Abstract

PP2ACdc55 is a highly conserved serine-threonine protein phosphatase that is involved in diverse cellular processes. In budding yeast, meiotic cells lacking PP2ACdc55 activity undergo a premature exit from meiosis I which results in a failure to form bipolar spindles and divide nuclei. This defect is largely due to its role in negatively regulating the Cdc Fourteen Early Anaphase Release (FEAR) pathway. PP2ACdc55 prevents nucleolar release of the Cdk (Cyclin-dependent kinase)-antagonising phosphatase Cdc14 by counteracting phosphorylation of the nucleolar protein Net1 by Cdk. CDC55 was identified in a genetic screen for monopolins performed by isolating suppressors of spo11Δ spo12Δ lethality suggesting that Cdc55 might have a role in meiotic chromosome segregation. We investigated this possibility by isolating cdc55 alleles that suppress spo11Δ spo12Δ lethality and show that this suppression is independent of PP2ACdc55’s FEAR function. Although the suppressor mutations in cdc55 affect reductional chromosome segregation in the absence of recombination, they have no effect on chromosome segregation during wild type meiosis. We suggest that Cdc55 is required for reductional chromosome segregation during achiasmate meiosis and this is independent of its FEAR function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Meiosis is a specialised form of cell division in sexually reproducing organisms by which haploid daughter cells are produced from diploid germ cells. This is different from mitotic cycle in which daughter cells produced have the same DNA content as their parental cells1,2. Meiotic cells execute two nuclear divisions (meiosis I and II) following a single round of DNA replication. Four crucial innovations during meiosis help to achieve the remarkable feat of halving ploidy1,2. Firstly, reciprocal recombination and formation of chiasmata between homologous chromosomes occur during prophase I. Secondly, sister kinetochores are mono-oriented on the meiosis I spindle. Thirdly, centromeric cohesion is protected during meiosis I i.e., cohesion is destroyed distal (but not proximal) to chiasmata. Cohesion is preserved around centromeres until meiosis II to help dyad chromosomes to bi-orient on the meiosis II spindle. Finally, DNA replication is inhibited between meiosis I and meiosis II.

Insights into the mechanism of monopolar attachment have largely come from research with budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe). In S. cerevisiae, monopolar attachment is dependent on monopolin complex which consists of four subunits namely Mam1, Csm1, Lrs4 and Hrr25. Cells lacking any of these components bi-orient sister centromeres during meiosis I and attempt to separate sister chromatids3,4,5. While Mam1 is meiosis-specific3, the casein kinase Hrr25 and nucleolar proteins Csm1 and Lrs4 are expressed during both mitosis and meiosis I & II4,5. Csm1 and Lrs4 remain in the nucleolus during most of mitotic cell cycle and are released only during meiosis I by polo kinase Cdc54,6. Following nucleolar release, Lrs4 is hyperphosphorylated by Dbf4-dependent kinase Cdc7 and Cdc5/Spo137. Hyperphosphorylation of Lrs4 promotes monopolin’s association with kinetochores. Monopolin’s binding to kinetochores and function is dependent on a physical interaction between Csm1 and Dsn1, a component of the MIND complex8,9.

PP2A belongs to a highly conserved family of serine-threonine phosphatases involved in diverse cellular processes. PP2A phosphatase consists of 3 subunits-a catalytic subunit (Pph21/Pph22), a scaffold subunit (Tpd3) and a regulatory subunit (Rts1/Cdc55). PP2ACdc55 refers to a form that contains Pph21/22, Tpd3 and Cdc55. CDC55 gene was isolated in a genetic screen for monopolin genes4. However the extremely poor growth of cdc55Δ cells precluded analysis of PP2ACdc55’s role in monopolar attachment. Phenotypic analyses of strains bearing a meiotic null allele of CDC55 (PCLB2-CDC55) revealed that PP2ACdc55 is required for preventing premature exit from meiosis I10,11. During mitosis and meiosis I, PP2ACdc55 prevents Cdc14 release from the nucleous by counteracting phosphorylation of Net1 by Cdk10,11,12. During meiosis, PCLB2-CDC55 cells release Cdc14 prematurely from the nucleolus, fail to form bipolar spindles and do not undergo meiotic divisions10. A form of Net1 that lacks 6 Cdk phosphorylation sites (net1-6Cdk) suppresses the nuclear division defect of PCLB2-CDC55 cells10. However the spore viability of net1-6Cdk PCLB2-CDC55 cells is reduced compared to NET1 and net1-6Cdk cells10, leaving open the possibility that PP2ACdc55 might play a role in meiotic chromosome segregation.

