This archival content was originally written for and published on KPCC.org. Keep in mind that links and images may no longer work — and references may be outdated.

Fukushima radiation helps researchers study ocean currents

It's been four years since an earthquake and tsunami combo caused a nuclear meltdown in Japan, resulting in a significant amount of radioactive material leaking into the Pacific Ocean.

Since then, the isotopes from the Fukushima plant have slowly travelled toward North America.

Scientists say none of the tainted water has washed up on West Coast shores yet, and when it does, they expect concentrations of nuclear material to be well below dangerous levels.

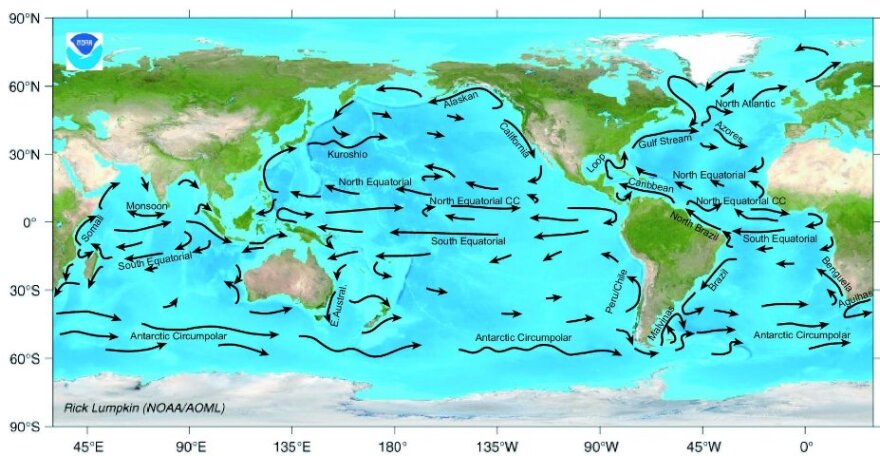

Still, as this material moves through the ocean, scientists have been tracking it to learn more about how ocean currents work.

Radioactive elements such as the cesium and iodine associated with Fukushima make for excellent tracers, said Ken Buesseler with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

That's because these materials first entered the ocean on a specific date and so their progress can be monitored from then on.

from

on Vimeo.

So far, these elements have shown that water from Asia travels more slowly to North America than many computer models predicted.

Buesseler also noted that the leading models had significantly different predictions for when the tainted material should reach North America.

This new data will help researchers tweak the models to better understand how material moves through the Pacific.

"We simply would want to know better... when a contaminant might show up from any source in the ocean," Buesseler said.

These isotopes could also help researchers better understand a phenomenon called upwelling. This occurs when surface water off shore mixes with deeper ocean water.

By tracing the isotopes as they go through this process researchers will be able to see how upwelling affects when distant water reaches the shore.

"There are some big questions we can address by looking at these relatively small amounts of Fukushima isotopes on our coastline," he said.

Studying isotopes in the ocean is not a new technique. Scientists used material released after nuclear weapons tests in the '50s and '60s to do early work on ocean currents.

Buesseler himself studied material released during the Chernobyl disaster of the 1980s to learn more about the water patters of the Black Sea.

Later this year he plans to travel from Hawaii to Alaska in a research vessel to sample water in hopes of learning more.