Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a debilitating disease that is characterized by depressed mood, diminished interests, impaired cognitive function and vegetative symptoms, such as disturbed sleep or appetite. MDD occurs about twice as often in women than it does in men and affects one in six adults in their lifetime. The aetiology of MDD is multifactorial and its heritability is estimated to be approximately 35%. In addition, environmental factors, such as sexual, physical or emotional abuse during childhood, are strongly associated with the risk of developing MDD. No established mechanism can explain all aspects of the disease. However, MDD is associated with alterations in regional brain volumes, particularly the hippocampus, and with functional changes in brain circuits, such as the cognitive control network and the affective–salience network. Furthermore, disturbances in the main neurobiological stress-responsive systems, including the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the immune system, occur in MDD. Management primarily comprises psychotherapy and pharmacological treatment. For treatment-resistant patients who have not responded to several augmentation or combination treatment attempts, electroconvulsive therapy is the treatment with the best empirical evidence. In this Primer, we provide an overview of the current evidence of MDD, including its epidemiology, aetiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

$99.00 per year

only $99.00 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Seedat, S. et al. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 785–795 (2009).

Bromet, E. et al. Cross-national epidemiology of DSM-IV major depressive episode. BMC Med. 9, 90 (2011).

Vos, T. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386, 743–800 (2015).

Whooley, M. A. & Wong, J. M. Depression and cardiovascular disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 9, 327–354 (2013).

World Health Organization. Suicide. WHOhttp://www.who.int/topics/suicide/en/ (2016).

Chesney, E., Goodwin, G. M. & Fazel, S. Risks of all cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta-review. World Psychiatry 13, 153–160 (2014).

Flint, J. & Kendler, K. S. The genetics of major depression. Neuron 81, 484–503 (2014). This comprehensive review describes the state-of-the-art insights into the genetics of MDD, why it is not easy to find consistent genetic variants of MDD and what should be done to unravel the genetics of MDD.

Li, M., D'Arcy, C. & Meng, X. Maltreatment in childhood substantially increases the risk of adult depression and anxiety in prospective cohort studies: systematic review, meta-analysis, and proportional attributable fractions. Psychol. Med. 46, 717–730 (2016).

Etkin, A., Bü chel, C. & Gross, J. J. The neural bases of emotion regulation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 693–700 (2015).

Kupfer, D. J., Frank, E. & Phillips, M. L. Major depressive disorder: new clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet 379, 1045–1055 (2012).

Rush, A. J. et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am. J. Psychiatry 163, 1905–1917 (2006).

Thase, M. E. et al. Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second-step treatments: a STAR*D report. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 739–752 (2007).

Patten, S. B. Accumulation of major depressive episodes over time in a prospective study indicates that retrospectively assessed lifetime prevalence estimates are too low. BMC Psychiatry 9, 19 (2009).

Moffitt, T. E. et al. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol. Med. 40, 899–909 (2010).

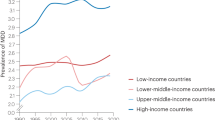

Kessler, R. C. & Bromet, E. J. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu. Rev. Public Health 34, 119–138 (2013). This paper describes the general worldwide prevalence of MDD and the main contributing risk factors to the occurrence of depression.

Kendler, K. S. et al. The similarity of the structure of DSM-IV criteria for major depression in depressed women from China, the United States and Europe. Psychol. Med. 45, 1945–1954 (2015).

Wang, P. S. et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet 370, 841–850 (2007).

Ten Have, M., Nuyen, J., Beekman, A. & de Graaf, R. Common mental disorder severity and its association with treatment contact and treatment intensity for mental health problems. Psychol. Med. 43, 2203–2213 (2013).

Eaton, W. W. et al. Natural history of Diagnostic Interview Schedule/DSM-IV major depression. The Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area follow-up. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 54, 993–999 (1997).

Penninx, B. W. J. H. et al. Two-year course of depressive and anxiety disorders: results from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J. Affect. Disord. 133, 76–85 (2011).

Risch, N. et al. Interaction between the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR), stressful life events, and risk of depression: a meta-analysis. JAMA 301, 2462–2471 (2009).

Lorant, V. et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 157, 98–112 (2003).

Peyrot, W. J. et al. The association between lower educational attainment and depression owing to shared genetic effects? Results in ∼25,000 subjects. Mol. Psychiatry 20, 735–743 (2015).

Heim, C. & Binder, E. B. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene-environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp. Neurol. 233, 102–111 (2012). This excellent review summarizes the neurobiological and clinical sequelae of early-life stress.

Hovens, J. G. F. M. et al. Impact of childhood life events and trauma on the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 126, 198–207 (2012).

Spijker, J. et al. Duration of major depressive episodes in the general population: results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Br. J. Psychiatry 181, 208–213 (2002).

Keller, M. B. et al. Time to recovery, chronicity, and levels of psychopathology in major depression. A 5-year prospective follow-up of 431 subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 49, 809–816 (1992).