To assess PP2ACdc55’s role in meiotic chromosome segregation, we performed a genetic screen and isolated two classes of suppressor mutations within the CDC55 ORF. Class A mutants suppressed the dyad phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains. Class B mutants rescued the poor spore viability phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains. We show that the Class A mutations affect the FEAR function of Cdc55 confirming the antagonistic roles of Cdc55 and Spo12 in the FEAR pathway. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the Class B mutations affect reductional segregation of sister centromeres during achiasmate meiosis but not during wild type meiosis. We suggest that PP2ACdc55 is required for reductional chromosome segregation in the absence of recombination and that this function is distinct from its role in the FEAR pathway.

Results

Mutations in CDC55 suppress the poor spore viability and dyad phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains

The inability of PCLB2-CDC55 cells to form tetrads is partially suppressed by net1-6Cdk10. However the spore viability of PCLB2-CDC55 net1-6Cdk cells was around 50% compared to around 90% for NET1 and net1-6Cdk cells10. Reduced spore viability could be due to incomplete suppression of PCLB2-CDC55 by net1-6Cdk. Alternatively, PP2ACdc55 may have a role in accurate meiotic chromosome segregation that is distinct from its FEAR function. Interestingly, CDC55 was isolated in a genetic screen for monopolin mutants4. To determine Cdc55’s role in meiotic chromosome segregation, we isolated ‘monopolin’ alleles of CDC55. We targeted the CDC55 open reading frame (ORF) to PCR-based mutagenesis and selected for mutants that suppress the low spore viability of the spo11Δ spo12Δ diploids. Deletion of both SPO11 and SPO12 is marked by severely low spore viability due to co-segregation of sister centromeres without bi-orientation of homologues4. SPO11 is a meiosis-specific gene that initiates meiotic recombination by catalysing the formation of DNA double-strand breaks13. Spo12 is a nucleolar protein required for Cdc14 for exit from meiosis I and its absence during meiosis results in production of dyads14. Inactivating monopolar attachment in a spo11Δ spo12Δ genetic background causes sister centromeres to segregate equationally and increases spore viability (Fig. 1a)4. A library of CDC55 mutant alleles was generated by random PCR mutagenesis followed by gap-repair in spo11Δ spo12Δ cdc55Δ cells (Fig. 1b). The transformants were induced to sporulate by transferring them to Sporulation Medium (SPM). Microscopic examination of spores surprisingly revealed generation of mutations that suppressed the dyad phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains i.e. the mutants formed tetrads. Transformants with high spore viability were selected using the ether-killing assay15. Exposure to ether vapours preferentially kills vegetative cells but not spores. This genetic screen thus identified two classes of cdc55 mutants (Fig. 1c). Class A- These suppressed the dyad but not the spore inviability phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains. Class B- they suppressed the spore inviability phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains.

(a) spo11Δ spo12Δ cells form inviable aneuploid dyads due to reductional segregation of sister chromatids during anaphase I (top panel). Disabling monopolar attachment in spo11Δ spo12Δ cells results in equational segregation of sister chromatids and production of viable euploid dyads (bottom panel). Anaphase I segregation of two pairs of non-homologous sister chromatids (in red and blue) with kinetochores (as black circles) and spindle (as a black line) is depicted in the schematic. (b) spo11Δ spo12Δ cdc55Δ cells were transformed using with a library of cdc55 mutant alleles generated by random PCR mutagenesis followed by gap-repair mediated transformation. (c) Screen generated two classes of mutants. Class A mutants suppressed the spo12Δ dyad phenotype and were identified by dark-field microscopy. Class B mutants (monopolin) produced viable spores as determined by performing the ether-killing based spore viability assay.

