Abstract

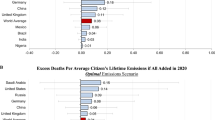

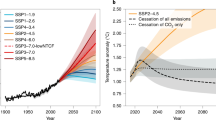

Societal risks increase as Earth warms, and increase further for emissions trajectories accepting relatively high levels of near-term emissions while assuming future negative emissions will compensate, even if they lead to identical warming as trajectories with reduced near-term emissions1. Accelerating carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions reductions, including as a substitute for negative emissions, hence reduces long-term risks but requires dramatic near-term societal transformations2. A major barrier to emissions reductions is the difficulty of reconciling immediate, localized costs with global, long-term benefits3,4. However, 2 °C trajectories not relying on negative emissions or 1.5 °C trajectories require elimination of most fossil-fuel-related emissions. This generally reduces co-emissions that cause ambient air pollution, resulting in near-term, localized health benefits. We therefore examine the human health benefits of increasing 21st-century CO2 reductions by 180 GtC, an amount that would shift a ‘standard’ 2 °C scenario to 1.5 °C or could achieve 2 °C without negative emissions. The decreased air pollution leads to 153 ± 43 million fewer premature deaths worldwide, with ~40% occurring during the next 40 years, and minimal climate disbenefits. More than a million premature deaths would be prevented in many metropolitan areas in Asia and Africa, and >200,000 in individual urban areas on every inhabited continent except Australia.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson, K. & Peters, G. The trouble with negative emissions. Science 354, 182–183 (2016).

Clarke, L. et al. in Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change (eds Edenhofer, O. et al.) 413–510 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Berns, G. S., Laibson, D. & Loewenstein, G. Intertemporal choice—toward an integrative framework. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 482–488 (2007).

Leiserowitz, A. A. American risk perceptions: is climate change dangerous? Risk Anal. 25, 1433–1442 (2005).

Collins, M. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) Ch. 12 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Rogelj, J. et al. Differences between carbon budget estimates unravelled. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 245–252 (2016).

Delucchi, M. A. & Jacobson, M. Z. Providing all global energy with wind, water, and solar power. Part II: Reliability, system and transmission costs, and policies. Energy Policy 39, 1170–1190 (2011).

Jacobson, M. Z. & Delucchi, M. A. Providing all global energy with wind, water, and solar power. Part I: Technologies, energy resources, quantities and areas of infrastructure, and materials. Energy Policy 39, 1154–1169 (2011).

Smith, P. et al. Biophysical and economic limits to negative CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 42–50 (2016).

Buck, H. J. Rapid scale-up of negative emissions technologies: social barriers and social implications. Climatic Change 139, 155–167 (2016).

Shindell, D. T. The social cost of atmospheric release. Climatic Change 130, 313–326 (2015).

Forouzanfar, M. H. et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 388, 1659–1724 (2016).

Jakob, M & Steckel, J. C. Implications of climate change mitigation for sustainable development. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 104010 (2016).

von Stechow, C.et al. 2 °C and SDGs: united they stand, divided they fall? Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 034022 (2016).

Campbell-Lendrum, D. & Woodruff, R. in Climate Change: Quantifying the Health Impact at National and Local Levels (eds Prüss-Üstün, A. & Corvalan, C.) 1–66 (World Health Organization, 2007).

Haines, A. et al. Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: overview and implications for policy makers. Lancet 374, 2104–2114 (2009).

Silva, R. A. et al. The effect of future ambient air pollution on human premature mortality to 2100 using output from the ACCMIP model ensemble. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 9847–9862 (2016).

Anenberg, S. C. et al. Global air quality and health co-benefits of mitigating near-term climate change through methane and black carbon emission controls. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 831–839 (2012).

Rogelj, J. et al. Energy system transformations for limiting end-of-century warming to below 1.5 °C. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 519–527 (2015).

The Economic Consequences of Outdoor Air Pollution (OECD, 2016); https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264257474-en.

Schleussner, C. F. et al. Differential climate impacts for policy-relevant limits to global warming: the case of 1.5 °C and 2 °C. Earth Syst. Dynam. 7, 327–351 (2016).

IPCC: Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability (eds Field, C. B. et al.) 1–32 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

van Vuuren, D. P. et al. RCP2.6: exploring the possibility to keep global mean temperature increase below 2 °C. Climatic Change 109, 95–116 (2011).

Schmidt, G. A. et al. Configuration and assessment of the GISS ModelE2 contributions to the CMIP5 archive. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 6, 141–184 (2014).

Shindell, D. T. et al. Interactive ozone and methane chemistry in GISS-E2 historical and future climate simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2653–2689 (2013).

Shindell, D. T. et al. Radiative forcing in the ACCMIP historical and future climate simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2939–2974 (2013).

Prather, M. J. Numerical advection by conservation of second-order moments. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 6671–6681 (1986).

Burnett, R. T. et al. An integrated risk function for estimating the global burden of disease attributable to ambient fine particulate matter exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 397–403 (2014).

Turner, M. C. et al. Long-term ozone exposure and mortality in a large prospective study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 193, 1134–1142 (2016).

Air Pollution: A Global Assessment of Exposure and Burden of Disease (WHO, 2016).

United Nations World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision (UN, 2011).

Apte, J. S. et al. Addressing global mortality from ambient PM2.5. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 8057–8066 (2015).

Cohen, A. J. et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 389, 1907–1918 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank G. Russell for help with implementing the constituent moment method, NASA GISS for support and the NASA High-End Computing Program through the NASA Center for Climate Simulation at GSFC for computational resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.S. conceived the project. G.F. performed the simulations and health impact calculations. K.S. assembled ozone data sets for use in model evaluation and helped develop ozone impact analyses. C.S. mapped the health outcomes onto metropolitan areas. D.S. wrote the paper, with all authors providing input.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussion 1–6, Supplementary Figures 1–6, Supplementary Tables 1–2 and Supplementary References

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shindell, D., Faluvegi, G., Seltzer, K. et al. Quantified, localized health benefits of accelerated carbon dioxide emissions reductions. Nature Clim Change 8, 291–295 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0108-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0108-y

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced atmospheric oxidation toward carbon neutrality reduces methane’s climate forcing

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Critical environmental management accounting practices influencing service delivery of growing cities in a developing economy: a review and conceptual framework

Environment Systems and Decisions (2024)

-

Modeling pressure drop values across ultra-thin nanofiber filters with various ranges of filtration parameters under an aerodynamic slip effect

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Global fossil fuel reduction pathways under different climate mitigation strategies and ambitions

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Effects of global climate mitigation on regional air quality and health

Nature Sustainability (2023)