Ustün, T. B. & Kessler, R. C. Global burden of depressive disorders: the issue of duration. Br. J. Psychiatry 181, 181–183 (2002).

Boschloo, L. et al. The four-year course of major depressive disorder: the role of staging and risk factor determination. Psychother. Psychosom. 83, 279–288 (2014).

Wells, K. B., Burnam, M. A., Rogers, W., Hays, R. & Camp, P. The course of depression in adult outpatients. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 49, 788–794 (1992).

Ormel, J., Oldehinkel, A. J., Nolen, W. A. & Vollebergh, W. Psychosocial disability before, during, and after a major depressive episode: a 3-wave population-based study of state, scar, and trait effects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61, 387–392 (2004).

Vos, T. et al. The burden of major depression avoidable by longer-term treatment strategies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61, 1097–1103 (2004).

Penninx, B. W. J. H., Milaneschi, Y., Lamers, F. & Vogelzangs, N. Understanding the somatic consequences of depression: biological mechanisms and the role of depression symptom profile. BMC Med. 11, 129 (2013). This article summarizes the somatic health consequences of MDD and its underlying mechanisms.

Cuijpers, P. et al. Comprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific illnesses. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 453–462 (2014).

Walker, E. R., McGee, R. E. & Druss, B. G. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 334–341 (2015).

Geschwind, D. H. & Flint, J. Genetics and genomics of psychiatric disease. Science 349, 1489–1494 (2015).

Lee, S. H. et al. Genetic relationship between five psychiatric disorders estimated from genome-wide SNPs. Nat. Genet. 45, 984–994 (2013).

Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet 381, 1371–1379 (2013).

Bosker, F. J. et al. Poor replication of candidate genes for major depressive disorder using genome-wide association data. Mol. Psychiatry 16, 516–532 (2011).

Ripke, S. et al. A mega-analysis of genome-wide association studies for major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 18, 497–511 (2013).

Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511, 421–427 (2014).

Hyman, S. Mental health: depression needs large human-genetics studies. Nature 515, 189–191 (2014).

CONVERGE Consortium. Sparse whole-genome sequencing identifies two loci for major depressive disorder. Nature 523, 588–591 (2015).

Hyde, C. L. et al. Identification of 15 genetic loci associated with risk of major depression in individuals of European descent. Nat. Genet. 48, 1031–1036 (2016).

Smith, D. J. et al. Genome-wide analysis of over 106 000 individuals identifies 9 neuroticism-associated loci. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 749–757 (2016).

Okbay, A. et al. Genetic variants associated with subjective well-being, depressive symptoms, and neuroticism identified through genome-wide analyses. Nat. Genet. 48, 624–633 (2016).

Kessler, R. C. The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 48, 191–214 (1997).

Meaney, M. J. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1161–1192 (2001).

Stetler, C. & Miller, G. E. Depression and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal activation: a quantitative summary of four decades of research. Psychosomat. Med. 73, 114–126 (2011).

Entringer, S., Buss, C. & Wadhwa, P. D. Prenatal stress, development, health and disease risk: a psychobiological perspective — 2015 Curt Richter Award Paper. Psychoneuroendocrinology 62, 366–375 (2015).

Stein, A. et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 384, 1800–1819 (2014).

Klengel, T. & Binder, E. B. Epigenetics of stress-related psychiatric disorders and gene x environment interactions. Neuron 86, 1343–1357 (2015).

Klengel, T. et al. Allele-specific FKBP5 DNA demethylation mediates gene–childhood trauma interactions. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 33–41 (2013).

Anacker, C., Zunszain, P. A., Carvalho, L. A. & Pariante, C. M. The glucocorticoid receptor: pivot of depression and of antidepressant treatment? Psychoneuroendocrinology 36, 415–425 (2011).

McGowan, P. O. et al. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 342–348 (2009).

Holsboer, F. & Ising, M. Stress hormone regulation: biological role and translation into therapy. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 61, 81–109 (2010). This comprehensive review provides an in-depth discussion of the HPA axis and its role in psychopathology.

Schatzberg, A. F. Anna-Monika Award Lecture, DGPPN Kongress, 2013: the role of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis in the pathogenesis of psychotic major depression. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 16, 2–11 (2015).

Knorr, U., Vinberg, M., Kessing, L. V. & Wetterslev, J. Salivary cortisol in depressed patients versus control persons: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35, 1275–1286 (2010).

Hinkelmann, K. et al. Cognitive impairment in major depression: association with salivary cortisol. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 879–885 (2009).

Nelson, J. C. & Davis, J. M. DST studies in psychotic depression: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Psychiatry 154, 1497–1503 (1997).

Murri, M. B. et al. HPA axis and aging in depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 41, 46–62 (2014).

Goodyer, I. M., Herbert, J., Tamplin, A. & Altham, P. M. Recent life events, cortisol, dehydroepiandrosterone and the onset of major depression in high-risk adolescents. Br. J. Psychiatry 177, 499–504 (2000).

Harris, T. O. et al. Morning cortisol as a risk factor for subsequent major depressive disorder in adult women. Br. J. Psychiatry 177, 505–510 (2000).