Suppressors of spo12Δ dyad phenotype

To test whether the suppression of dyad phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ was due to mutations within the CDC55 gene, the plasmids bearing CDC55 genes were recovered from the mutants and re-introduced into the parental spo11Δ spo12Δ cdc55Δ strain. Eight alleles (T1-T8) were selected that produced the highest count of tetrads. Figure 2a shows the composition of asci from diploid spo11Δ spo12Δ cdc55Δ strains with these 8 alleles. While spo11Δ spo12Δ cdc55Δ cells transformed with a plasmid encoding wild-type CDC55 produced 100% dyads like spo12Δ strains, transformants with the eight mutant alleles formed tetrads at frequencies ranging from 40–62% (Fig. 2a). Representative images of asci formed by spo11Δ spo12Δ cells carrying either wild type CDC55 or the tetrad-forming allele of CDC55 (T5) are shown in the Supplementary Figure S1. Plasmids bearing mutant cdc55 alleles were isolated from these strains and sequenced to identify mutations that caused suppression of the dyad phenotype. The effect of mutations identified in the 8 alleles on the Cdc55 a.a. sequence are shown in Table 1.

(a) Class A mutations in cdc55 partially suppress the spo11Δ spo12Δ dyad phenotype. Eight alleles that suppressed dyad phenotype are labelled T1-8 (T = tetrad-forming allele) (N = 100). (b) cdc55-T5 suppresses the nuclear division defect of spo12Δ cells. CDC55 SPO12, CDC55 spo12Δ, cdc55-T5 SPO12, cdc55-T5 spo12Δ cells were induced to sporulate by transferring them to SPM and incubating for 12 hours in a shaker at 30 °C. Cells were stained with DAPI and classified as either mononucleate, binucleate or tri/tetra-nucleate (N = 100). (c) Frequency of lte1Δ spo12Δ haploids produced from sporulation followed by tetrad dissection (216 tetrads each in triplicates) and germination of LTE1/lte1Δ SPO12/spo12Δ diploids carrying either CDC55 or cdc55-T5. Difference in the frequencies between CDC55 and cdc55-T5 strains is statistically significant (Student’s t-test, P < 0.01). (d) PMET3-CDC20 cells carrying either CDC55 or cdc55Δ or cdc55-T5 were transferred to SD medium in the presence of methionine and incubated for 160 minutes. Cells were fixed and subjected to immunostaining with anti-Cdc14 antibodies. DNA was visualized by staining with DAPI. Percentage of cells with nucleolar Cdc14 and released Cdc14 signals were calculated (N = 100). Representative images of cells with nucleolar and released Cdc14 signals are shown. (e) cdc55-T5 NET1 spo12Δ and cdc55-T5 net1-6Cdk spo12Δ strains were induced to sporulate by transferring them to SPM followed by incubation for 24 h. Spores were harvested and nuclear division was scored by staining with DAPI (N = 100). (f) Antagonistic roles of PP2ACdc55 and Spo12 in the regulation of FEAR pathway.

cdc55-T5 suppresses the nuclear division defect of spo12Δ strains

We chose the cdc55-T5 for further analysis as this was consistently the best suppressor of spo11Δ spo12Δ dyad phenotype. We integrated the cdc55-T5 allele at its endogenous locus by homologous recombination. To test whether cdc55-T5 suppresses the nuclear division defect of spo12Δ, the CDC55 spo12Δ and cdc55-T5 spo12Δ strains were induced to sporulate by transferring them to SPM. While CDC55 spo12Δ formed 90% binucleates but no tri/tetra-nucleates after 11 hours in SPM, the cdc55-T5 spo12Δ cells formed 60% tri/tetra-nucleates (Fig. 2b).

cdc55-T5 suppresses spo12Δ lte1Δ lethality

cdc55-T5 suppression of spo12Δ dyad phenotype can be explained on basis of opposing roles of PP2ACdc55 and Spo12 in FEAR regulation (Fig. 2f)16. Spo12 is a positive regulator of the FEAR pathway. Following Cdk-mediated phosphorylation, Spo12 helps in dissociation of the Replication Fork Barrier protein (Fob1) which stabilizes Net1-Cdc14 interaction17,18. On the other hand, PP2ACdc55 has an antagonistic role in the FEAR pathway12. It opposes Net1 phosphorylation by Cdk during metaphase and prevents Cdc14 release from the nucleolus12. Therefore the inability of spo12Δ cells to exit from meiosis I due to the lack of Cdc14 release might be suppressed by cdc55 mutations. If this idea were to be true one would predict the cdc55-T5 strains to be defective in preventing Cdc14 release from the nucleolus.

