle to a country's development and economy204. Malaria is responsible for annual expenses of billions of euros in some African countries205. In many endemic areas, each individual suffers multiple episodes of malaria per year, with each episode causing a loss of school time for children and work time for their parents and guardians. Despite the declining trends in malaria morbidity and mortality, the figures are still disconcertingly high for a disease that is entirely preventable and treatable16.