Fardet, L., Petersen, I. & Nazareth, I. Suicidal behavior and severe neuropsychiatric disorders following glucocorticoid therapy in primary care. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 491–497 (2012).

McKay, M. S. & Zakzanis, K. K. The impact of treatment on HPA axis activity in unipolar major depression. J. Psychiatr. Res. 44, 183–192 (2010).

Nemeroff, C. B. et al. Elevated concentrations of CSF corticotropin-releasing factor-like immunoreactivity in depressed patients. Science 226, 1342–1344 (1984). This seminal paper was the first to demonstrate increased concentrations of CRH in the CSF in patients with MDD.

Aubry, J. M. CRF system and mood disorders. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 54, 20–24 (2013).

Jahn, H. et al. Metyrapone as additive treatment in major depression: a double-blind and placebo-controlled trial. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 61, 1235–1244 (2004).

McAllister-Williams, R. H. et al. Antidepressant augmentation with metyrapone for treatment-resistant depression (the ADD study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 117–127 (2016).

Otte, C. et al. Modulation of the mineralocorticoid receptor as add-on treatment in depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled proof-of-concept study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 44, 339–346 (2010).

Otte, C. et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor stimulation improves cognitive function and decreases cortisol secretion in depressed patients and healthy individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 40, 386–393 (2015).

Hodes, G. E., Kana, V., Menard, C., Merad, M. & Russo, S. J. Neuroimmune mechanisms of depression. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1386–1393 (2015).

Benros, M. E. et al. Autoimmune diseases and severe infections as risk factors for mood disorders: a nationwide study. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 812–820 (2013).

Myint, A. M., Schwarz, M. J., Steinbusch, H. W. & Leonard, B. E. Neuropsychiatric disorders related to interferon and interleukins treatment. Metab. Brain Dis. 24, 55–68 (2009).

Dowlati, Y. et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 67, 446–457 (2010). This meta-analysis of 24 case–control studies showed increased concentrations of circulating cytokines (TNF and IL-6) in MDD.

Haapakoski, R., Mathieu, J., Ebmeier, K. P., Alenius, H. & Kivimaki, M. Cumulative meta-analysis of interleukins 6 and 1β, tumour necrosis factor α and C-reactive protein in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 49, 206–215 (2015).

Jansen, R. et al. Gene expression in major depressive disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 339–347 (2016).

Khandaker, G. M., Pearson, R. M., Zammit, S., Lewis, G. & Jones, P. B. Association of serum interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein in childhood with depression and psychosis in young adult life: a population-based longitudinal study. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 1121–1128 (2014).

Setiawan, E. et al. Role of translocator protein density, a marker of neuroinflammation, in the brain during major depressive episodes. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 268–275 (2015). This small cross-sectional case–control study using PET provided in vivo evidence for neuroinflammation in the brains of patients with MDD.

Steiner, J. et al. Immunological aspects in the neurobiology of suicide: elevated microglial density in schizophrenia and depression is associated with suicide. J. Psychiatr. Res. 42, 151–157 (2008).

Köhler, O. et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 1381–1391 (2014).

Molendijk, M. L. et al. Serum BDNF concentrations as peripheral manifestations of depression: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analyses on 179 associations (n = 9484). Mol. Psychiatry 19, 791–800 (2014).

Egeland, M., Zunszain, P. A. & Pariante, C. M. Molecular mechanisms in the regulation of adult neurogenesis during stress. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 189–200 (2015).

Schildkraut, J. J. The catecholamine hypothesis of affective disorders: a review of supporting evidence. Am. J. Psychiatry 122, 509–522 (1965).

Belmaker, R. H. Bipolar disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 476–486 (2004).

Wong, M. L. & Licinio, J. Research and treatment approaches to depression. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 343–351 (2001).

Kempton, M. J. et al. Structural neuroimaging studies in major depressive disorder. Meta-analysis and comparison with bipolar disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 68, 675–690 (2011).

Schmaal, L. et al. Subcortical brain alterations in major depressive disorder: findings from the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol. Psychiatry 21, 806–812 (2015). This meta-analysis of structural MRI compared brain imaging data from 1,728 patients with MDD and 7,199 controls in a large international consortium. Results indicate subtle subcortical volume changes in MDD, with the most robust finding being smaller hippocampal volumes in patients with MDD than in controls.

Schmaal, L. et al. Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Mol. Psychiatry http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.60 (2016).

Goodkind, M. et al. Identification of a common neurobiological substrate for mental illness. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 305–315 (2015).

Cole, J., Costafreda, S. G., McGuffin, P. & Fu, C. H. Hippocampal atrophy in first episode depression: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. J. Affect. Disord. 134, 483–487 (2011).

Maier, S. U., Makwana, A. B. & Hare, T. A. Acute stress impairs self-control in goal-directed choice by altering multiple functional connections within the brain's decision circuits. Neuron 87, 621–631 (2015).