We first tested whether cdc55-T5 suppressed the synthetic lethality of spo12Δ and lte1Δ strains. Lte1 is part of the mitotic exit network (MEN) that causes a complete release of Cdc14 release during anaphase19,20. Synthetic lethality of spo12Δ and lte1Δ strains is due to the failure of spo12Δ lte1Δ strains to release Cdc14 from the nucleolus and exit from mitosis. Thus any mutation that increases Cdc14 release is expected to suppress the lethality of spo12Δ lte1Δ strains. We therefore mated MATa lte1Δ strains with MATα spo12Δ strains that contained either CDC55 or cdc55-T5 alleles. The diploids thus generated were sporulated. Hundred spores were dissected onto rich medium plates and haploids from viable spores were genotyped for segregation of lte1Δ, spo12Δ and CDC55/cdc55-T5 markers. As expected, we failed to obtain any lte1Δ spo12Δ CDC55 cells (frequency < 0.46%) indicating that spo12Δ is synthetic lethal with lte1Δ. In contrast, we obtained cdc55-T5 lte1Δ spo12Δ strains (frequency = 4.77%) indicating that cdc55-T5 suppresses spo12Δ lte1Δ lethality and causes increased release of Cdc14 from the nucleolus (Fig. 2c).

cdc55-T5 cells release Cdc14 prematurely from the nucleolus

To directly test whether cdc55-T5 cells are defective in preventing Cdc14 release from the nucleolus we constructed PMET3-CDC20 strains containing either wild type CDC55 or cdc55-T5 or cdc55Δ. Cdc20, an activator of APC (Anaphase Promoting Complex), can be depleted from PMET3-CDC20 strains by addition of methionine to the medium. After 160 minutes of incubation of the 3 strains in SD medium containing methionine, Cdc14 localization was detected by immunostaining with anti-Cdc14 antibodies. In CDC55 cells, only 18% of cells had Cdc14 released from the nucleolus. In contrast, about 95% of cdc55Δ cells and 81% of cdc55-T5 cells released Cdc14 from the nucleolus (Fig. 2d). If enhanced phosphorylation of Net1 by Cdk in cdc55-T5 cells was responsible for suppression of spo12Δ dyad phenotype, then net1-6Cdk should negate the suppression. To test this we generated cdc55-T5 spo12Δ diploid strains with wild type NET1 or net1-6Cdk. While cdc55-T5 spo12Δ NET1 strains formed around 68% tetrads and 22% dyads, cdc55-T5 spo12Δ net1-6Cdk cells formed 84% dyads and 2% tetrads (Fig. 2e). Taken together, our results indicate that mutations in CDC55 that suppress spo12Δ dyad phenotype are defective in restraining Cdc14 in the nucleolus.

Class B mutants -monopolin alleles of CDC55

In contrast to Class A mutants, Class B mutants partially suppressed the spore inviability phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains. They also suppressed the dyad phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains to variable extents. This suggests that the class B mutations affect a function of PP2ACdc55 that is distinct from its role in the FEAR pathway. In the genetic screen described above, we obtained seventeen class B mutants that had high spore viability (Fig. 1c). In order to confirm whether the high spore viability phenotype was caused due to mutations within the CDC55 ORF, plasmids were isolated from the 17 mutant strains and re-introduced into the parent spo11Δ spo12Δ cdc55Δ strain. This secondary screen confirmed the high spore viability phenotype of 7 alleles named cdc55-MP1 to cdc55-MP7 (Fig. 3a). Primers designed across the CDC55 open reading frame (ORF) were used to sequence the mutations within the 7 alleles. The effect of these mutations on Cdc55 a.a. sequence is presented in Table 2. To maximize the severity of the phenotype we combined the cdc55-MP1 and cdc55-MP4 mutations to create an allele cdc55-MP which we used for further analysis.

(a) spo11Δ spo12Δ cdc55Δ cells carrying plasmids encoding either wild type CDC55 or class B mutant cdc55 alleles (MP1-7) were sporulated. Spore viability was assessed using the ether-killing assay. spo11Δ spo12Δ and spo11Δ spo12Δ mam1Δ strains served as negative and positive controls respectively. (b) spo11Δ spo12Δ cells and spo11Δ spo12Δ strains carrying either mam1Δ or CDC55 or cdc55-T5 or cdc55-MP or cdc55-MP net1-6Cdk were induced to sporulate by transferring them to SPM followed by incubation for 24 h. Spores were harvested and nuclear division was scored by staining with DAPI (N = 100). Spore viability was determined by dissecting dyads onto YPD plates and grown at 30 °C. Spore viability (n = 100) was scored after 3 days.