Nusslock, R. & Miller, G. E. Early-life adversity and physical and emotional health across the lifespan: a neuroimmune network hypothesis. Biol. Psychiatry 80, 23–32 (2016).

Hamilton, J. P. et al. Functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and new integration of base line activation and neural response data. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 693–703 (2012).

Pizzagalli, D. A. Depression, stress, and anhedonia: toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 10, 393–423 (2014).

Satterthwaite, T. D. et al. Common and dissociable dysfunction of the reward system in bipolar and unipolar depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 2258–2268 (2015).

Sheline, Y. I. et al. The default mode network and self-referential processes in depression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 1942–1947 (2009).

Dutta, A., McKie, S. & Deakin, J. F. Resting state networks in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 224, 139–151 (2014).

Cooney, R. E., Joormann, J., Eugene, F., Dennis, E. L. & Gotlib, I. H. Neural correlates of rumination in depression. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 10, 470–478 (2010).

Hamilton, J. P. et al. Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biol. Psychiatry 70, 327–333 (2011).

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Ford, J. M. Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 8, 49–76 (2012).

Cole, M. W. et al. Multi-task connectivity reveals flexible hubs for adaptive task control. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1348–1355 (2013).

Kaiser, R. H., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Wager, T. D. & Pizzagalli, D. A. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 603–611 (2015).

Pizzagalli, D. A. et al. Reduced caudate and nucleus accumbens response to rewards in unmedicated individuals with major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 166, 702–710 (2009).

Hamilton, J. P., Chen, M. C. & Gotlib, I. H. Neural systems approaches to understanding major depressive disorder: an intrinsic functional organization perspective. Neurobiol. Dis. 52, 4–11 (2013).

Keller, J., Schatzberg, A. F. & Maj, M. Current issues in the classification of psychotic major depression. Schizophrenia Bull. 33, 877–885 (2007).

National Institute of Mental Health. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). NIMHhttps://www.nimh.nih.gov/research-priorities/rdoc/index.shtml (accessed 25 Aug 2016).

Insel, T. R. The NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Project: precision medicine for psychiatry. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 395–397 (2014). This commentary describes the rationale for developing the RDoC.

Reynolds, C. F. & Frank, E. US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement on screening for depression in adults: not good enough. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 189–190 (2016).

Thombs, B. D., Ziegelstein, R. C., Roseman, M., Kloda, L. A. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. There are no randomized controlled trials that support the United States Preventive Services Task Force guideline on screening for depression in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Med. 12, 13 (2014).

O'Connor, E. et al. Screening for Depression in Adults: an Updated Systematic Evidence Review for the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016).

van Zoonen, K. et al. Preventing the onset of major depressive disorder: a meta-analytic review of psychological interventions. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 318–329 (2014).

Cleare, A. et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2008 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 459–525 (2015).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management. NICEhttps://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 (2016).

The Program for National Disease Management Guidelines (NVL). S3 guideline and National Care Guideline (NVL) Unipolar Depression. Versorgungsleitliniehttp://www.depression.versorgungsleitlinien.de (2015).

Gelenberg, A. J. A review of the current guidelines for depression treatment. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, e15 (2010).

Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., Andersson, G. & van Oppen, P. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 76, 909–922 (2008).

Cuijpers, P. et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive–behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can. J.Psychiatry 58, 376–385 (2013).

Linde, K. et al. Comparative effectiveness of psychological treatments for depressive disorders in primary care: network meta-analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 16, 103 (2015).

Luborsky, L., Singer, B. & Luborsky, L. Comparative studies of psychotherapies. Is it true that “everyone has won and all must have prizes”? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 32, 995–1008 (1975).

Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P. & Davis, M. K. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 68, 438–450 (2000).

Kim, D. M., Wampold, B. E. & Bolt, D. M. Therapist effects in psychotherapy: a random-effects modeling of the National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program data. Psychother. Res. 16, 161–172 (2006).

DeRubeis, R. J., Brotman, M. A. & Gibbons, C. J. A conceptual and methodological analysis of the nonspecifics argument. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 12, 174–183 (2005).

Cuijpers, P. Are all psychotherapies equally effective in the treatment of adult depression? The lack of statistical power of comparative outcome studies. Evid. Based Mental Health 19, 39–42 (2016).

Sotsky, S. M. et al. Patient predictors of response to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy: findings in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Am. J. Psychiatry 148, 997–1008 (1991).

Dimidjian, S. et al. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 74, 658–670 (2006).

Amick, H. R. et al. Comparative benefits and harms of second generation antidepressants and cognitive behavioral therapies in initial treatment of major depressive disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 351, h6019 (2015).

Weitz, E. S. et al. Baseline depression severity as moderator of depression outcomes between cognitive behavioral therapy versus pharmacotherapy: an individual patient data meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 1102–1109 (2015).

Hollon, S. D. et al. Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy versus medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 417–422 (2005). In a classic trial for treatment of depression, outcomes were not significantly different for patients receiving cognitive therapy versus pharmacotherapy. Among those who were successfully treated, patients who were withdrawn from cognitive therapy were significantly less likely to relapse during continuation than patients withdrawn from medications and no more likely to relapse than patients who kept taking medication.

Mohr, D. C. et al. Perceived barriers to psychological treatments and their relationship to depression. J. Clin. Psychol. 66, 394–409 (2010).

Mohr, D. C. et al. Barriers to psychotherapy among depressed and nondepressed primary care patients. Ann. Behav. Med. 32, 254–258 (2006).

Mohr, D. C., Vella, L., Hart, S., Heckman, T. & Simon, G. The effect of telephone-administered psychotherapy on symptoms of depression and attrition: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. (New York) 15, 243–253 (2008).

Mohr, D. C. et al. Effect of telephone-administered versus face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy on adherence to therapy and depression outcomes among primary care patients: a randomized trial. JAMA 307, 2278–2285 (2012).

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Depression: the NICE Guideline on the Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults: Updated Edition (British Psychological Society, 2010).

Huntley, A. L., Araya, R. & Salisbury, C. Group psychological therapies for depression in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 200, 184–190 (2012).

Mohr, D. C., Burns, M. N., Schueller, S. M., Clarke, G. & Klinkman, M. Behavioral intervention technologies: evidence review and recommendations for future research in mental health. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 35, 332–338 (2013).

Richards, D. & Richardson, T. Computer-based psychological treatments for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32, 329–342 (2012). This systematic review of technology-based interventions for MDD revealed moderate post-treatment effects relative to control conditions. Interventions that included support from a human coach yielded substantially better outcomes relative to self-directed interventions.

Ebert, D. D. et al. Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in youth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled outcome trials. PLoS ONE 10, e0119895 (2015).

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Computerised Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Depression and Anxiety (NICE, 2006).

Titov, N. et al. MindSpot Clinic: an accessible, efficient, and effective online treatment service for anxiety and depression. Psychiatr. Serv. 66, 1043–1050 (2015).

Mohr, D. C. et al. Trials of intervention principles: evaluation methods for evolving behavioral intervention technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 17, e166 (2015).

Saeb, S. et al. Mobile phone sensor correlates of depressive symptom severity in daily-life behavior: an exploratory study. J. Med. Internet Res. 17, e175 (2015).

Burns, M. N. et al. Harnessing context sensing to develop a mobile intervention for depression. J. Med. Internet Res. 13, e55 (2011).

Insel, T. Director's blog: quality counts. NIMHhttp://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/2015/quality-counts.shtml (2015).

Hyman, S. E. & Nestler, E. J. Initiation and adaptation: a paradigm for understanding psychotropic drug action. Am. J. Psychiatry 153, 151–162 (1996).

Hill, A. S., Sahay, A. & Hen, R. Increasing adult hippocampal neurogenesis is sufficient to reduce anxiety and depression-like behaviors. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 2368–2378 (2015).

Sharp, T. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of antidepressant action. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 14, 309–325 (2013).

Zohar, J. et al. A review of the current nomenclature for psychotropic agents and an introduction to the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 25, 2318–2325 (2015). This paper is an introduction and description of the new Neuroscience-based Nomenclature of psychotropic drugs.

Cipriani, A. et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 373, 746–758 (2009). This network meta-analysis compares all new antidepressant drugs in terms of their efficacy and tolerability.

Cassano, P. & Fava, M. Tolerability issues during long-term treatment with antidepressants. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 16, 15–25 (2004).

Ratti, E. et al. Full central neurokinin-1 receptor blockade is required for efficacy in depression: evidence from orvepitant clinical studies. J. Psychopharmacol. 27, 424–434 (2013).

Sanacora, G., Zarate, C. A., Krystal, J. H. & Manji, H. K. Targeting the glutamatergic system to develop novel, improved therapeutics for mood disorders. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 426–437 (2008).

Noto, C. et al. Targeting the inflammatory pathway as a therapeutic tool for major depression. Neuroimmunomodulation 21, 131–139 (2014).

Ehrich, E. et al. Evaluation of opioid modulation in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 1448–1455 (2015).

Fava, M. et al. A phase 1B, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled, multiple-dose escalation study of NSI-189 phosphate, a neurogenic compound, in depressed patients. Mol. Psychiatry http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.178 (2015).

Gallagher, P. et al. WITHDRAWN: antiglucocorticoid treatments for mood disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6, CD005168 (2015).

Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., Warmerdam, L. & Andersson, G. Psychotherapy versus the combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 26, 279–288 (2009).

Cuijpers, P., Dekker, J., Hollon, S. D. & Andersson, G. Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 70, 1219–1229 (2009).

Schatzberg, A. F. et al. Chronic depression: medication (nefazodone) or psychotherapy (CBASP) is effective when the other is not. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 513–520 (2005).

Fava, M. & Davidson, K. G. Definition and epidemiology of treatment-resistant depression. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 19, 179–200 (1996).

Berlim, M. T. & Turecki, G. Definition, assessment, and staging of treatment-resistant refractory major depression: a review of current concepts and methods. Can. J. Psychiatry 52, 46–54 (2007).