Suppression of spo11Δ spo12Δ lethality by cdc55-MP is independent of PP2ACdc55’s FEAR function

To determine whether impairing Cdc55’s FEAR function suppresses the spo11Δ spo12Δ lethality, we tested the ability of cdc55-T5 to suppress spo11Δ spo12Δ lethality. The spore viabilities of dyads produced by CDC55 spo11Δ spo12Δ and cdc55-T5 spo11Δ spo12Δ cells were 2 and 4% respectively compared to 31% for cdc55-MP spo11Δ spo12Δ cells (Fig. 3b). Tetrads obtained from cdc55-MP cells had low spore viability (4.2%), which is expected as the second meiotic division will be random in these cells. Since the cdc55-T5 mutant is defective in preventing Cdc14 release (see above), our results suggest that a defect in Cdc55’s FEAR function per se is not sufficient to rescue the poor spore viability of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains. However the cdc55-MP allele also partially suppressed spo12Δ dyad phenotype (Fig. 3a). This leaves open the possibility that a FEAR defect in Cdc55 might contribute to suppression of spo11Δ spo12Δ spore inviability phenotype. Since net1-6Cdk suppresses the nuclear division defect of PCLB2-CDC55 cells10 and cdc55-T5 cells (see above), we generated cdc55-MP spo11Δ spo12Δ net1-6Cdk strains to overcome the FEAR defect of cdc55-MP cells. Indeed, cdc55-MP spo11Δ spo12Δ net1-6Cdk cells formed 100% dyads suggesting that net1-6Cdk suppressed the FEAR defect of cdc55-MP cells (Fig. 3a). However the spore viability of cdc55-MP spo11Δ spo12Δ net1-6Cdk cells was still high (35%) indicating that the FEAR defect in cdc55-MP cells does not contribute to suppression of spo11Δ spo12Δ spore lethality phenotype (Fig. 3b).

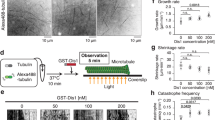

cdc55-MP affects reductional chromosome segregation during achiasmate meiosis

We investigated whether cdc55-MP affects reductional segregation of chromosomes in spo11Δ spo12Δ cells by analyzing segregation of sister centromeres in CDC55 spo11Δ spo12Δ and cdc55-MP spo11Δ spo12Δ cells. To visualize chromosome segregation, we tagged the URA3 locus (located 30 kb from the centromere) in one of the two parental chromosome V’s with GFP using the tetO/TetR system. CDC55 spo11Δ spo12Δ and cdc55-MP spo11Δ spo12Δ cells were induced to enter meiosis by transferring them into SPM. In the absence of recombination, homologs are not connected and segregate randomly. However sister centromeres are mono-oriented and move towards the same spindle pole. Consistent with this, in CDC55 spo11Δ spo12Δ cells, about 97% of URA3-GFP dots segregated reductionally (Fig. 4a). In contrast, about 80% of URA3-GFP dots segregated equationally in cdc55-MP spo11Δ spo12Δ cells (Fig. 4a). This suggests that PP2ACdc55 is required for reductional segregation of sister chromatids during achiasmate meiosis.

(a) CDC55 spo11Δ spo12Δ and cdc55-MP spo11Δ spo12Δ cells containing heterozygous GFP-tagged URA3 sequences were induced to enter meiosis by transferring them into SPM followed by incubation at 30 °C for 24 h. Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI to visualize DNA and segregation of GFP-tagged URA3 dots was assayed by fluorescence microscopy (N = 200). Representative images of dyads showing equational and reductional segregation of URA3-GFP sequences are depicted on the right. (b) Detection of homozygous URA3-GFP and DNA in tetrads produced by CDC55, cdc55-MP and mam1Δ strains. Tetrads produced by the strains were dissected onto YPD plates and grown at 30 °C. Spore viability (n = 100) was scored after 3 days. (c,d) Analysis of meiosis in CDC55 and cdc55-MP cells containing heterozygous URA3-GFP. Samples of cultures at indicated time points were taken out, fixed and stained with DAPI and anti-tubulin antibodies. (c) Kinetics of meiotic nuclear division shown by percentage of mononucleate, binucleate and tri/tetranucleate cells during the time course. (d) Proportion of cells containing anaphase I spindles undergoing reductional and equational segregation of URA3-GFP dots are depicted (N = 100 in triplicates). Difference in the frequencies of reductional segregation between CDC55 and cdc55-MP strains is not statistically significant (Student’s t-test, P < 0.1). Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments.