Gibson, T. B. et al. Cost burden of treatment resistance in patients with depression. Am. J. Manag. Care 16, 370–377 (2010).

De Carlo, V., Calati, R. & Serretti, A. Socio-demographic and clinical predictors of non-response/non-remission in treatment resistant depressed patients: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 240, 421–430 (2016).

Jakubovski, E., Varigonda, A. L., Freemantle, N., Taylor, M. J. & Bloch, M. H. Systematic review and meta-analysis: dose–response relationship of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in major depressive disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 174–183 (2016).

Hieronymus, F., Nilsson, S. & Eriksson, E. A mega-analysis of fixed-dose trials reveals dose-dependency and a rapid onset of action for the antidepressant effect of three selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Transl Psychiatry 6, e834 (2016).

Zhou, X. et al. Comparative efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of augmentation agents in treatment-resistant depression: systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76, e487–e498 (2015).

Zhou, X. et al. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation for treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 18, pyv060 (2015).

Trivedi, R. B., Nieuwsma, J. A., Williams, J. W. Jr & Baker, D. Evidence Synthesis for Determining the Efficacy of Psychotherapy for Treatment Resistant Depression (Department of Veterans Affairs (US), 2009).

Wiles, N. et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care based patients with treatment resistant depression: results of the CoBalT randomised controlled trial. Lancet 381, 375–384 (2013).

Wiles, N. J. et al. Long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for treatment-resistant depression in primary care: follow-up of the CoBalT randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 137–144 (2016).

Negt, P. et al. The treatment of chronic depression with cognitive behavioral analysis system of psychotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled clinical trials. Brain Behav. 6, e00486 (2016).

UK ECT Review Group. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 361, 799–808 (2003).

Spaans, H.-P., Kho, K. H., Verwijk, E., Kok, R. M. & Stek, M. L. Efficacy of ultrabrief pulse electroconvulsive therapy for depression: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 150, 720–726 (2013).

Gaynes, B. N. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 75, 477–489 (2014).

Ren, J. et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation versus electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 51, 181–189 (2014).

Bersani, F. S. et al. Deep transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment for psychiatric disorders: a comprehensive review. Eur. Psychiatry 28, 30–39 (2013).

Cretaz, E., Brunoni, A. R. & Lafer, B. Magnetic seizure therapy for unipolar and bipolar depression: a systematic review. Neural Plast. 2015, 521398 (2015).

Priori, A., Hallett, M. & Rothwell, J. C. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or transcranial direct current stimulation? Brain Stimul. 2, 241–245 (2009).

Meron, D., Hedger, N., Garner, M. & Baldwin, D. S. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in the treatment of depression: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 57, 46–62 (2015).

Rohan, M. L. et al. Rapid mood-elevating effects of low field magnetic stimulation in depression. Biol. Psychiatry 76, 186–193 (2014).

Rizvi, S. J. et al. Neurostimulation therapies for treatment resistant depression: a focus on vagus nerve stimulation and deep brain stimulation. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 23, 424–436 (2011).

Fitzgerald, P. B. Non-pharmacological biological treatment approaches to difficult-to-treat depression. Med. J. Aust. 199, S48–S51 (2013).

Coyle, C. M. & Laws, K. R. The use of ketamine as an antidepressant: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 30, 152–163 (2015).

Singh, J. B. et al. Intravenous esketamine in adult treatment-resistant depression: a double-blind, double-randomization, placebo-controlled study. Biol. Psychiatry 80, 424–431 (2016).

Papakostas, G. I., Mischoulon, D., Shyu, I., Alpert, J. E. & Fava, M. S-Adenosyl methionine (SAMe) augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors for antidepressant nonresponders with major depressive disorder: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 942–948 (2010).

Papakostas, G. I. et al. l-Methylfolate as adjunctive therapy for SSRI-resistant major depression: results of two randomized, double-blind, parallel-sequential trials. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 1267–1274 (2012).

Gertsik, L., Poland, R. E., Bresee, C. & Rapaport, M. H. Omega-3 fatty acid augmentation of citalopram treatment for patients with major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 32, 61–64 (2012).

Drevets, W. C., Zarate, C. A. & Furey, M. L. Antidepressant effects of the muscarinic cholinergic receptor antagonist scopolamine: a review. Biol. Psychiatry 73, 1156–1163 (2013).

Fava, M. et al. Opioid modulation with ALKS 5461 as adjunctive treatment for inadequate responders to antidepressants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 499–508 (2016).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U. S. workers. Am. J. Psychiatry 163, 1561–1568 (2006).

Rock, P. L., Roiser, J. P., Riedel, W. J. & Blackwell, A. D. Cognitive impairment in depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 44, 2029–2040 (2014).

Peckham, A. D., McHugh, R. K. & Otto, M. W. A meta-analysis of the magnitude of biased attention in depression. Depress. Anxiety 27, 1135–1142 (2010).

Lee, R. S., Hermens, D. F., Porter, M. A. & Redoblado-Hodge, M. A. A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in first-episode major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 140, 113–124 (2012).

Bora, E., Harrison, B. J., Yucel, M. & Pantelis, C. Cognitive impairment in euthymic major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 43, 2017–2026 (2013).

McDermott, L. M. & Ebmeier, K. P. A meta-analysis of depression severity and cognitive function. J. Affect. Disord. 119, 1–8 (2009).

Zaninotto, L. et al. Cognitive markers of psychotic unipolar depression: a meta-analytic study. J. Affect. Disord. 174, 580–588 (2015).

Evans, V. C., Iverson, G. L., Yatham, L. N. & Lam, R. W. The relationship between neurocognitive and psychosocial functioning in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 75, 1359–1370 (2014).

Rosenblat, J. D., Kakar, R. & McIntyre, R. S. The cognitive effects of antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 19, pyv082 (2015).

Turecki, G. & Brent, D. A. Suicide and suicidal behaviour. Lancet 387, 1227–1239 (2016).

Meerwijk, E. L. et al. Direct versus indirect psychosocial and behavioural interventions to prevent suicide and suicide attempts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 544–554 (2016).

Pirkis, J. et al. Interventions to reduce suicides at suicide hotspots: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2, 994–1001 (2015).

Sharma, T., Guski, L. S., Freund, N. & Gotzsche, P. C. Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports. BMJ 352, i65 (2016).

Braun, C., Bschor, T., Franklin, J. & Baethge, C. Suicides and suicide attempts during long-term treatment with antidepressants: a meta-analysis of 29 placebo-controlled studies including 6,934 patients with major depressive disorder. Psychother. Psychosom. 85, 171–179 (2016).

Stone, M. et al. Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration. BMJ 339, b2880 (2009).

Friedman, R. A. & Leon, A. C. Expanding the black box — depression, antidepressants, and the risk of suicide. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 2343–2346 (2007).

Friedman, R. A. Antidepressants' black-box warning—10 years later. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1666–1668 (2014).

Patel, V. et al. Addressing the burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet 387, 1672–1685 (2016).

Gureje, O., Kola, L. & Afolabi, E. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder in elderly Nigerians in the Ibadan Study of Ageing: a community-based survey. Lancet 370, 957–964 (2007).

World Health Organization. WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). WHOhttp://www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap/en/ (2016).

Taylor, W. D., Aizenstein, H. J. & Alexopoulos, G. S. The vascular depression hypothesis: mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Mol. Psychiatry 18, 963–974 (2013).

Jokela, M., Hamer, M., Singh-Manoux, A., Batty, G. D. & Kivimä ki, M. Association of metabolically healthy obesity with depressive symptoms: pooled analysis of eight studies. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 910–914 (2014).

Vogelzangs, N. et al. Metabolic depression: a chronic depressive subtype? Findings from the InCHIANTI study of older persons. J. Clin. Psychiatry 72, 598–604 (2011).

Miller, A. H. & Raison, C. L. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 22–34 (2015).

Nemeroff, C. B. et al. Differential responses to psychotherapy versus pharmacotherapy in patients with chronic forms of major depression and childhood trauma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14293–14296 (2003).

McGrath, C. L. et al. Toward a neuroimaging treatment selection biomarker for major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 821–829 (2013).

Uher, R. et al. An inflammatory biomarker as a differential predictor of outcome of depression treatment with escitalopram and nortriptyline. Am. J. Psychiatry 171, 1278–1286 (2014).

Raison, C. L. et al. A randomized controlled trial of the tumor necrosis factor antagonist infliximab for treatment-resistant depression: the role of baseline inflammatory biomarkers. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 31–41 (2013).

Arnow, B. A. et al. Depression subtypes in predicting antidepressant response: a report from the iSPOT-D trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 172, 743–750 (2015).

Insel, T. R. & Cuthbert, B. N. Medicine. Brain disorders? Precisely. Science 348, 499–500 (2015).

Weinberger, D. R., Glick, I. D. & Klein, D. F. Whither Research Domain Criteria (RDoC)?: The good, the bad, and the ugly. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 1161–1162 (2015).

King, M. et al. Development and validation of an international risk prediction algorithm for episodes of major depression in general practice attendees: the PredictD study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 65, 1368–1376 (2008).

Nestler, E. J. & Hyman, S. E. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1161–1169 (2010).

Sun, H., Kennedy, P. J. & Nestler, E. J. Epigenetics of the depressed brain: role of histone acetylation and methylation. Neuropsychopharmacology 38, 124–137 (2013).

Gaiteri, C., Ding, Y., French, B., Tseng, G. C. & Sibille, E. Beyond modules and hubs: the potential of gene coexpression networks for investigating molecular mechanisms of complex brain disorders. Genes Brain Behav. 13, 13–24 (2014).

Cryan, J. F. & Dinan, T. G. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 701–712 (2012).

Duman, R. S. & Aghajanian, G. K. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science 338, 68–72 (2012).