cdc55-MP does not affect chromosome segregation during wild type meiosis

We then tested whether cdc55-MP affects chromosome segregation during wild type meiosis. We monitored chromosome segregation in CDC55 and cdc55-MP cells by tagging homologous chromosomes with GFP and observing their segregation into tetranucleate cells. We used mam1Δ cells as a control. While mam1Δ cells missegregated chromosomes and produced inviable spores, CDC55 and cdc55-MP cells segregated chromosomes normally and produced viable spores (Fig. 4b). We also monitored the kinetics of nuclear division and segregation of GFP-tagged URA3 dots in wild type and cdc55-MP cells during meiosis I. cdc55-MP cells underwent 2 rounds of nuclear division albeit with somewhat delayed kinetics compared to wild type cells (Fig. 4c). However, there was no difference in the extent of reductional segregation of URA3-GFP dots between wild type and cdc55-MP cells (Fig. 4d). Taken together our results suggest that cdc55-MP has no major effect on chromosome segregation during wild type meiosis.

Ability of cdc55-MP to suppress spo11Δ spo12Δ spore lethality is recessive and not due to premature Clb3 expression or spindle checkpoint function

Cyclin Clb3 is transcribed during meiosis I but translated during meiosis II21. Expression of Clb3 during meiosis I affects monopolar attachment and protection of centromeric cohesion21. To test whether premature expression of Clb3 could cause the reductional chromosome defect of cdc55-MP spo11Δ cells we tested the effect of clb3Δ on the ability of cdc55-MP to suppress the poor spore viability phenotype of spo11Δ spo12Δ strains. Both spo11Δ spo12Δ cdc55-MP clb3Δ and spo11Δ spo12Δ cdc55-MP CLB3 strains had comparable spore viabilities indicating that ability of cdc55-MP to suppress spo11Δ spo12Δ is not due to premature expression of Clb3 during meiosis (Fig. 5). In the absence of recombination, sister centromeres segregate towards the same spindle pole, although the sister kinetochores are not under tension. This suggests that the meiotic checkpoint machinery does not correct such kinetochore-microtubule connections. It was formally possible that the inability of the spindle checkpoint to correct monopolar attachments was dependent on PP2ACdc55 and cdc55-MP affected this process. However, deletion of the gene encoding the Spindle Checkpoint component MAD2 had no effect on the ability of cdc55-MP to suppress spo11Δ spo12Δ lethality (Fig. 5). We also ruled out the possibility that cdc55-MP was a gain-of-function mutation as its effect on spo11Δ spo12Δ spore lethality was recessive (Fig. 5).

Discussion

PP2ACdc55 is a highly conserved protein phosphatase that is involved in diverse biological processes. We previously reported that PP2ACdc55 is required for preventing premature exit from meiosis I by counteracting phosphorylation of Net1 by Cdk. However it left open the possibility that PP2ACdc55 might have an additional role in meiotic chromosome segregation. By targeting the CDC55 ORF to PCR mutagenesis, we isolated mutant cdc55 alleles that either suppressed the spo12Δ dyad phenotype or suppressed spo11Δ spo12Δ lethality.

Suppressors of spo12Δ dyad phenotype are defective in restraining Cdc14 in the nucleolus during metaphase and confirm the antagonistic roles of Spo12 and PP2ACdc55 in the FEAR pathway. Spo12 mutants fail to release Cdc14 from the nucleolus resulting in an inability to undergo exit from meiosis I and consequently form dyads22,23. On the other hand, meiotic cells lacking PP2ACdc55 release Cdc14 prematurely from the nucleolus, undergo precocious exit from meiosis I and form monads10. We suggest that Class A mutations are hypomorphic alleles of cdc55 that result in Cdc14 release that is sufficient to rescue the spo12Δ dyad phenotype but not high enough to cause a premature exit from meiosis I. It will be interesting to test whether Class A mutations affect interaction of PP2ACdc55 with Net1, its putative substrate in the FEAR pathway.

Suppressors of spo11Δ spo12Δ lethality affect reductional chromosome segregation in recombination-deficient cells but had no noticeable effect in recombination-proficient cells. We further demonstrate that suppression of spo11Δ spo12Δ spore lethality is not due to loss of PP2ACdc55’s FEAR function. It has been reported that chiasmata promotes efficient monopolar attachment of sister kinetochores during meiosis I in fission yeast cells24,25. Although, chiasmata in budding yeast are dispensable for monopolar attachment3, they may modestly promote sister kinetochore co-orientation, which is not apparent in wild type cells but detectable in cdc55-MP cells. It is also possible that cdc55-MP allele is defective in pericentromeric cohesion which may facilitate bi-orientation of sister centromeres during achiasmate meiosis, However the presence of chiasmata might suppress this defect in cdc55-MP cells possibly by physically constraining the sister kinetochores to face the same spindle pole or by creating tension across centromeric regions. Comparing the binding partners of CDC55 and cdc55-MP encoded proteins and phosphorylation status of monopolin (and related proteins) during meiosis in CDC55 and cdc55-MP strains will be informative. In male Drosophila melanogaster, meiosis takes place without any recombination26. As PP2ACdc55 is a highly conserved phosphatase, it would be interesting to test whether it has any role during achiasmate meiosis in Drosophila males.

Methods

All strains used are derivatives of the SK1 strain and are indicated in Table S1. Meiotic cultures and in situ analysis were performed as described previously9,10. YCp50 plasmid encoding CDC55 was a gift from Prof. Tamar Kleinberger27. Mutagenic PCR followed by gap-repair mediated transformation was performed as described earlier5. Details of primers used for mutagenic PCR are available upon request.

Spore viability assay by ether killing

Diploid cells were grown on a YPG plate (YEP+ 2% glycerol). After 24 hours, the cells were transferred to a YPD plate. After another 24 hours, cells were transferred on to a SpoVB plate and incubated for 48 hours. Cells were then replica plated onto a large glass plate containing YPD + 0.1M (NH4)2SO4. Thick filter paper (Whatman 2MM) was soaked in ether and placed on the inner part of the lid of the glass plate. The lid was put on top of the plate and plates were kept in a closed chamber, containing a beaker filled with ether, for 40 minutes, with the filter paper being re-soaked in ether after 20 minutes. Lids and filter paper were then removed from the plates and plates were allowed to air dry in the fume hood for 1 h. Plates were then incubated at 30 °C for 14–18 h until spore viability could be assayed.

Immunostaining

Monoclonal rat anti–α-tubulin (1:500; AbD Serotec) and rabbit anti-Cdc14 antibody (SC-33628; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), Secondary antibodies, pre-absorbed against sera from other species used in labeling were conjugated with Cy3 (Millipore) or Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) and diluted 1:500 (Cy3 and Alexa Fluor 488). DNA was visualized by staining with DAPI.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Kerr, G. W. et al. PP2ACdc55’s role in reductional chromosome segregation during achiasmate meiosis in budding yeast is independent of its FEAR function. Sci. Rep. 6, 30397; doi: 10.1038/srep30397 (2016).

References

Petronczki, M., Siomos, M. F. & Nasmyth, K. Un menage a quatre: the molecular biology of chromosome segregation in meiosis. Cell 112, 423–440 (2003).

Kerr, G. W., Sarkar, S. & Arumugam, P. How to halve ploidy: lessons from budding yeast meiosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 3037–3051 (2012).

Toth, A. et al. Functional genomics identifies monopolin: a kinetochore protein required for segregation of homologs during meiosis I. Cell 103, 1155–1168 (2000).

Rabitsch, K. P. et al. Kinetochore recruitment of two nucleolar proteins is required for homolog segregation in meiosis I. Dev. Cell 4, 535–548 (2003).

Petronczki, M. et al. Monopolar attachment of sister kinetochores at meiosis I requires casein kinase 1. Cell 126, 1049–1064 (2006).

Clyne, R. K. et al. Polo-like kinase Cdc5 promotes chiasmata formation and cosegregation of sister centromeres at meiosis I. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 480–485 (2003).

Matos, J. et al. Dbf4-dependent CDC7 kinase links DNA replication to the segregation of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I. Cell 135, 662–678 (2008).