Chattarji, S., Tomar, A., Suvrathan, A., Ghosh, S. & Rahman, M. M. Neighborhood matters: divergent patterns of stress-induced plasticity across the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1364–1375 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Introduction (C.O.); Epidemiology (B.W.P.); Mechanisms/pathophysiology (C.O., S.M.G., B.W.P., C.M.P. and A.E.); Diagnosis, screening and prevention (A.F.S.); Management (M.F. and D.C.M.); Quality of life (S.M.G.); Outlook (C.O. and A.F.S.); Overview of the Primer (C.O.).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.O. has received honoraria for lectures from Lundbeck and Servier and for membership in a scientific advisory board from Lundbeck and Neuraxpharm. S.M.G. has received honoraria from Novartis and travel reimbursements from Novartis, Merck Serono and Biogen Idec and has received in-kind research support for conducting clinical trials from GAIA AG, a commercial developer and vendor of health care management and eHealth interventions. B.W.P. has received research funding from Jansen Research and is supported by a VICI grant from the Dutch Scientific Organization. C.M.P. was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre in Mental Health at South London, Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London, the grants ‘Persistent fatigue induced by interferon-α: A New Immunological Model for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome’ (MR/J002739/1), and ‘Immuno-psychiatry: a consortium to test the opportunity for immunotherapeutics in psychiatry’ (MR/L014815/1) from the Medical Research Council (UK), research funding from the Medical Research Council (UK) and the Wellcome Trust for research on depression and inflammation as part of two large consortia that also include Johnson & Johnson, GSK, Lundbeck and Pfizer, and research funding from Johnson & Johnson as part of a programme of research on depression and inflammation. In addition, C.M.P. has received a speaker's fee from Lundbeck. A.E. has received research funding from Brain Resource, Inc. and honoraria for consulting from Otsuka, Acadia and Takeda. M.F. reports the following research support: Abbot Laboratories; Alkermes, Inc.; American Cyanamid; Aspect Medical Systems; AstraZeneca; Avanir Pharmaceuticals; BioResearch; BrainCells Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb; CeNeRx BioPharma; Cephalon; Cerecor; Clintara, LLC; Covance; Covidien; Eli Lilly and Company; EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Euthymics Bioscience, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; FORUM Pharmaceuticals; Ganeden Biotech, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Harvard Clinical Research Institute; Hoffman-LaRoche; Icon Clinical Research; i3 Innovus/Ingenix; Janssen R&D, LLC; Jed Foundation; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development; Lichtwer Pharma GmbH; Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Lundbeck Inc.; MedAvante; Methylation Sciences Inc.; National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression (NARSAD); National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM); National Coordinating Center for Integrated Medicine (NiiCM); National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); Neuralstem, Inc.; Novartis AG; Organon Pharmaceuticals; PamLab, LLC.; Pfizer Inc.; Pharmacia-Upjohn; Pharmaceutical Research Associates., Inc.; Pharmavite® LLC; PharmoRx Therapeutics; Photothera; Reckitt Benckiser; Roche Pharmaceuticals; RCT Logic, LLC (formerly Clinical Trials Solutions, LLC); Sanofi-Aventis US LLC; Shire; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI); Synthelabo; Takeda Pharmaceuticals; Tal Medical; Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories; Advisory Board/ Consultant: Abbott Laboratories; Acadia; Affectis Pharmaceuticals AG; Alkermes, Inc.; Amarin Pharma Inc.; Aspect Medical Systems; Auspex Pharmaceuticals; Avanir Pharmaceuticals; AXSOME Therapeutics; Bayer AG; Best Practice Project Management, Inc.; Biogen and BioMarin Phar. D.C.M. has received honoraria for lectures and for membership in a scientific advisory board from Otsuka. A.F.S. has, since 2015, served as a consultant for Alkermes, Cervel, Clintara, Forum Pharmaceuticals, McKinsey and Company, Myriad Genetics, Neurontics, Naurex, One Carbon, Pfizer, Takeda, Sunovion and X-Hale and as a speaker for Pfizer; he holds equity in Amnestix, Cervel, Corcept (co-founder), Delpor, Gilead Incyte, Merck, Neurocrine, Seattle Genetics, Titan and X-Hale; and he is listed as an inventor on pharmacogenetic and antiglucocorticoid use patents on prediction of antidepressant response.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Otte, C., Gold, S., Penninx, B. et al. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2, 16065 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.65

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.65

This article is cited by

-

Screening for depression in children and adolescents in primary care or non-mental health settings: a systematic review update

Systematic Reviews (2024)

-

Serum levels of interleukin-33 and mesencephalic astrocyte derived neurotrophic factors in patients with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional comparative design

BMC Psychiatry (2024)

-

The moderating effect of psychological distress in the association between temperaments and dark future among young adults

BMC Psychiatry (2024)

-

Knowledge, attitude, and practice of patients with major depressive disorder on exercise therapy

BMC Public Health (2024)

-

Targeting suicidal ideation in major depressive disorder with MRI-navigated Stanford accelerated intelligent neuromodulation therapy

Translational Psychiatry (2024)