Corbett, K. D. et al. The monopolin complex crosslinks kinetochore components to regulate chromosome-microtubule attachments. Cell 142, 556–567 (2010).

Sarkar, S. et al. Monopolin subunit Csm1 associates with MIND complex to establish monopolar attachment of sister kinetochores at meiosis I. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003610 (2013).

Kerr, G. W. et al. Meiotic nuclear divisions in budding yeast require PP2A(Cdc55)-mediated antagonism of Net1 phosphorylation by Cdk. J. Cell Biol. 193, 1157–1166 (2011).

Bizzari, F. & Marston, A. L. Cdc55 coordinates spindle assembly and chromosome disjunction during meiosis. J. Cell Biol. 193, 1213–1228 (2011).

Queralt, E., Lehane, C., Novak, B. & Uhlmann, F. Downregulation of PP2A(Cdc55) phosphatase by separase initiates mitotic exit in budding yeast. Cell 125, 719–732 (2006).

Keeney, S., Giroux, C. N. & Kleckner, N. Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell 88, 375–384 (1997).

Stegmeier, F., Visintin, R. & Amon, A. Separase, polo kinase, the kinetochore protein Slk19, and Spo12 function in a network that controls Cdc14 localization during early anaphase. Cell 108, 207–220 (2002).

Dawes, I. W. & Hardie, I. D. Selective killing of vegetative cells in sporulated yeast cultures by exposure to diethyl ether. Mol Gen Genet 131, 281–289 (1974).

Rock, J. M. & Amon, A. The FEAR network. Curr. Biol. 19, 1063–1068 (2009).

Stegmeier, F. et al. The replication fork block protein Fob1 functions as a negative regulator of the FEAR network. Curr. Biol. 14, 467–480 (2004).

Tomson, B. N. et al. Regulation of Spo12 phosphorylation and its essential role in the FEAR network. Curr. Biol. 19, 449–460 (2009).

Shou, W. et al. Exit from mitosis is triggered by Tem1-dependent release of the protein phosphatase Cdc14 from nucleolar RENT complex. Cell 97, 233–244 (1999).

Ye, P. et al. Gene function prediction from congruent synthetic lethal interactions in yeast. Mol. Syst. Biol. 1, 2005.0026 (2005).

Carlile, T. M. & Amon, A. Meiosis I is established through division-specific translational control of a cyclin. Cell 133, 280–291 (2008).

Buonomo, S. B. et al. Division of the nucleolus and its release of CDC14 during anaphase of meiosis I depends on separase, SPO12, and SLK19. Dev. Cell 4, 727–739 (2003).

Marston, A. L., Lee, B. H. & Amon, A. The Cdc14 phosphatase and the FEAR network control meiotic spindle disassembly and chromosome segregation. Dev. Cell 4, 711–726 (2003).

Hirose, Y. et al. Chiasmata promote monopolar attachment of sister chromatids and their co-segregation toward the proper pole during meiosis I. PLoS Genet. 7, e1001329 (2011).

Sakuno, T., Tanaka, K., Hauf, S. & Watanabe, Y. Repositioning of aurora B promoted by chiasmata ensures sister chromatid mono-orientation in meiosis I. Dev. Cell 21, 534–545 (2011).

McKee, B. D., Yan, R. & Tsai, J. H. Meiosis in male Drosophila. Spermatogenesis 2, 167–184 (2012).

Koren, R., Rainis, L. & Kleinberger, T. The scaffolding A/Tpd3 subunit and high phosphatase activity are dispensable for Cdc55 function in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae spindle checkpoint and in cytokinesis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48598–48606 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Tamar Kleinberger, Raymond Deshaies, Kim Nasmyth and Angelika Amon for strains and plasmids. We would like to thank Mark Petronczki for advice and discussions and the anonymous referee for suggestions to improve the ‘Discussion’. GWK was supported by a PhD studentship from Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) and research in PA’s laboratory was funded by a New Investigator grant from Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/G00353X/1) and presently by Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A-STAR), Singapore.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.A. conceived the experiments. G.W.K., J.H.W. and P.A. conducted experiments. G.W.K. and P.A. analysed the results, wrote and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kerr, G., Wong, J. & Arumugam, P. PP2ACdc55’s role in reductional chromosome segregation during achiasmate meiosis in budding yeast is independent of its FEAR function. Sci Rep 6, 30397 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30397

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30397

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.